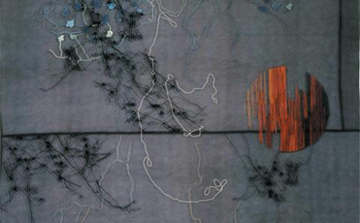

Walead Beshty’s gorgeous new color photograms are the star attraction of his third New York solo show . Yet the artist deliberately endangers their appeal by also exhibiting smaller, drabber, black-and-white depicting the machines that produced them, along with the curators, gallerists and other intermediaries who helped in their realization. In spite of Beshty’s best efforts to expose these energetic abstractions as mere commodities in a decidedly unglamorous chain of distribution, their aura remains undiminished.

As in previous photogram series, in which, for example, Beshty folded sheets of photo paper into freestanding sculptures before exposing them to light, these new images are made within certain parameters, this time involving the use of magnets and rolling techniques. It’s still unclear why Beshty has juxtaposed them with other images that are so different is size, color and mood. To do penance for dallying with pretty pictures? To draw some sort of parallel between the mechanics of the darkroom and art market?

The anthropological quality of the black-and-white portraits, which are titled not by a subject’s name but by his or her job description and nationality, along with the place and date of the photo, stands in cold contrast to the warmth of the almost glowing photograms. Maybe next time Beshty could relegate process to the background, and allow the artwork to take center stage.