For Gallery 210 of the University of Missouri, St Louis

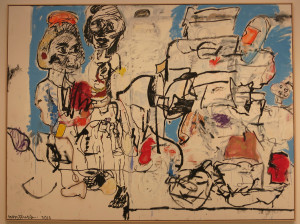

Shopping the Cheryl Yun Collection starts out fun but has a big catch. Apart from the fact that its stylish handbags, lingerie and swimwear look as though they belong in a high-end boutique but are meticulously crafted in delicate-looking paper, the subject matter is shocking. When curious ‘shoppers’ inspect the enticing goods more carefully, the kaleidoscopic patterning on each item turns out to be an abstracted image of war, natural disaster or another horrific event, setting up a bait and switch game that delivers not shopping pleasure but a jarring reminder of the coexistence of enjoyment and suffering. By implicating her audience’s desires as consumers and forcing a personal response to international events beyond the control of any individual, Yun’s faux fashion line shatters the status quo of daily life.

From the materials she uses to the themes she explores, constant contradictions force provocative connections where none were first apparent. Purses, underwear and the whole shopping experience itself is a decidedly female domain, but the images that adorn these objects refer to the traditionally male territory of war and politics. Sexy underthings may in themselves symbolize the dynamics of attraction between men and women, but these take the discussion about power relations to a new level. The gap between images of terror and female accessories would seem even harder to bridge, but Yun, who lived in New York at the time of the 9/11 terrorist attack, readily recalls former Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s highly publicized suggestion that the best way to recover (and save the local economy from further damage) was to “go shopping.”

At the time, it may have been an exercise in civic duty to hit the stores, but with consumer spending making up the largest part of our GDP, Americans hardly need any extra incentives to shop. Yun’s project, whether replicating high-end clothing or the cheapest plastic shopping sacks, provokes questions about our appetite not just for things but for entertainment. “We consume imagery like we consume objects,” Yun explains. “Sitting down with the newspaper and a cup of coffee is a pleasure that many people, including me, enjoy, but actually involves reading about horrible things happening around the world.” Yun’s garments are not only intimate but force their imaginary owners to literally wear images of far away events next their skin suggesting false familiarity; like Yinka Shonibare’s Victorian costumes fashioned from traditional African fabrics, they reveal the ignorance at the core of cultural imperialism.

Yun is the first to admit her own role as consumer. Afterall, each bag or garment begins with a news photo from the New York Times or an Internet news source that caught her eye for its drama, compositional qualities or captivating story. To create a ‘fabric,’ she scans, manipulates and prints the image, carefully piecing multiple copies together into a seamless pattern. Early bags unambiguously reproduced disturbing news photos; the more recent series are less confrontational, dabbling in the potential beauty of particular forms, multiplied and mirrored with an abstract effect. But disguising the source image and adorning each item with delicate details, like smocking or tiny bows, makes it all the more chilling when a diving figure on a swimsuit materializes as a toppling statue of Saddam Hussein or it becomes clear that a lace pattern originated in an image of an explosion.

The title of each piece (always derived from the source newspaper’s image caption) helps give the game away by leading viewers to try to make out the original image and ensuring that provocation, though it may have grown less obvious, stays at the heart of Yun’s project. At its conception, CY Collection took as its vehicle what Yun calls “…the extreme commodity. If you’re going to buy just one thing, it’s going to be a handbag.” Fittingly, when her conceptual enterprise diversified to carry lingerie and swimwear, these items represented two other extremes: of femininity and of ideological martyrdom. Fascinated by stories of female suicide bombers, Yun researched the practicalities of concealing a weapon for attack. The resulting lingerie and swimwear morphs a purely utilitarian device for strapping on explosives with hidden support garments, resulting in a ramped up garment for traditional seduction and destructive power.

Since it was agreed in the 60s that the personal is political, conversation about sexuality and power have been closely linked. A garment like ‘Flyaway Babydoll with Suicide Hipsters I,’ (2005) decorated with pictures of flag bearing U.S. troops recalls the age-old appeal of a man in uniform to the girls back home (or in every port). But its source image – a photo from President Bush’s highly staged 2005 landing on an aircraft carrier –recalls how a celebration of bravado has become an impotent gesture in light of political instability in Iraq. One of Yun’s most striking pieces is also one of her most daring designs: ‘Halter Teddy with Suicide Belt’ (2004/05) features a text in Arabic behind a gunman and his kidnapped victim reproduced to make a beautiful, calligraphic pattern on the garment’s breast and hip area. Literally embodying opposite excesses of Western immodesty and of Islamic fundamentalism, the garment is itself embodies conflicting extremes.

Though contrast is central to Yun’s work, it is never crass. While artists like Thomas Hirschorn have notoriously appropriated unpublished images of the U.S. war in Iraq from the Internet, these displays are calculated purely to shock by their graphic depictions of brutality. Using images from major publications forces Yun to operate within their calculated standards of decorum, a decision that allows her imagery to be more than just alarming. Her work echoes the punch of Barbara Kruger’s cynical assertion, ‘I Shop, Therefore I Am’ or Jenny Holzer’s self-conscious plea to ‘Protect me from what I want.’ But Yun eschews an anonymous production style, instead offering abundant evidence of her own hand, whether it’s in CY Collection’s obviously hand drawn logo or an awkward length of cording on an individual garment. The approach keeps her project personal, giving credence to her claim that she’s exploring conflicts that she herself faces. That keeps us on her side as she brings a critique of consumer culture into the present day climate of anxiety – one in which images of far away disaster could suddenly loom much closer.