For ‘Flash Art’ Magazine

‘New Wave,’ a group show curated by Franklin Sirmans, inaugurated Kravets/Wehby’s new gallery space last December. Still located on the same block of 21st Street in Chelsea, the formerly closet-like space has given way to a gallery big enough to accommodate large paintings by emerging artist Kehinde Wiley and expansive work on paper by William Cordova. Five other young artists with an urban sensibility rounded off what seemed like a mini-spin off of Sirman’s popular ‘One Planet Under a Groove’ exhibition at the Bronx Museum last year. Paying homage to an influential exhibition at PS1 in 1981, the show presented artwork indebted to hip hop music and culture with a focus on portraits. Iona Brown’s painting on a Japanese screen of a half Asian, half African woman with Louis Vuitton logos stamped across her skin complimented Kehinde Wiley’s painting of young man nearly swallowed up by his over inflated puffer jacket. Jeff Sonhouse painted two sharply dressed men whose faces, clothing and hair were created out of burnt matchsticks. Sanford Biggers altered an old army recruitment sign, one of the first to feature an African-American man, to read as a statement of inclusion and exclusion, while pieces by William Cordova and Luis Gispert speak to a fascination with boomboxes and turntables, the instruments of DJ culture. Set to the beat of a sound installation by DL Language/Josh Taylor, the exhibition smartly mixed admiration of and critique of hip hop culture.

Jay Davis, at Mary Boone

For ‘Flash Art’ Magazine

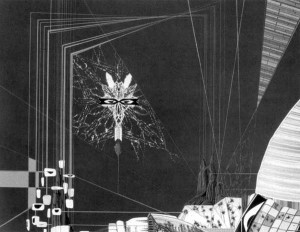

Photons blast into a menacing blob, a rock monster stalks his terrain, and two otherworldly demigods, only their faces visible, square off in a bloody battle. Turmoil has engulfed the Galactic Republic in six new paintings with Davis’ signature blend of hard edge abstraction and sci-fi menace. Davis’ abstract patterns are so dynamic that they lend themselves to a narrative, aided by the painting’s suggestive titles and the recognizable, figurative elements.

In ‘I Think It’s Time to Leave,’ a goofy looking figure of a goat’s head with blindfolded, gem shaped eyes and a flame coming out from under his chin seems to blast off from a ground composed of various geometric patterns. Splatterings of blood red paint dot the patterns, suggesting violence even if it’s not obvious what might have happened. This painting, with its clear differentiation between ground and sky, is one of the few that connects these paintings to Davis’ early work. ‘Who’s Asking Questions,’ on the other hand, enters a whole new dimension of space, with a mirrored ‘v’ shape dividing the canvas between top and bottom. A mask-like face dominates each sphere. Above, an indistinct, oval shaped face, outlined in wavy blue and red lines and framed by what looks like bloody gashes, peers down at a second visage, this one with distinct features composed of clear lines.

It’s unclear why these Janus faces are locked in confrontation, but this feeling of conflict comes across in nearly all of the new work. It’s a fight that seems to extend to the composition of the paintings themselves. As if from the tightly controlled blocks of seemingly random patterning, the creatures have managed to wrench themselves free, allowing abstraction and representation to go to war against each other. Under the spidery trace of a psychedelic, tie-died snowflake pattern that appears in some variation at least once in every painting, Davis expands to a cosmic stage where the fundamental oppositions of painting can battle it out alongside other masters of the universe.

Eddo Stern, at Postmasters

For ‘Tema Celeste’ magazine

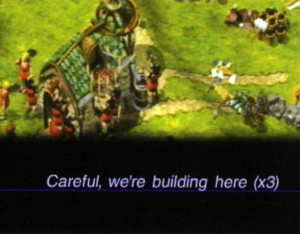

In a unique spin on being “true to the medium,” Eddo Stern appropriates clips from violent video games to reconstruct historical events. For his first New York show, the Israel-born artist presented the video Sheik Attack, a history of Israeli military attacks on Palestinian leaders during the 1990s. In the back gallery, Stern pulled together a mini-exhibition of Afghan war rugs decorated with images of weaponry used in the fighting between the Mujahideen and the Soviets during the 1980s.

Sheik Attack begins in 1966 with an army of little men and women from a simulation game building a house to the upbeat sounds of a nationalist 1960s Israeli folk song. The video cuts to 1999 and a view of an unending metropolis created with the computer game SimCity. Later, nighttime commando raids, sampled from games like Command and Conquer and Nuclear Strike, are contrasted with an Israeli pop song about a peaceful night of rest and dreams. In the second gallery, handwoven Afghan rugs from the ’80s and ’90s lined the wall. At first glance, they appeared to be decorated with traditional abstract and floral patterns, but on closer inspection the decorative elements turned out to be precise renderings of helicopters, AK-47s and hand grenades. Sheik Attack has been described by the curator as a video “woven” from various inspirations, suggesting a parallel between his vernacular medium and that of the rug makers. The weapons on the rugs bear a striking similarity to some of the low resolution digital video images in his work. And now that the Israeli military’s attacks on the leaders of Palestinian political groups are front page news again, the work has even more relevance. Stern’s use of video game imagery implicates viewers, who are usually the active agents in the game, drawing us into the Middle East conflict in a highly personal way.

Painting as Paradox, at Artists Space

For ‘Flash Art’ magazine

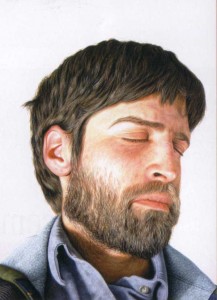

Since its supposed rebirth in the past decade, painting has been the subject of international exhibitions, books and magazine articles. Last fall, ‘Painting as Paradox’ at Artists Space took its own look at the genre in an exhibition of work, hung salon style, by over sixty emerging artists. Hanging on the wall at the entrance to the show, ‘Minotaur 1.1,’ a labyrinth constructed of gilded picture frame by Jan Baracz, alluded to the multiple paths available to the artist without employing an ounce of paint. It also introduced the ‘paradox’ of the artist who still manages to work in what has been called a ‘dead’ or underrated medium. The show’s main proposition was that painters are avoiding dead ends and make the medium relevant to contemporary art and life by embracing the influence of photography, architectural images and computer ‘painting’ software.

One long wall devoted almost exclusively to photographically influenced realist portraiture included Octavius Neveaux’s black and white self-portrait that mimicked the act of looking into the camera, and Isca Greenfield-Sanders’ sunbather, painted from composite photos. A wall of landscapes favored abstract compositions like Millree Hughes’ light infused lenticular prints and Odili Donald Odita’s angled horizontal planes painted on canvas. In a separate room devoted to architecture as subject matter, Carla Klein and Marc Handelman each presented foreboding futuristic interior spaces, that contrasted with the kitschy Miami Vice vibe of Australian painter Kieren Kinney’s hand painted island cityscape at night that resembled a computer generated image. Several paintings adopted a mechanical look, and several digital prints affected the look of painting, like Claire Corey’s complex skeins of looping color. Artists even used video to ponder the concerns of abstraction, like Robert Bermejo’s software program generating patterns on a flat screen monitor and Perry Hall’s DVD of paint, bubbling like lava.

The conceptual framework of “Painting as Paradox” was built on the understanding that painting is still not entire out of trouble. By focusing so heavily on paintings that adopt elements of digital technique, the show implied that the genre needs to ‘do something’ to make itself more relevant to those who would dismiss it in favor of new media. This point of view isn’t surprising given curator Lauri Firstenberg’s own tastes and respectable track record, both of which tend toward exhibitions of photography and architecturally inspired artwork. But this organizational principle doesn’t do justice to the wide range of painting being made today. A more concise exhibition that clearly stated its biases could have avoided a true paradox, which is that the tired discussion of painting’s health continues to occupy center stage in art discourse.

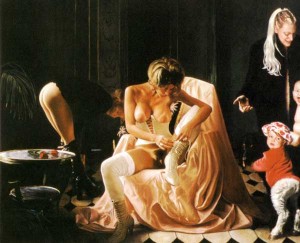

Regarding Gloria, at White Columns

For ‘Flash Art’ Magazine

A mini wave of exhibitions focusing on feminist art and its present day legacy hit New York last fall. White Columns led the way with two shows: ‘Gloria,’ which featured feminist art from the 70s, followed by a modern day sequel, ‘Regarding Gloria’, that tried to gauge the impact of feminist art on contemporary women artists. From over 1000 responses received in an open call for submissions, the curators chose work by ten young women artists who reinterpreted the old slogan ‘the personal is political.’ For example, MK Guth’s DVD, in which she plays a caped superhero was reminiscent of Dara Birnbaum’s 1978 images of Wonder Woman. But in her humorous narrative, Guth’s valiant deeds not only critique the usually male superhero persona, but also act out a fantasy of empowerment. Likewise, Jenny Holzer’s statements to the general public contrast Kathleen Kranack’s highly personal list of the comments and insults she has received from men. Shocks like Carolee Schneeman’s 1975 performance, during which she pulled a scroll from her vagina, weren’t replicated in ‘Regarding Gloria.’ Instead, several artists crafted slick displays or featured the bodies of other women, to comment on the ways in which women can be complacent in their own oppression. For instance, one of Cheryl Yun’s fashionable handbags featured tiled images of a woman’s Botoxed face, Melissa Potter’s ‘Price Per Fuck’ series paired photos of luxury items with a calculation of the price for the sexual favors which secured these gifts, and Edythe Wright’s deconstructed Wonderbra was pinned in a glass case like an exhibit at a natural history museum. Thirty years after feminism’s heyday, women still challenge sexism and assumptions about the ‘ideal’ woman, but ‘Regarding Gloria’ suggests that they now do so with less urgency and more humor.