Kate Clark makes stand-alone sculptures that look like they belong in a fairy-tale.

Olaf Breuning, at Metro Pictures

Olaf Breuning turns serious issues into a laughing matter.

Zhang Huan, “Blessings” at PaceWildenstein Gallery

After he moved to Shanghai from New York in 2005, Chinese art star Zhang Huan hired a huge staff to man a factory-like studio; the enormous installations that fill PaceWildenstein’s two downtown galleries give ample evidence of the scale of his industry since. But the new work lacks Zhang’s signature risk-taking, making it feel safe, easy to consume—and fashionably “Chinese.”

The show’s centerpiece, a nearly 60-foot-long “painting,” is as interesting for the technique used to create it (carefully spread ash from burnt temple offerings) as for what it depicts: an ambitious Mao-era canal project with potential correlations to ambitious contemporary undertakings such as China’s massive Three Gorges Dam. Zhang’s recycling is also conceptually engaging—using highly symbolic spent materials to create something new, which, in turn, refers to the past. But in light of the artist’s past performance-art pieces, for which he coated himself in fish, oil and honey in a public latrine, or donned a “muscle” suit made of raw meat, the ash paintings lack any sense of transgression.

Likewise, a series of “Memory Doors”—intricate carvings made over historical photos adhered to ancient wooden doors—are beautifully crafted, but their subject matter (peddlers overloaded with wares, farmers loading a truck) is more illustrative of China’s shifting economy than particularly illuminating in an art sense. Ironically, the show’s most ambiguous piece—a pregnant giant, covered by animal hides and slumped as if heavily burdened—might symbolize China’s imperiled natural world, but it could also stand in for the unfortunate taming of one of China’s most provocative artists.

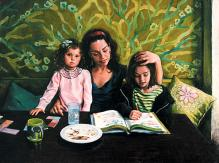

Delia Brown, “Precious” at D’Amelio Terras

Delia Brown paints subjects we love to hate. In the past, she’s depicted herself and her friends in a manner blatantly intended to arouse jealousy—flaunting their youth, sexiness and supposed wealth. Her latest series still unfolds amid the trappings of (borrowed) luxury, but adds cute kids as props in saccharine portraits of the artist and other women (none of whom have children, according to the gallery statement) playing happy mom. As tidy and controlled as her earlier scenes were louche, Brown’s vision of motherhood is as irritatingly unrealistic as it is incisive in exposing unattainable ideals.

Brown has claimed Mary Cassatt as an influence, but even Cassatt occasionally pictured a feeding or diaper change, labors that Brown ignores. Instead, cooperative children are seen lounging with carefully preened moms on cozy beds or couches in immaculate homes; it’s unclear whether the little darlings are “precious” for being themselves or for serving as must-have possessions.

Brown may have intended some sort of meditation on class and parenting, but the absence of affection between mothers and kids, and the sterility of their settings, are more evocative in revealing how hard it is to step into someone else’s reality. What starts out as another provocation turns into a confession of self-doubt, a 180-degree turnaround from the cockiness of her earlier work. Poignant and decidedly less frivolous, these latest panels signal that Brown is perhaps moving in a more personally risky—but meaningful—direction.

Marc Swanson at Bellwether Gallery

For ‘Time Out New York’ Magazine, April 2008

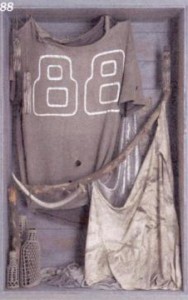

Previously known for sculptures of sequined deer and other strange fauna, Marc Swanson seems to be hunting different trophies in his current show. Although a pile of sparkly black antlers greets visitors, a nearby wall-mounted case – a sort of reliquary containing a grungy football jersey and a swath of glam fabric – indicates that the artist is shifting his aim from animals to humans.

Also new is the incorporation of geometric patterns or diagrams – related, apparently, to personality testing and psychiatric evaluation – into several of the pieces, most chillingly Love is All Around (2007), a video created with Neil Gust. In it, we see a shirtless young man with DEVOTION tattooed across his chest posing against a tinseled backdrop in a red-lit room. A network of lines running over and behind him suggests that not only is his body being subjected to some creepy kind of analysis, but his mind is too. In the back gallery, viewers find themselves similarly dissected, thanks to two sculptural installations incorporating mirrors behind radiating webs of string and wood.

Even more disconcerting is another vitrine in which grimy t-shirts are covered in latex to form a giant hide pierced with thin gold chains. The piece recalls an earlier Swanson effort created out of T-shirts, a sort of boat sail evoking sweaty erotic camaraderie. But here, the resemblance to flayed skin, and the dark undercurrent of the other works in the dimly lit gallery sends a far more sinister message.