Extreme Makeovers

Wangechi Mutu creates collages of fantastical creatures, beautiful but damaged.Her studio was just as I expected: body parts littered everywhere, a tray full of lips on the table, a pair of sleek legs in strappy heels affixed to the wall. In the telling, Wangechi Mutu’s workspace at The Studio Museum in Harlem, where she is a resident artist, sounds like a campy crime scene. In fact, it is a sort of laboratory in which she uses collage and drawing on paper and Mylar to inscribe real crime stories onto hybrid bodies. “Females carry the marks, language and nuances of their culture more than the male,” says Mutu. “Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.” This includes everything from the violence perpetrated against innocent civilians in war zones to the ‘modifications’ made in order to follow fashion.

Artists from Cindy Sherman to Orlan have explored the chameleon-like nature of female bodies for decades. So what makes Mutu’s work unique? Apart from being skilled in montage she coherently refers to race, politics, fashion, and African identity in portraits that pack an aesthetic punch. This cocktail of influences strongly recalls Weimar artist Hannah Hoch’s collages of African artifacts and European bodies in her portrait series, ‘From an Ethnographic Museum.’ But Hoch’s montages beg the question, like ethnography itself, of whether her then-colonial subjects themselves are represented as they think they are or in a manner that reflects Hoch’s view of them. Eighty years later, an artist who was raised in Kenya and has traveled and lived overseas ever since, gives an answer as complex as her experience.

After completing her MFA at Yale in 2000, Mutu found herself in New York without the school’s resources and faced with a crisis of direction. With pen and paper as her chief art supplies, she created the ‘Pin Up Series’ (2001), which established her interest in adaptable female bodies. In two grids of twelve small images, topless women preen and posture for the viewer like calendar girls. “I wanted you to walk up to them assuming you were going to see these pretty, interestingly posed females,” explains Mutu. “It takes people some time to see that every single one of them has some trauma or alteration that is severe and aggressive.” The women, who strike come-hither poses, are amputees. The series was inspired by violence in Sierra Leone, where an illegal diamond trade fueled fighting that maimed many civilians - in effect, trading one person’s well-being for another’s beauty.

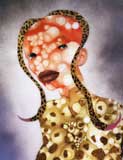

Ironically, the more severe the violence done to her subjects, the more attractive they become, until their flesh, mottled with colored blotches produced by trauma, is as decorative as it is damaged. In ‘Riding Death in My Sleep’ (2002) a bald woman with bloodshot, Asian eyes and huge red lips crouches in a field of mushrooms, her beautiful orange, red and black skin resembling that of a poisonous snake. Mutu graphs animal or mechanical body parts onto other characters, such as two figures in ‘Intertwined’ (2003), from the ‘Creatures’ series. The scantily clad women have the heads of hyenas, animals whose name is an extremely derogative slang term for women in the Swahili language. In other collages, the figures adopt mechanical prosthesis, with several motorbikes becoming a foot, for instance, or joining together to be worn in a shoulder pad arrangement.

For all their mutations and injuries, Mutu’s characters come across as empowered. Using the body language of fashion divas, they simultaneously play the roles of victim and aggressor, adapting to the harm inflicted on them by whatever means necessary. ‘Centipede’ – a series of site-specific wall drawings accompanied by racially-charged texts that appeared in several New York group shows last season - best conveys Mutu’s intentions for her audience. “The point is to get people to access their own position, to enjoy and work at understanding what role they have to play,” she says of her hybrid, exploding insects, which represent the destructive creature foretold by African soothsayers before the arrival of European colonial powers. We are attracted, repelled, and implicated all at once by Mutu’s solitary survivors who remind us that the past is both behind us and looming ahead.