For ‘Time Out’ Magazine

As the title of L.A. sculptor Evan Holloway’s New York solo debut, “$ocial epi$temology,” suggests, the artist is known for two things: formal whimsy and theoretical sources. This show of seven sculptures makes good on the former, but hits a snag when works fail to do more than turn postulates into punchlines.

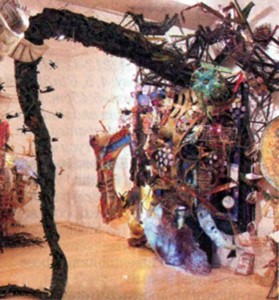

Several sculptures refer to scientific or social principles, but eschew complexity for humorous effect. Second Law,” a spindly metal wheel poised over a plaster box studded with batteries, illustrates a Newtonian law of motion: An object will change velocity if pushed. Visitors are invited to spin the wheel as if they were playing a game on the midway. The show takes its satirically heady title from a tower of multicolored, clownlike heads with Rudolph-style bulbs in place of noses – a carnivalesque spectacle that sheds little light, blinking or otherwise, on the social significance of knowledge.

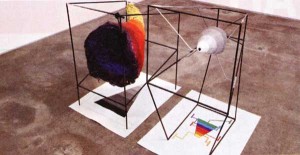

The number of one-liners here makes you wonder if these are the strongest examples of the artist’s work (some viewers may fondly recall the subtler objects included in the 2002 Whitney Biennial). One happy exception is the diagrammatic “Asymmetry Demonstration,” which pairs a large, colorful cornucopia with a smaller black-and-white cone, each suspended in its own metal frame and resting on a chartlike drawing. A better illustration of the artist’s caprice than any intricate system, it reminds us that beauty and a way with materials are the bedrock of art.