The sense of expectation was huge. In the first issue of Artforum published after the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, the first sentence of the first article read, “In the days following September 11, it was agreed upon by just about everyone that art, along with everything else, was going to ‘change forever.’” Two and a half years later, nothing as obvious as a revolution towards the political has come about. Instead, the way we look at art has changed. Aware of political events in which we have a direct stake, we look for corroborating references in artwork. At the same time, there is a growing consensus among U.S. critics and curators that there is a resurgence of craftsmanship and the handmade, a widespread interest in art and culture of the 60s and 70s and a tendency amongst artists to create fantastical worlds of their own.

Recognizing these trends in an article on young art dealers, a New York Times reporter recently observed that, “Nobody is protesting anything.” Lack of protest doesn’t automatically disconnect art from politics, however. This article samples from the recent work of three young artists who are making waves with artwork that explores the consequences of American politics at home and overseas. Aaron Spangler’s woodcuts of anarchic Midwestern communities are a vision of American ‘can do’ spirit gone horribly wrong. On the international front, several artists have traveled to Baghdad before and after the war, including Paul Chan. His DVD ‘Happiness’ makes no illusion to the Middle East, but is highly relevant to the topic of war. In her latest five-screen installation, showing in the current Whitney Biennial, Catherine Sullivan responded to a terror attack that took place on the other side of the world, but which she nevertheless felt personally.

Anarchy in the U.S.A.

On Aaron Spangler’s studio wall hangs a photograph of a young man with long thin hair grasping a megaphone and shouting for all he’s worth. The picture depicts a younger Spangler and the occasion is his war, that is, one that he planned and staged with a friend at college. Since he was a child, the Brooklyn-based, Minnesota native has been fascinated by war’s devastation and its potential as a metaphor for psychological conflict. However, while the U.S. is obsessed with terrorism in its cities and abroad, Spangler focuses on anarchy in rural America in large woodcarvings of battle ravaged landscapes.

Blowing apart the stereotype of the quiet farming community, Spangler carves hellish scenes set in the Midwest. In ‘Mercenary Battalions’, a 7 x 3 ½ foot panel, a helicopter hauls an old wooden farmhouse into the air, centuries-old trees topple to the ground and an electrical tower lies on its side to act as a makeshift bridge over a river filled with debris. Similarly, ‘The Revelers’ is an apocalyptic account of a town’s destruction seen from the main street. The buildings that have not been bombed out are being used as bars and meeting places, their awnings painted with anarchy symbols, pentagrams and upside down crosses. Directly overhead, a bomber drops its payload, intent on wiping out whoever has occupied the once tranquil burg.

With rebellious zeal worthy of an adolescent, Spangler reverses the social order of small town America – damaging it physically and disrupting the prevailing morality. ‘Revelers’ and ‘Battalions’ are so given over to chaos, that you’d think the artist delighted in the idea of wiping out his roots. The opposite is true. In fact, Spangler feels an allegiance to country life and culture that is virtually unknown in the cities, an idea elaborated on in the monumental drawing, ‘The Poachers,’ which depicts rural citizens reclaiming land from the government and big business. They are ‘poaching’ from the powers that be by planting crops and trees and by pulling down the huge electrical towers that cut through their farmland and increase cancer rates. This resurgence of self-reliant, pioneer spirit, likely as it is to be crushed, belies notions of the peaceful heartland evoked by politicians. Spangler’s scenarios are a mix of utopian, anarchic freedom and hellish destruction, American ‘can do’ mentality and radical anti-social insurgence. They’re dark and pessimistic, despite their irony, but ultimately envision a fascinating and frightening revolution against passive consumerism ‘of the people, by the people’.

Trouble in Paradise

Paul Chan keeps his art and politics separate. His consequent double life leads him back and forth between the roles of artist and activist. Case in point – when he traveled to Baghdad last year, he went not to produce his own work, but as a volunteer for the peace organization ‘Voices in the Wilderness.’ Nevertheless, the trip impacted Chan’s artwork, making it, as he explains, more extreme. When he returned to New York, he finished the DVD ‘Happiness (finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization’ which was so well received in a group show at Greene Naftali Gallery that a still from the DVD landed on the front page of the New York Times arts section.

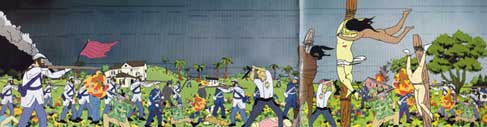

‘Happiness,’ more than Chan’s previous moving image and graphic work, is politicized rather than political. The 18 minute animation tells the story of a community of pre-teen hermaphrodites who live in harmony, suffer an invasion, and then wipe out their oppressors. The protagonists are direct relations to outsider artist Henry Darger’s Vivian girls, while their lifestyle is modeled on the ideas of 19th century ‘outsider’ philosopher Charles Fourier. Following their passions, they loll about in flower-filled meadows with piles of books, enjoying each other’s bodies and their own as they laugh, run and play. Soon, men in suits and army uniforms disrupt the tranquility. Their houses burn and the girls are brutally murdered by a host of men in the guise of various authority figures. As brutalities are inflicted on their helpless bodies, a mysterious wind begins to blow. Just as suddenly as the invasion began, it is over; the men lie dead and dying on the ground as the girls run free again.

In ‘The Communist Manifesto’, Marx and Engels briefly discuss the Utopian Socialists, including Fourier, commending them for their willingness to “…attack every principle of existing society.” Chan combines Fourier’s method of radically rethinking social structure with Darger’s outlandish band of heroines to introduce us to a land far removed from our own. Viewers may not relate to the girls’ utterly abandoned lifestyles – wild to the point of eating flowers and relieving themselves like animals in the fields. But we’re asked to imagine abandoning our inhibitions and letting our passions lead us to fight against injustice. We don’t know how the girls recover their autonomy, but Chan’s insistence on dreaming of a better life is clear. “Utopia is a proxy that stands in lieu of absolute freedom,” he has explained, “…to imagine what this looks like is…an exercise in hope.”

Theater of War

Audiences are well advised to take a deep breath before trying to unravel the series of references that lead from Catherine Sullivan’s inspirations to her finished artwork. Sullivan, an L.A.-based artist whose work usually inspires confused admiration from critics, merges performance with visual art in film installations of alarming complexity. Her most recent production, ‘The Ice Floes of Franz Joseph Land’ results from a trail of references that begins with the hostage drama in October 2002, when Chechnyan rebels took over a Moscow theater. Storming the building in mid-performance, they not only captured the audience but interrupted the simulated reality of the musical with a terrible drama of their own.

When it was overtaken, the theater was performing ‘Nordost’ a production adapted from a novel featuring the long suffering lovers Sanya and Katya. Their story is transplanted to the time-warped ambiance of Chicago’s Polish Army Veterans Association, where most filming took place. This building’s ballroom, small bar area and offices provided Sullivan’s cast of 25 with idiosyncratically decorated spaces in which to enact five pantomimes from each of the novel’s ten sections. Each actor learned all of the parts, so a motion performed by a row of women representing Katya at different points in her life is, for example, performed at other times by male and female actors in a variety of costumes. At the same time, odd characters, like two stony-faced pilots who put on masks, refer to the actual events that took place in Moscow.

Sullivan invests ‘Ice Floes’ with many more layers of meaning than most viewers will ever realize, particularly if they only watch the piece without reading about it. The disconnect between what is seen and what Sullivan means to communicate would be a problem if we didn’t realize that this probably occurs with most art that we see. Although the installation is overwhelming, with actors constantly swapping roles and costumes and action happening on five screens simultaneously, what we do see references the conventions of old Soviet and American film enough to capture the imagination. Most vignettes, particularly those in which only a few actors are involved, are staged and acted in a way that entices viewers to stay and try to figure out the meaning. Of course, a search for narrative will be frustrated. But what may remain is the memory of how Sullivan marshals acting conventions and snippets of action to consider the Moscow siege without making it into another story, burdened with its own point of view. Sullivan doesn’t seem to want her viewers to ‘understand’ ‘Ice Floes’ but somehow, this doesn’t make it any less tempting to try. Instead, the artist correlates confusion in the art gallery with the confused and tragic events of the real world.