It says something when an artist can produce an exhibition of totally abstract artwork that runs the risk of being too obvious, but Trisha Donnelly’s latest solo show is almost unsettlingly easy to read. With no gallery statement and only one titled work, a few things are still left up in the air, but this show’s layout and content make for a pleasant, if straightforward, journey through the artist’s thought process.

A kidney-shaped desk (a found object) titled The Secretary, which greets visitors in front, seems at first uncomfortably obtuse, blocking access while posing the question of what we’re meant to glean from it. Only in the next room do its feminine curves make sense in comparison with a pretty pink marble sculpture, adorned with concave impressions that evoke breasts or eyes and appear to channel Brancusi. It seems we’ve stumbled on the secretary herself, a surprisingly primal creature, minimally altered from her natural state but with striking features nonetheless.

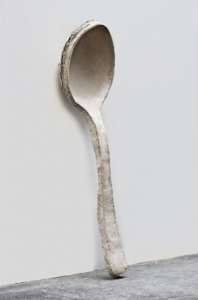

Such amusing opportunities for personification eventually peter out as Donnelly, who used a rotary saw to incise columnar and grille-like shapes into two sculptures, settles for the traditional role of mason. This suggests that while her contemporaries are content to dig into modernist history, Donnelly goes further back in time, mining raw material from the same earth as the ancients (the pieces are made out of limestone quarried in Bolzano, Italy). She calls to mind their labors while producing forms that resonate with contemporary life.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 769, June 24 – 30, 2010.