Jan-Feb 2008.

Sculpture that tries very hard not to look too good. Tobias Buche's deliberately low-grade sculpture conjures a curious portrait of his inner world. Take Merrily Kerr's video tour of this work at Lehmann Maupin Gallery in Chelsea.

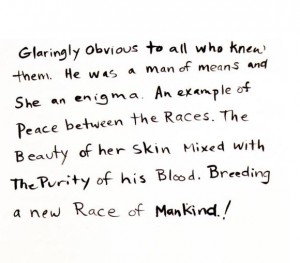

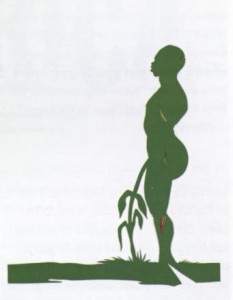

Kara Walker at Sikkema Jenkins

For ‘Art on Paper’ Magazine

By the time Kara Walker’s first full scale American museum survey arrived at the Whitney Museum from the Walker Art Center last fall, a wave of press coverage, including feature articles in the New Yorker and Art in America, made it the must-see show of the season. But it was the fifty-two-panel, handwritten text in Walker’s simultaneous downtown gallery show that deserved the attention. Flanked by smaller works in her signature cut-paper style illustrating atrocities committed against freedmen after the Civil War, the enormous text installation, with an equally expansive title (Search for ideas supporting the Black man as a work of modern art/contemporary painting; a death without end, an an appreciation of the creative spirit of lynch mobs), stood out for its sheer unornamented rawness—no illustrations, just scribbled handwriting—and its scathing references to U.S. military action in the Middle East.

Since the mid-nineties, Walker’s silhouettes, paintings, videos, and projections have consistently conjured imagery of the Old South in abject yet clearly readable scenes of violence and sexual subjugation. When she used text, it was written in what could plausibly be the artist’s own perspective or that of an alter ego. Her more recent text-based work (since 2002) adopts a range of voices—anthropologist, slave, contemporary middle class African-American.

Search for Ideas is an even more cacophonous brew of observations and perspectives. Here, Walker explores the potential analogy between racist attitudes in America and those perpetuated by Americans overseas in texts that refer to Saddam Hussein as a “porch monkey” or Arabs as “sand niggers.” Under the rubric of aggressor and complicit victim, the text details rapes and torture, proffers that black soldiers are willing Klansmen and asks, in the face of global jihad, “how can colored folks get on the winning side w/o giving up their hard-won right to jeans that fit…” Because the fifty-four parts are hung cheek-to-jowl and there is no obvious sequencing, it is unclear whether one is supposed to read them left-to-right, or top-to-bottom.

Likewise, the show’s small cut-paper works and large-scale collages on panels lack clear storylines, such as ReConstruction (2007), a decorative mélange of floating silhouetted heads over a background of post-9/11 New York Times ads offering condolences.

From Richard Serra’s 2005 poster recreating a scene from Abu Ghraib to Jenny Holzer’s presentation of declassified documents pertaining to military bungles in Iraq, among many other examples, Walker is not alone in using her artistic platform to protest U.S. foreign policy. Yet Search for Ideas seems uniquely geared to offend and disturb by its graphic descriptions of violation, its willingness to lay blame all around, and its success at tapping another well of middle-class guilt, this time over atrocities committed in the name of the American public. A schizophrenic toggle between individuals and nations, and between first and third person, makes for a confusing and overwhelmingly despairing indictment. However, as a grating tour de force of ugly truth, the piece is powerfully effective and makes a loud riposte to one text’s assertion that “Knowledge comes in the form of whispers of those in the know.”

News and Commentary: The More Things Change

For ‘Art on Paper’ Magazine

Visitors were in for a surprise at Mary Boone Gallery recently, when the normally frosty atmosphere was melted by the folksy artwork of artist Aleksandra Mir and her team of assistants. Music blared from a boom box, while collectors rubbed shoulders with young hipsters in what looked like an art studio. In a back office, cordoned off but publicly visible, Mir hand-copied onto huge sheets of paper the front pages from hometown tabloids the Post and the Daily News, dating from 1986 to 2000. When she was done, her drawings were transferred to the main gallery where a Sharpie-wielding team of young artists and students diligently filled in her outlines. All in all, some two-hundred drawings from approximately ten thousand front pages were generated.

Mir claimed that she couldn’t care less about the gallery’s newly congenial or keyed down ambience, saying, “That’s the subject that interests me the least. I’m not interested in institutional critique but in having been a citizen of this town.” Yes, it’s true that the project broadcast a fond nostalgia for the city that the Polish born, Sweden-raised artist recently left after a fifteen-year stay. In some the headlines emphasized the entertainment value of the New York tabloids: a ‘Burger Murder’ poisoning was treated with as much import as a ‘Milk War’ waged on grocery prices. In another group, the headlines were linked by money— ‘Killed for a Quarter’ and a $1.5 billion coke bust—highlighting one of the city’s fondest obsessions. Here was a city perpetually enchanted by the same recurring stories; the drawings seemed geared to prove the cliché, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Yet, the high-polish context begged otherwise, revealing instead just how much the art world had changed. The exodus of galleries from SoHo to Chelsea began during the period Mir examined and, in the opinion of many, precipitated a new fashion in art for work made on a scale and volume calculated to fill newly pristine and vast galleries, as well as an unprecedented alignment of real estate and art. By working in the gallery, Mir aimed to emphasize the fact that she never maintained a studio in New York, working instead without the need for one. But the effect was somewhat different, unintentionally acknowledging a situation whereby artists can no longer afford the city’s rents. Mir became the emblematic displaced artist of today, shunned not to the sidelines as in times past, but to center stage, a peripatetic entertainer in a theater of gold.

Mika Rottenberg, Long Hair Lover

For ‘Flash Art’ Magazine

The female body, in all its potential fantastic proportions, obsesses Mika Rottenberg. Her eccentric videos have featured body builders, dancers, wrestlers, and porn models laboring in confined, assembly-line settings to manufacture unusual objects related to the body: fast-growing fingernails morph into cherries, perspiration becomes the scent for tissues, and in the video ‘Dough’ (the highlight of her first New York solo gallery show early in 2006 at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery), the tears of an obese beauty cause dough to rise.

More recently, Rottenberg has abandoned her cramped studio in favor of the wide-open spaces of the natural world. Inspired by the story of the Sutherland Sisters, a 19th century family of girls who displayed their extra long hair in a Barnum & Bailey performance and marketed their own hair growth formula (supposedly including mist collected at Niagara Falls), she worked with members of a present day long hair club to make the short trailer, ‘Chasing Waterfalls: The Rise and Fall of the Amazing Seven Sutherland Sisters (part one).’ As winner of the inaugural Cartier Award, Rottenberg screened the video at the 2006 Frieze Art Fair, giving her audience a tantalizing glimpse of the related project on which she is now working.

MK – Your videos have been set in an enclosed space; now you’re working outdoors. What has that shift been like?

MR – In past pieces like ‘Dough,’ I built one part of the set at a time and worked individually with each actor. I wanted to see what I could do with limited space. Now, I’m interested in finding out what I can do with no spatial limits, so I’m building a set completely from scratch in the middle of the woods.

MK – How did you choose the location for your shoot?

MR – The actors in the trailer are part of a long hair lovers Internet club, and three of them live near one town in Central Florida. I actually wish I could write a sitcom about the RV park/ retirement community where I’m staying. People there have a lot of time on their hands, which makes them creative – they do things like have their own parades. The Boy Scouts are even going to help me behind the scenes. Thanks to a piece in Vanity Fair, I got permission from a local farmer to do whatever I want with a huge piece of land that includes a petting zoo that no one visits.

MK – Has your normal working process had to change?

MR – My process usually follows several distinct stages: I start with drawings, which come purely from my imagination; then I try to find people I want to work with; I build the set or sculptural environment; then work with the actors in the space, making a lot of set changes. Eventually, there are always moments over which I have less control, as when I introduced the dough in ‘Dough.’ There’s gravity and you know it’s going to go down, but I don’t know how a person is going to behave. I try to keep the camera on all the time so I have hours and hours of footage, but often, the material I actually use is from moments when the actors forget the camera is on. My first thought for my current project was to mimic a reality TV show by creating a space – in this case, a functioning 19th century farm – and asking the women to just be there for a week. The scenario, along with their bad acting could really make it ridiculous and funny.

MK – Will there be similarities to your previous themes?

MR – The project is in the beginning stages and could still go in so many directions. But like my other videos, I want the whole story to revolve around cause and effect – presenting a problem and then solving it. It may be a poor farm and the women bad farmers. Something will break and that will trigger the next thing, a method that will promote the story and develop the characters. I’m thinking in an almost sculptural way and trying to have the story be more physical, because I can’t write dialogue!

I’m inspired to think of the farm as a giant Earthwork in the sense that it’s a zone for experimentation with earth. There are parallels between the incredible amount of labor that goes into farming and the routines the women adopt to care for their hair, such as brushing it daily for two hours. I spent this week trying to make a device that would convert the strokes of a hairbrush into an energy source that could power other things on the farm, though I’m not sure I’ll even use the device in the final version.

MK – You closely associate the women with nature, whether it’s being near a waterfall or on a farm.

MR – My videos employ clichés about femininity, and this one involves associations between women, fertility and the earth. I’m attracted to how these trite ways of thinking about women offer a kind of bliss, that is, they satisfy a basic desire for resolution and simplicity. I’m a sucker for the related visual images – girls playing with little lambs and bunnies, waterfalls, and long blond hair blowing in the wind. But the fun really starts when I dissect the clichés, turning them inside out and showing them as they really are – creepy and uncanny.

The Sutherland Sisters started selling their hair fertilizer as a result of the Industrial Revolution. They marketed their product right after chemical fertilizers for the soil came on the market, implying that if you could grow grass that much faster, then you could also grow hair. I like the contrast between male baldness and a super abundance of female hair.

MK – Certain aspects of the trailer remind me of a romance novel or soap opera.

MR – Absolutely, because its about entrepreneurs and new horizons. It blurs the line between cheesy, funny and genuine.

MK – Have you intentionally used humor in your past work?

MR – Whenever I try for it to be funny, it’s probably not, so I don’t. In ‘Dough’ there’s more of an awkward weirdness and element of grotesque that might come across as funny. It actually depended on the reaction of the other people watching the screening; if people were laughing you felt like it was funny whereas if people were serious you felt unease.

MK – That video seems to intentionally subvert conventional notions of beauty. The obese woman is pretty whereas the thin woman’s proportions are grotesque.

MR –I don’t know if I consciously think in terms of beauty or subverting beauty. My interest is more in things that the body produces and the way you use the body and it becomes more like an object. Some long-haired women relate to their hair like it’s a pet. The Sutherland sisters were smart not to cut and sell their hair, but to keep it and use it as an object in their Barnum and Bailey act.

MK – Is your art about society’s response to their extremes?

MR – I don’t think it’s about society’s reaction to long hair or fat people. It’s about society’s interaction with the body in all its possibilities. Of course, there’s a layer that relates to American obesity, but that’s not my focus. Instead, it’s more about taking something to an extreme to examine it. If the dough is a stand-in for the body, there’s a fantasy about the body’s ability to stretch as if there’s nothing inside.

And it’s also more about my personal attraction to long hair or to big bodies, for example. For my video ‘Time and Half’ I’d been looking on the Internet for someone with really long hair and then saw a woman on the subway. In that piece, I manipulated the background (a Chinese takeout restaurant) by adding more palm trees to emphasize how the girl and her hair are so exotic.

MK – Could you be accused of exploiting your characters?

?MR – I’m always waiting for that question. In a way, I am using the actors almost as objects, which is supposed to be a bad thing to do. I’m not trying to be a saint, and I don’t think the artist’s part is to be “the good guy.” I often feel uncomfortable in the position in which I put myself, but my connection with the actors runs like an experiment, a behavioral observation or a motion study. I can see how that can be exploitative, but it’s hard to make work about that without actually doing it. You could argue that we have an equal and satisfying relationship serving each other’s needs as exhibitionist and voyeur.

MK – Does your work come from a feminist perspective?

MR –I’ve always defined myself as a feminist. There is an aspect of misogyny in my work that is a response to the way society in general is. So I have to ask myself what it means to be a “good” feminist. If I use peoples’ bodies and objectify them, then I’m a bad feminist, or I’m promoting the usual stereotypes. But since these are so common in daily life, it’s a way to negotiate or understand them and make them empowering. I keep questioning my own morality.

MK – There’s another –ism that relates to your work. Can you tell me about your references to Marxism?

MR – The very definition of labor is the process between a person and nature, but actually, I’m interested in Marx’s writing in an abstract way, as more poetic than political. The way he describes production and a person in motion is both beautiful and very visual. What’s inspiring to me is his way of measuring units of energy, materials and time involved in labor. Everyone assumes that in ‘Dough’ there is an end product, but in my mind, the rising dough is constantly growing in volume so the excess that is pushed out is really more of a unit that measures work. The process of handling the dough also uses the forces of nature like gravity, allergies and other reactions. In the new video, I’m growing crops and thinking of how to control the animals’ movement by harnessing their desire for food. It’s almost as if they’re the dough.

MK – What do the women in the long hair club think of reconnecting with nature?

MR – They’re each different but are all high maintenance. You have to be when you have hair that long. It gets delicate and they count every hair and split end. Most of the time it’s up, but when they take it down, it’s like a ceremony and their mobility can be almost paralyzed. But each has a unique relationship to her hair, and unlike my past videos only one of them makes a living (running a soft-porn website) from her unique feature. Very long hair is attractive to a lot of guys, but the women distinguish between the fetishists and the long-hair lovers. If they meet a man, he has to pass tests to make sure the attraction isn’t sexual, although, of course, it’s sexy.

MK – This sounds like a whole new way in which truth is stranger than fiction.

MR – Like my other videos, I’m setting up a situation and trusting reality to do the job. People might say that my work is absurd, but reality is even more so.

Wayne Gonzales at Paul Cooper Gallery

Paula Cooper Gallery May-June 2007. Wayne Gonzales' paintings of crowds zero in on the American public, emphasising its divisions. Take Merrily Kerr's video tour of this work