Steve Mumford may have taken six trips to Iraq in the past seven years, allowing his art practice to be absorbed by picturing the war there, but while his agenda remains curiously ambiguous, he clearly avoids propaganda. In a style inspired by the 19th century American Realist painters, he treats his subjects, from Iraqi prostitutes to Islamic leaders, U.S. soldiers to jihadist fighters with dignity regardless of their beliefs and dealings, a tactic bound to rile his various subjects, never mind his audience.

War is Mumford’s ostensible subject, but the people he depicts are in limbo, not action, putting the emphasis on their individual characters rather than symbolic identity. The prostitutes are modest and brave, huddling together in their black, one-piece swimsuits isolated at the center of an empty swimming pool; a jihadist pausing to write in a notebook on a rocky hillside commands respect as a thoughtful intellectual. Mumford’s paintings work both sides of the fence, eliciting sympathy for a beautiful U.S. soldier who lost her arm one minute, a male suicide bomber who bids a tearful goodbye the next.

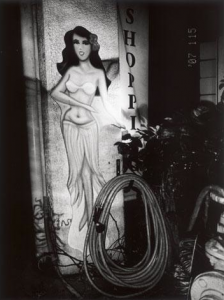

Are terrorists worthy of compassion? Sympathy? Mumford shifts the decision to us, obscuring his point of view by framing the painting in cheesy fake flowers and explosives that diminish its sincerity. Likewise, there’s nothing straightforwardly heroic or the reverse in the appearance of U.S. troops skinny-dipping in a marsh, no uniforms hiding their unique complexions, builds and tattoos. Small text paintings inspired by bathroom graffiti in military camps round out the show, trafficking in disillusioned cliché and acting as foil to the nuances of the portraits that spare judgment and replace dogma with real people.

Originally published in Time Out New York, no 755, March 18-24, 2010.