Image credit: © P.A.R. Photo by Marc Domage

Picasso may be one of the 20th century’s most influential artists, but the jury is still out on the value of his late works. ‘Mosqueteros,’ an exhibition of nearly one hundred paintings and etchings at Chelsea’s Gagosian Gallery is the first major U.S. effort since a 1984 Guggenheim show to change the prevailing perception that the late master had lost his touch by the time of his death at age 91 in 1973.

In a great blast of energy, Picasso spent the final years of his life creating hundreds of paintings after canonical works by Velasquez, Goya, Delacroix and other old masters. Adapting images of soldiers, prostitutes and performers to his trademark, fragmented and twisted style, Picasso seemed to be grappling with his own position in art history. At the same time, the works’ title, ‘Mosqueteros,’ or musketeers, referred to the non-paying rabble at the theater and hinted at the artist’s status as an onlooker as contemporary art rejected abstraction.

Response to the Guggenheim show was underwhelming. New York Times critic Michael Brenson praised Picasso’s energy more than the work itself, while the less gracious Robert Hughes opined that the work showed only fragments of Picasso’s talent.

So why try to change the record now? John Richardson, curator of this show and Picasso’s biographer, says he’s ‘avenging’ Picasso of the poor response to his work; more interesting to a contemporary art audience, he also explains that he intends the artist to, “…look like a brand new painter.”

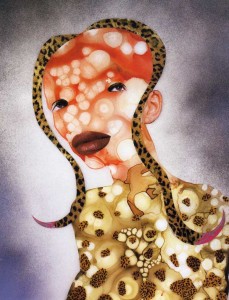

Portraits like Buste (1970), a character whose feline face is created with pools of dark paint punctuated by a phallic or key-like orange monocle, immediately make the case for Picasso as a forerunner (albeit distant and far more dignified) to young, expressionist-inspired artists like Jonathan Meese and Andre Butzer. Though the character’s terrible, black-eyed gaze ties him to Picasso’s other harrowing portraits, Picasso eschews the sketchy outlines he uses in many of the show’s other works, and composes using blocks of color in a style that enhances the mystery of his shadowy personality.

In 1984, Hughes noted the speed with which Picasso painted, and condemned the artist for making his painting process more important than the final product. Nowadays, that’s accepted practice in any media, from Josh Smith’s paintings, to Fia Backstrom’s performance/installation work to Walead Beshty’s photography and sculpture.

Picasso’s late paintings aren’t likely to be direct precedent for any of these artists. But given the popularity of mining 20th century avant-garde art history (think camera-less photography, constructivism, 60s and 70s performance), it’s fascinating to see evidence of the reverse process – a canonical artist who seems to have deliberately pointed several ways forward. As evidence that he was a wellspring of ideas until the end, this exhibition will doubtless have the legacy-effecting impact it deserves.