For ‘Art on Paper’ Magazine

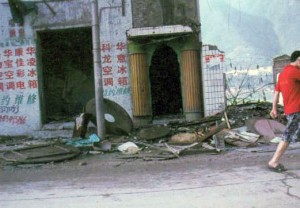

- Allen Ruppersberg, The Singing Posters, 2003. Installation at Rice University Art Gallery, c. 2004 Hester and Hardaway. Photo by Paul Hester (detail)

At sixty-three, Allen Ruppersberg, the thoughtful maverick whose work has returned again and again to posters and books, is finally getting his due.

Today collectors are hunting for underappreciated talent – value-investing, you might say – while young artists with an apathy or a disdain for the machinations of the gallery system are looking for less market-friendly role models. Both may, in part, explain the increasing interest in Allen Ruppersberg, the Los Angeles and New York-based artist whose work was recently the subject of a survey in Europe and was brandished on the March cover of Artforum magazine. Ruppersberg’s cross-disciplinary approach, his embrace of pulp fiction, film, and quotidian graphics, and clever recycling of his old art for new have defined an innovate career that is still unfolding. Of particular interest, especially to artists, is his ongoing use of both posters and books, formats that remain excluded from the art historical canon.

From the early days of his career, Ruppersberg pushed the boundaries of what art could be. In 1969, two years after graduating from the Chouinard Institute in Los Angeles, he established a short-lived cafe in which he served plate-size helpings of environmental art, followed by a similarly short-lived hotel/art installation. By the early 1970s, his love of literature began to manifest itself in artworks based on books, which, since then, have taken many forms, among them text-paintings, installations, and public art projects. In the early 1980s, he hit on the idea of making artwork that mimicked the highly commercial, colorful advertising placards ubiquitous in L.A. at the time.

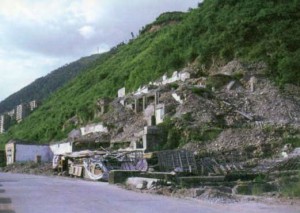

Ruppersberg has a vast collection of postcards, books, movie posters, films, magazines, ephemera and other pop culture artifacts that he uses as a resource for his work. Speaking about the time the artist spent in New York (from the mid-80s through the 90s), Christine Burgin, a New York dealer who has worked with him since the late 1980s, recalls, “Al came to New York and collected CBGB and Mud Club posters, archiving them as if they were fine art.” Burgin adds that in his artwork, “he uses posters of his own making – along with leftovers from jobs printed by other clients of the company that prints them – to disavow authorship, presenting them as they exist in the world.” ‘The New Five Foot Shelf’ (2001), a major installation by the artist, includes a fifty-volume publication with texts written or collected by the artist, and forty-four poster scale ink jet prints that document—photographically—the interior of his old library-like Manhattan studio.

‘The Novel That Writes Itself,’ an epic work that is ongoing, has to be the crowning poster project of his career. Although originally intended to be realized in another form—Ruppersberg sold roles in an autobiographical novel back in 1978 but the project languished before being reborn in poster form – it now consists, in Ruppersberg’s estimation, of more than 800 posters. These include the pages with ads, duplicates, and his own text. More posters are produced each time the piece is installed. Displayed floor to ceiling, the posters have an eye-catching quality while perversely championing a form of communication considered lower than pulp.

In a multi-part work from 2003 and 2005, titled ‘The Singing Posters’, Ruppersberg used this formal precedent to pay homage to a now historical text once deemed obscene: Beat poet Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl.’ The piece consists of a phonetic rewriting of the poem, using changing typefaces, that is printed on nearly two hundred multicolor posters. Whereas most posters are designed to be read at a glance, but these force the viewer to puzzle out the poem, word by word, poster by poster.

Ruppersberg may be reflecting on his own influences in projects like ‘The Singing Posters,’ but others are looking to his example as they find their own artistic voice. Artists like Mark Bradford, Evan Holloway, Scott King, and Carl Pope have all used posters in this work, while other young artists have closer conceptual parallels to Ruppersberg, including Carol Bove’s sculptural installations of books from the 70s, Bernadette Corporation’s cribbing from other people’s works, or North Drive Press’ treasure troves of artist-conceived ephemera.

The new interest doesn’t signal that Ruppersberg has passed the torch, however. He has several new projects afoot, including an installation in June for the Art Unlimited section at Art Basel, for which he is preparing banners (printed by the same company that makes his posters) and thousands of photocopies based on parts of his collection which visitors can take away. There, at the momentary center of the international art world, he will be perfectly positioned to influence and be influenced, to participate in the market and distance himself. “It’s the same dialogue and process of artists talking about common ideas,” he observes, “…but a new generation looks at things differently, and that’s inspiring.”