If you enjoyed my recent post featuring Brazilian artist Maria Nepomuceno’s vibrant abstract sculpture, see more of this gorgeous exhibition in the video below. With her repeated curving, organic forms, Nepomuceno aims to represent movement into our own inner depths as well as an expansion into the infinite.

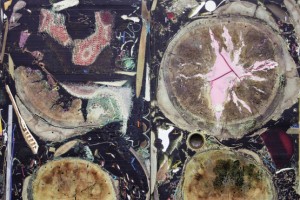

Jedediah Caesar at D’Amelio Gallery

As he did for his 2010 show, Jedediah Caesar pairs gorgeously hued cast-resin sculptures with drabber offerings in his latest outing, necessitating an unfortunate choice for viewers: Fall back on enjoying the now-familiar resin pieces, or try to engage the work that’s not as compelling.

Caesar creates the former by embedding found objects (in this case, rocks collected in the Mojave Desert) into blocks of variously colored resins, before slicing the forms like a loaf of bread to reveal whatever formal arrangements chance created. The latter are represented here by three bulky, sand-castle-like sculptures made of clay, stamped with the imprint of various hard-to-identify items sourced in New York. The impressions left behind include wedge shapes, dots and dents suggesting a little pig sticking its nose where it didn’t belong. Unlike the resin pieces, which have an insect-trapped-in-amber allure, the clay works seem inert, presenting a sense of disconnection in lieu of a poetic evocation of absence.

For some of his previous resin pieces, Caesar sawed off thin tiles to form stacks, or grids on the walls. Here the highlight consists of similar rectangles assembling into a baseboard around the gallery, proceeding in the order in which they were originally cut. This affords an opportunity to see how various patterns unfold and surprising associations arise. Klimt’s jewellike decorations come to mind, but at heart, Caesar’s process is about making the mundane seem extraordinary—or at least aesthetically pleasing.

Aaron Curry, ‘Buzz Kill’ at Michael Werner

When asked how he felt about his imitators in a 1962 interview, Alexander Calder replied, “They nauseate me.” Aaron Curry’s recent sculptures—which continue to blatantly quote the biomorphic forms pioneered by Calder, Frederick Kiesler and other High Modernists—suggest he wouldn’t mind irking his art-historical predecessors. The show’s tongue-in-cheek centerpiece, Buzz Kill (a hot-red rendition of a Calder-like stabile in aluminum), as well as other sculptures featuring curvy interlocking shapes à la Kiesler and Noguchi, seems eager to take down modernism’s utopian ideals without offering much in their place.

The space-hogging Buzz Kill—along with a grainy black-and-white wallpaper of Minimalist collage patterns that plasters the space, floor and ceiling included—hints at a major statement by aggressively altering the gallery’s townhouse setting. But the work fails to go beyond a kill-the-father treatment of modern art. A recurring image within the wallpaper resembles a straight razor at first glance, and a disembodied cardboard “head” briefly conjures dread, before the limp phallic protrusion it dangles from disperses any serious reaction.

The pieces in the foyer (small paper collages featuring a sci-fi sex-goddess type atop a primitive sculpture, and an alien head affixed to a nude female totem) prime viewers for a transgressive punch that the exhibition fails to deliver. Instead, we get more of the artist’s now-signature wooden sculptures composed of organic, interlocking shapes, including Dezvil, which doesn’t resemble an evil presence so much as a goofy moose with someone clinging to its back. The modernist hope of creating a harmonious society through art may be dead, but stasis and pastiche aren’t suitable replacements.

Virginia Overton at The Kitchen

Virginia Overton’s habit of using unexpected objects to challenge our experiences of a particular space would seem well suited to the Kitchen. Yet the five sculptures she presents in this exhibit—made from steel pipes, two-by-fours, pedestals and other items collected behind the scenes at this venerable nonprofit—don’t greatly alter our sense of the institution, though they do reflect on the relevance of Minimalism today.

In the past, Overton’s sculptures have sometimes involved startling incongruences, but the pieces here—like a collection of well-used rigging poles propped against the wall and lit to create an elegant installation—look more attractive than out of place. Others carry on a more overt conversation with 1960s Minimalist art, such as the strongly spotlit, diagonally wall-mounted steel bar that recalls a Flavin fluorescent tube, or the floor-bound array of creaky two-by-fours that noisily raise one’s awareness of his or her footsteps, à la Carl Andre.

These two pieces and others touch on Minimalism’s penchant for interacting with or altering the exhibition space, but Overton ostensibly wants to elicit a deeper understanding of the venue’s identity (in this case, as a gallery and a theater). By quoting Minimalist aesthetics, she brings to mind concerns with light, space and viewer participation, all topics clearly relevant to the Kitchen’s history as a performance center. Considering the highly experimental nature of that history, however, Overton could have taken more risks, instead of just settling for tasteful arrangements.

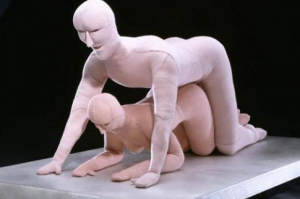

Monica Cook, ‘Volley’ at Postmasters

Figurative sculpture of fantastical creatures being rare in Chelsea, Monica Cook’s first New York solo show starts out as strange, but gets more eccentrically alluring. A monkey-like character by the door sets the tone with a dignified look in his eye but a half-finished, diseased-looking body. His simian brethren, in sculptures, photos and a stop-animation video, are equally grotesque, cobbled together assortments of fur and plastic. They recall David Altmejd’s gaudy giants, but elicit more sympathy.

A parent-and-child grouping and a female with her dog hint at the possibility that the beasts are stand-ins for us humans. This suggestion is confirmed by the video, in which the critters court and mate in a manner recalling Cook’s excellent 2010 YouTube Play contribution (not in the show), featuring romantic encounters driven by bestial desires. Things work out better in Cook’s animal kingdom, however, as ulterior motives fall by the wayside and, after a series of shy glances, a male magically impregnates a female by merely proffering her a bauble.

The fact that this pretty seed was torn from a fetus-like pod, or that the female attracts the male by munching on an olive-like oval pulled from the skin of her leg, is the repulsive flip side to these creatures’ damaged beauty. Missing flesh reveals skeletons cleverly constructed from coiled phone cords, internal organs made of glass balls and baboon bottoms filigreed with lingerie-like ornamentation. Despite their disconcerting appearance, their rituals of attraction and reproduction are sincere and absurdly simple, offering a kind of prelapsarian seduction of their own.

Uta Barth Solo Show at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

The centerpiece of Uta Barth’s latest solo show is a photo series depicting a continually morphing strip of light beneath her living-room curtains, a preposterously simple conceit which nevertheless yields complex optical illusions. As this diaphanous sliver shifts course over an afternoon, it variously resembles a snake, a line on an EKG or a trail of cigarette smoke, all the while transforming the space between the camera, the curtain and the window into an ambiguous territory where volumes flatten or swell, and light can pass for white paint.

Two glimpses of Barth’s hand arranging the curtain folds remind us of her agency, but it’s nature’s hand that propels the work’s attractively simple narrative as the sun’s changing position gradually increases the width of the band. At this time of year, as the onset of winter makes Barth’s invitation to contemplate sunlight especially attractive, the work entices us into the pleasures of solitary idleness that are at odds with the pace of everyday urban life.

In the back room, by comparison, a second group of photographs depicting built-in closets and drawers in the artist’s bedroom seems coldly architectural. Each image is emblazoned by squares or rectangles of light cast from an opposite window: One features a particularly bright patch that suggests celestial or alien visitation; another, a band of shadow over a door latch, creates the illusion that the surface of the print is scratched. But otherwise, the real drama of transformation takes place in the front gallery.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 839, Dec 1-7, 2001.

Sarah Braman, “Yours” at Mitchell-Innes and Nash

Sarah Braman’s trademark combinations of disparate materials in precarious arrangements achieve a new level of gravity with the incorporation of components from a cut-up camper. In her debut at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, hefty chunks of the vehicle act as both painting surface and gritty foil to the clean-cut cubes of gorgeous blue and purple Plexiglas to which they are sometimes conjoined. The resulting juxtapositions defy expectations as the funky, roughed-up trailer becomes impersonal, and the slick geometric elements charm with their transparent beauty.

In a sculpture near the gallery entrance, the back of the RV creates an archway with two Plexi boxes forming an L. Tinted the color of limousine windows, the latter are doodled with spray paint, recalling Sterling Ruby’s defaced pedestal pieces, but without the air of menace. If this treatment somewhat softens these cold, corporate forms, a lack of any trace of habitation within the camper does the opposite, making it makes seem less like a repository of past adventures, à la Mike Nelson’s airstream installation at 303 Gallery last spring, and more like one of Gordon Matta-Clark’s deconstructions of an abandoned place.

In a piece titled 8pm, a smaller fragment of the camper is sandwiched between two aquarium-like shapes, while a larger nearby structure in blue, pink and purple Plexi recalls an empty Damien Hirst shark tank crossed with an Anne Truitt. But it is in Braman’s misleadingly titled and exceedingly lively Coffin that viewers are finally offered the delayed gratification of imagining past lives. Here the Plexiglas takes something of a backseat to a segment of camper laid with a mirrored floor, creating a boudoir-like stage for memories.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 837, November 17-23, 2011.

Tris Vonna-Michell at Metro Pictures Gallery

In his New York gallery debut, British artist Tris Vonna-Michell explores the stories of little-known historical figures (an East German border guard, a forgotten concrete poet) in a group of distinct but linked installations that collect, sift and reconfigure information to create intriguing, and charmingly quixotic, alternative histories. Despite deliberately low-tech, low-key visuals—slide shows of bleak urban scenes, displays of texts on tables and shelves—the artist’s soundtrack of urgently delivered word streams provides an irresistible hook.

In the darkened front gallery, a voice speaks pressingly about magnetic tapes, tanks and Russians, while a projector slowly flashes images of the former no-man’s-land near the Berlin Wall. Texts spell out the story of a young soldier canonized by the East German state for being shot by defectors escaping west in 1962, but the actual details are left untold because, as the piece suggests, truth was subsumed by official legend long ago.

Elsewhere, Vonna-Michell tells of his not entirely successful attempt to track down an obscure French avant-garde poet, Henri Chopin (a former neighbor), and also recalls the 1989 mass demonstrations around Stasi headquarters in Leipzig, as nervous authorities shredded incriminating files inside. Seamlessly segueing from their frantic efforts to destroy records to Kurt Schwitters’s collage technique, Vonna-Michell demonstrates that while none of us may ever completely know the past, it can be engaged, at least, on one’s own terms.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 832, October 13-19, 2011.

Matthew Ronay, “Between the Worlds” at Andrea Rosen Gallery

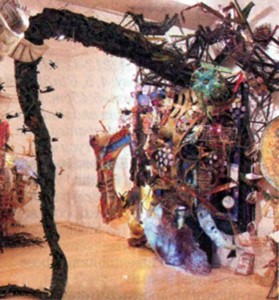

Four years after Matthew Ronay overhauled his style from comic grotesque to soberly spiritual, his ambitious new installation feels like an apotheosis. Dramatically veiled behind a huge black curtain, an enchanted forest populated by birds of prey, totemic figures and fertility symbols invites pleasurable discovery and even a sense of wonder at the level of detail, imagination and effort involved. A lingering question remains, however, as to what you’re supposed to do with this otherworldly space.

Considering that Ronay’s previous pieces have included sculptures of hamburgers alongside delicately arching penises with bites taken out of them, it’s hard to believe that the artist is being entirely straight-faced here. In the gallery handout, he suggests that he wants to give gallerygoers an opportunity to transcend the quotidian by offering them a genuine spiritual experience. Yet with all the papier-mâché volcanoes, trees made of Ikea-like prints, diminutive beings and the cutest owls this side of Disney lying about, they’ll have to stop chuckling first.

Abundant mushroom imagery (growing on felled trees, hanging in chains) suggests some sort of transport of the mind. But it’s the commanding Masculine Pillar—a robed column with a giant eyelike symbol—that grabs attention by virtue of appearing to conceal someone inside, as it did on the show’s opening night, when Ronay occupied it. Which is a reminder that while forests are classic settings for fantastical tales, characters are what make a story, so Ronay’s installation feels a little hollow when it’s empty. Without the presence of a person, the installation is like a stage set, and all the totems simply props with no ritual significance to add to their relevance. Thus, the piece’s potential to achieve the artist’s hoped-for transcendence is diminished.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 823, August 4-10, 2011.

“The House Without the Door” at David Zwirner Gallery

Mona Hatoum’s 1999 sculpture Home (featuring kitchen implements with wires running out of them, accompanied by the sound of pulsating current) inspired this unsettling exhibition plumbing the darker side of the places in which we live. High on anxiety but regrettably low on risk factor, this hit parade of big-name artists still affords the pleasure of reconnecting with iconic artworks about painful circumstances.

Family relations simmer in the show’s best pieces. Louise Bourgeois’s claustrophobic house teeming with phallic/breast/fungal forms and Rachel Whiteread’s black urethane mattress creased by a labial fold conjure a dread matched by a Luc Tuymans painting of place settings that foretells the drama of a family gathering.

Violence spills over in Gregor Schneider’s photos of a strung-up sex doll and in Mamma Andersson’s painting of a disordered bedroom with ominously bloodred furniture. But the most disturbing pieces hint at souls lost to the chaos (Jeff Wall’s photo of a disheveled character standing by the door of his decrepit domicile) or obsessive order (a Thomas Ruff living-room scene) of their lives.

Even a cheery painting of a beach house by Maureen Gallace turns suspiciously, unbelievably idealized in this context, while a whimsical paintbrush by Michael Brown, its handle crafted from melted Neil Young records, seems primed for a cover-up. Viewed from the right angle, David Altmejd’s plaster sculpture of a fantastical lair with dangling staircases turns out to be the head of some deranged giant. Such twists add intrigue to this domestic thriller of a group show.

Paul Sietsema at Matthew Marks Gallery

If it weren’t for the schooner by the doorway at Paul Sietsema’s first New York gallery solo, I’d have missed the boat. Not-quite-right details reveal that what looks like an aged old photograph of a sailboat is in fact a meticulous drawing that demonstrates in a flash how painterly skill adds value and interest to an artwork. In this otherwise aesthetically restrained but intellectually stimulating show, Sietsema allows trace evidence of his hand in pieces that look digitally produced or printed, questioning his own role as a craftsman in the digital age and floating an inconclusive but engaging argument that artistic survival means cleverly thwarting expectations.

In the past, Sietsema has exhibited films of sculptural objects; the drawings here allow us the intimacy to appreciate his handiwork. Two untitled pieces resembling expressive abstractions in black ink also include depictions of bottles of Krylon ‘Short Cuts’ paint, humorously highlighting how Sietsema doesn’t take shortcuts in his labor intensive, cerebral, and non-emotive project. At the bottom of one, the phrase “broken down and experimental…broken down beauty,” bespeaks the pleasure of piecing together Sietsema’s deconstructions.

Two pieces titled, ‘Painter’s Mussel’ refer to shells used to hold paint but show Sietsema flexing his intellectual muscle in complicated pictures of disassembled framed photographs drawn to resemble photographic negatives which appear to have been printed. From the aged photograph of the boat and images that pit old technology (the brush) with new, to two pieces replicating the dated medium of newspaper pages (including an article on Obama reversing a Bush policy) Sietsema suggests that with passage of time ascendency fades – the smart artist adapts by working outside of traditional expectations.

Condensed version of this review published in Time Out New York, issue 815, June 2-8, 2011.

Laurel Nakadate at Leslie Tonkonow Artworks and Projects

Laurel Nakadate cried every day of 2010. And whether she was in her apartment, in an airplane lavatory or on a beach, she captured the result in 365 photographs, meant to document her effort, as she put it, to “deliberately take part in sadness.” Contrary to this suggestion of shared unhappiness, however, the images portray her in isolation. Often nude or semiclothed, she plays the role of a vulnerable woman needing rescue, appearing to offer her body in a compromised sexual exchange for attention. Sensational, narcissistic, yet incisively illuminating in some respects, Nakadate’s project is an uncomfortable portrait of alienation.

It also tests our willingness to indulge in so much self-inflicted pain. The seasons and the artist’s travels introduce a minor narrative arc, but there’s no resolution to her misery. Unlike Tehching Hsieh’s yearlong performances tracking the effects of self-imprisonment, or Eleanor Antin’s photo diary of being on a diet, Nakadate undergoes no transformation and promotes no politics, personal or otherwise. And unlike the lovelorn Sophie Calle’s exhaustive investigation of a Dear John letter, there is no catharsis.

Instead, the act of repetition dominates, and the mind wanders to questions about Nakadate and her motives: How does she make herself cry? Is she merely acting? What goes on off-camera: Does she happily go about her day until the requisite moment to shed tears? Part of “365 Days” is on view at MoMA PS1, where the photographs are huge, implying an unwarranted monumentality to the artist’s questionably authentic emotion. Even in this more modest installation of smaller-size prints in a tight grid arrangement, Nakadate is still center stage, limiting any possible commentary on collective grief or widespread disaffection.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 815, June 2-8, 2011.

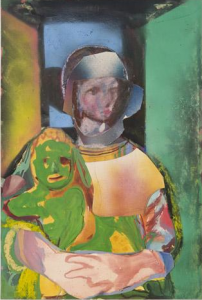

Angel Otero, “Memento” at Lehmann Maupin

Angel Otero’s unconventional process—fashioning assemblages or lively paintings using “skins” of oil paint applied to glass before being peeled off—is the draw in his New York solo debut. An awkward anthropomorphic object perched on a chintzy armchair, messy Expressionist interiors in garish colors and one uninspired composition with text demonstrate the young artist’s competing sensibilities. Far better are Otero’s large-scale abstractions—action paintings in which paint itself seems to have agency, shooting off the edge of the canvas, bunching dramatically or seductively veiling its support.

The show’s smallest and punchiest piece—a black number whose surface is concertinaed like a crushed soda can—has an affinity with Piero Manzoni’s pleated white canvas, but in place of purity there is an excess of paint, piled up in waves as if to hide some (perhaps failed?) experiment beneath. Likewise, a blocky form wrapped in streaks of yellow and black traffics in concealment, channeling Christo’s early wrapped objects—minus, unfortunately, the mystery.

The play between a vibrantly colored surface and an occasionally glimpsed support that is waxy and dead is more alive than, say, Steven Parrino’s twisted and pulled canvases, and aligns Otero with Fabian Marcaccio’s use of paint as a sculpting material. Recurrent blurring also recalls Gerhard Richter’s scraped abstract canvases, but unlike Richter, Otero’s intent is to build, not cancel out. His undulating skins re-create the drama of a hastily drawn curtain, awaking the senses and offering a celebration of paint’s possibilities.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 807, March 31 – April 6, 2011.

Yoan Capote, “Mental States” at Jack Shainman Gallery

Yoan Capote, a stand-out artist in the Havana scene, explained in a recent interview that he wants his work to remain relevant after the ‘political exoticism’ of Cuban art (fashionable since the mid-90s) dies down. In the meantime, his recent subject matter – the allures and disillusionment of migration – and his tendency towards often blunt, sometimes profound statements are the hallmarks of stereotypical Cuban style. Despite the feeling of déjà vu that this show evokes, Capote makes his mark by implicating everyone – us, himself, and Cubans in general – in the complex pleasures and pains of cross-cultural longing.

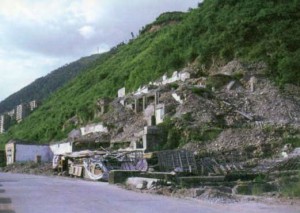

Capote opens the show with a literal bait-and-switch – a majestically vast (over 26 foot long) and gorgeously deserted seascape that turns out on closer inspection to be an intimidating composition made from thousands of fish hooks attached to the picture’s surface. An equally enticing sea view crops up again in a nearby video in which we watch a waterfront window being bricked in with the pattern of a U.S. flag in a claustrophobic ritual that replaces the imagined but unattainable reality of foreign lands beyond the horizon with a barricade both symbolic and literal.

Surprise menace and repressive restriction create an uneasy mood but leave room for personally inflected interpretation. More heavy-handed pieces kill the spirit of enquiry, as with a room-sized bronze set of scales titled ‘Status Quo (Reality and Idealism)’ that leaves no doubt about how privilege tips in favor of the already powerful. In a series titled ‘Coitus’, human silhouettes cut from dollar bills, pesos, rubles and Yuan play the one-dimensional role of symbolic aggressor or victim. But in pieces like ‘Migrant,’ in which two feet join to tree trunk legs that end in a complex network of roots, Capote pointedly testifies to the personal cost of uprootedness. Laid low on the gallery floor, roots echoing brain synapses make the poignant argument that when it comes to the linguistic, social or cultural nourishment of your native culture, you can’t take it with you.

Originally published in Flash Art International, issue 276, January/February, 2011.

Sean Bluechel, “Another with Suspension” at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery

As far as quantity goes, the 36 ceramic sculptures and 25 photos crowding Nicole Klagsbrun’s side gallery suggest that Sean Bluechel is more than ready for his first major Chelsea show. In terms of quality, however, his creative profusion—and a goofy hedonism conveyed by ubiquitous smiley faces, multiple ceramic spliffs and an assortment of phallic objects ranging from digits to a corncob—threaten to distract from the show’s real gems: Remarkable shape-shifting objects conjure fantastical scenarios.

Though the ceramics are the main draw, Bluechel’s photos of totemic assemblages cobbled together from cardboard tubes, Styrofoam, tinsel, balloons and a very accommodating nude woman (who seems to have been shot in a basement) have a furtive quality, as well as a postdebauch air that is in keeping with the sculptures’ juxtaposition of lumpen forms and beautifully colored glazes. Yet they feel more like high jinks than high art.

Bluechel’s apparent references in a few of the sculptures to such artists as Jean Dubuffet and Yves Klein indicate that he’s mindful of the distinction. Yet his efforts work best when you overlook the visual hubbub of his busy installation and focus on select stand-alone pieces: the upside-down mushroom balanced on two blobs, titled Unshaved Wicca Girls; the quasi-camera/gun/musical instrument, rising from a dish amid a flurry of leaves, titledKill Vegans; the Kusama-channeling bouquet of protruding fingers crowned with a laurel. They all deliver their paeans to insouciant perversity with concision and humor.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 799, February 3-9, 2011.

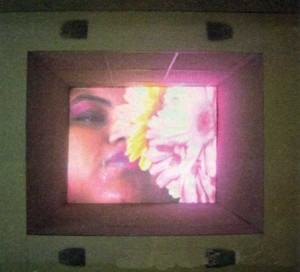

Tiffany Pollack, “Room” at Gasser & Grunert, Inc.

In Tiffany Pollack’s second solo show, baby care and flowers are subjects for dyed silk paintings in glorious washes of beautiful color. The former take shape as quasimodernist grids charting the waking/napping routine of the artist’s infant. Given that mother-child relationships in contemporary art tend more toward the curdled Robert Melee variety, Pollack’s approach is surprisingly anxiety-free.

Though the show includes eight such paintings, Pollack crystallizes the experience of all-encompassing emotional highs and lows in a single piece that registers periods of happiness followed by tears. Like Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s memorable photos of her children’s slow progress in getting dressed to go out during winter, Pollack’s efforts will elicit groans of recognition, their wavy bands of color perfectly conveying the hazy disorientation of sleep deprivation.

Unlike Ukeles, however, or Catherine Opie’s gender-bending self-portrait while nursing, Pollack’s pretty colors and near-total lack of critical remove suggest that she’s enjoying her new role. Coupled with an eye-popping series of flower paintings in which poppies explode against a hot pink ground, bleeding-heart flowers dangle gorgeous buds, and the gathered stems of calla lilies melt together in a downward rush of paint, Pollack revels in the pleasures of fertility. These works recall Charles Ray’s much-lauded room of flowers at the last Whitney Biennial, though they leave hanging the question of whether highly personal exploration, beauty and, in Pollack’s case, pure joy are enough on their own.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 798, January 27 – February 2, 2011.

Matthew Monahan at Anton Kern Gallery

For a card-carrying member of the “Unmonumental” generation of sculptors (he was actually in the New Museum show of that name), Matthew Monahan’s latest freestanding bronze sculptures are both reactionary and a logical next step. His previous work consisted of installational displays crowded with objects and figures, idiosyncratic minimuseums chockablock with visual allusions to art history—a Greco-Indian eye here, a Northern Renaissance visage there. At Anton Kern, Monahan distills archetypal characters from a jumble of references, creating a fascinating group that looks like archaeological finds from an alternative art history.

One slender nude’s wire-bound body recalls photographer Nobuyoshi Araki’s soft-core titillations, but her quizzical expression is more provocative, suggesting spiritual superiority and/or mental disability. Another character’s cruciform pose begs explaining, but his craggy and practically concave face closes in as if guarding secrets. Nearby, a motionless, gold-leafed droid version of Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Spacestands stiffly by.

While Monahan’s sculptures pique our curiosity with their mix of vague familiarity and uncertain identity, a series of oil-on-board images resembling tantric diagrams fairly exudes esoteric mystery. Collectively titled “Body Electric,” they summon Walt Whitman’s passionate appreciation of the human form but feature a fairly unnuanced, everyman element: a simplified kind of line drawing made by scraping black-painted paper to reveal the white below. The sculptures, on the other hand, turn appropriation into creation with their affecting cast and enjoyable synthesis of history, pop culture and sheer invention.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 793, December 9 – 15, 2010.

Kristin Morgin, “New York Be Nice” at Zach Feuer Gallery

The nervous plea in the title of Kristen Morgin’s New York solo debut seems warranted at first glance. This accumulation of meticulously crafted, painted-ceramic replicas of comics, toys, personal mail and more, laid out on rickety tables, looks like the world’s most precious yard sale. But behind a facade of understatement, Morgin cleverly challenges the ways in which we value things, making art that’s real and fake, handcrafted and reproduced, imitative and innovative, vintage and new, high and low, all at the same time.

Category-busting begins at the door with a shelf of roughly fashioned teacups featuring portraits of comics icons, from Wonder Woman to Snoopy, a cheeky mix of useful craft and pop-indebted fine art. Elsewhere, doodles on Post-its lie alongside a ceramic Curious George book, featuring the trouble-prone primate traveling through space. Despite its futuristic theme, the tome’s deliberately cracked and aged condition and added-on sketches—including a version of Picasso’s Guernica—summon a specter of ruin over predigital ephemera. Large drawings of a dodo bird and ticking clocks rendered over other ceramic facsimiles of comic books likewise reinforce the sense of imminent extinction, reminding us that the past is always mediated.

What would ordinarily be the show’s star attraction—a pale and crumpled replica of the Porsche Spyder in which James Dean met his end—is the Bamiyan Buddha of roadsters: a memory so wrecked that it’s barely related to the original. Morgin, however, isn’t after the trompe l’oeil virtuosity of Steve Wolfe or even Allen Ruppersberg’s reshuffled pop references. Instead, she gives us a pointed warning that everything starting out shiny and new inevitably crumbles to dust.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 791, November 25-December 1, 2010.

“Greater New York” at PS1

The third of three blockbuster contemporary art survey shows to hit New York in the past year, Greater New York was worth waiting for. The New Museum’s youthfest, The Generational, showcased an under ripe generation still finding its voice. The Whitney Biennial presented artists self-consciously grappling with new ways to be ‘experimental.’ Despite the fact that these shows shared several artists, Greater New York swapped the previous ‘watch-this-space’ vibe for mature, confident work by 68 artists and collectives, evenly balanced between male and female, whose collective fostering of identity politics – sexual, racial, political and personal – broke with recent art world trends towards hermeticism and reconnected with the larger world.

If identity politics has come to sound retro in ‘post-black’ days, Hank Willis Thomas’ monumental photo series made it joltingly relevant, connecting yesterday to today by tracking the persistence of stereotype and recent fantasies of racial integration through forty years of magazine ads. Rashaad Newsome’s video of over twenty female performers uttering partial phrases like ‘excuuuuuse…’ or ‘giiirl’ is one of the best pieces at PS1 (though technically part of an auxiliary exhibition reviewing the last five years of artmaking), succinctly demonstrating how slang and role play create exclusive group identities.

Alternative sexuality was the norm in the third floor galleries, where Sharon Hayes’ five channel video installation ‘Revolutionary Love’ brilliantly integrated the concerns of participants inside and protesters outside the 2008 Democratic and Republican National Conventions before veering quixotically off topic by demanding love along with legal rights. But her assertion, ‘we’re all queer’ makes perfect sense in light of Leigh Ledare’s creepily incestuous photos of his exhibitionist mom, which prove that anyone, heterosexuals included, can pretty much chart their own course. LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photos of her own mother come to mind (from the New Museum Triennial); in her video contribution here, her tense, naked torso – juxtaposed with clouds of factory steam – pulsated with unspoken feeling.

Proving that identity politics don’t have to be dour, K8 Hardy’s fabulously eclectic self-portraits in outrageous getups place her characters outside recognizable ‘types.’ A similar inventive exuberance carries downstairs to A.L. Steiner’s photocollaged lesbian utopia where one nude joker embraces a reproduction of Courbet’s ‘Origins’ and another dangles her pendulous breasts over two globs of dough. Identity aside, other galleries exploded with color or formal inventiveness, including Kerstin Bratsch’s and Adele Roder’s abstract paintings, which distill distinctly a modernist appeal in terms of color and geometry, and Mariah Robertson’s audacious, show stopping 30” by 100’ photogram wrapped around gallery floor, walls, and ceiling.

Press material posited the ‘process of creation and the generative nature of the artist’s studio’ as the show’s dominant theme, though Robbinschild’s installation conveyed little when the artist’s weren’t present, Ei Arakawa gave out candy to studio visitors one day in apology for lack of a performance, and The Bruce High Quality Foundation’s program to swap new pedestals for used ones from art collages was a space-hogging one-liner. On the other hand, Naama Tsabar’s ‘Speaker Wall,’ two walls of bookshelf speakers rigged with strings into irresistible collaborative instruments, generated the hive of activity that the curators must have hoped for.

Tsabar’s invitation to engage in her work was literal, but for the most part, Greater New York’s best pieces stood out for their complex engagement with issues outside the art world (gay rights, racial, class and gender politics, etc). A couch featuring news clippings of President Obama and photos of a disfigured young Marine were among the most memorable images of the Whitney Biennial; likewise, pieces like David Brook’s living trees encased in concrete – a protest of deforestation in the Amazon, amongst other things – made the connection to an existing conversation amongst a wider audience, making this show the one we’ll likely continue to talk about.

Originally published in Flash Art International, no 274, October 2010.

Polly Apfelbaum, “Off Colour” at D’Amelio Terras

Polly Apfelbaum is in rebellion. Unlike the pleasing forms and intricate color schemes of the floor-based fabric arrangements she’s known for, her latest installation of jagged panels in sequined cloth is attention-grabbing but jarring. Off Colour derives its title and loud appearance from amateur nude photos that Apfelbaum found at a London flea market, suggesting a futile attempt at titillation.

At previous shows Apfelbaum had brought in work crafted in her workshop, but this installation was made directly in the gallery. The result—slender fabric strips extending into the corners or hugging columns—could barely be termed a response to this unremarkable space, though the artist has upended expectations by diverting our attention from the walls to the floor. Still, tiptoeing between the zones of crimson, pink, yellow, green and orange (that a sign warns us not to touch) is more awkward than absorbing; the scheme is so calculated that it discourages any desire for interaction.

On the plus side, the panels’ rough edges, geometry and scattered appearance recall Jean Arp’s torn-paper collages, and look like they might harbor some sort of meaningful relationship between the shapes and the negative spaces they create. Unfortunately, a more concrete reading is elusive, as if Apfelbaum had deliberately left behind a self-conscious collection of isolated parts that, like her source photos, lead us on but give us no satisfaction.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 785, October 14-20, 2010.

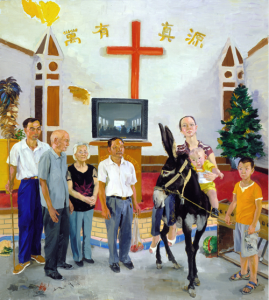

Liu Xiaodong, “Yan’ Guan Town” at Mary Boone Gallery

Coincidently, while Liu Xiaodong painted this show’s realist portraits of a Muslim and a Christian family in China’s northwestern Gansu province, ethnic violence broke out between Muslim and Han Chinese in the region. Rather than an argument for peaceful coexistence, however, this body of work seems more motivated by the artist’s curiosity about the unique cultural adaptations of China’s religious minorities.

Coincidently, while Liu Xiaodong painted this show’s realist portraits of a Muslim and a Christian family in China’s northwestern Gansu province, ethnic violence broke out between Muslim and Han Chinese in the region. Rather than an argument for peaceful coexistence, however, this body of work seems more motivated by the artist’s curiosity about the unique cultural adaptations of China’s religious minorities. Complicated family dynamics and Liu’s own idiosyncratic symbolism add animation to already fascinating portraits.

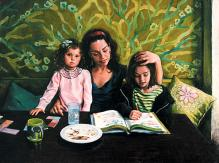

For example, Liu places the Christian brood of Z’s Family inside a chapel, with the young mother astride a donkey while holding her antsy toddler in her lap: an image inspired (according to an entry from the artist’s diary, included in the show’s catalog) by Jesus’ flight into Egypt as an infant. Just as compelling, though, is the painting’s psychological undercurrents, particularly in a woman’s beatific expression, which barely conceals her apparent discomfort. More cryptically, a male relative on the left stands with a giant feather duster in his hand, suggesting some sort of emasculated posture, while the 80-year-old patriarch’s downcast glance conveys weakness as much as presumed humility.

The Muslim H’s Family is seen gathered together in the cramped restaurant that doubles as their home. Four adolescent daughters and a son strike awkward poses but telegraph their individuality by boldly meeting Liu’s gaze. So it seems odd that Liu asked the lively, eldest daughter to wear a head scarf (not owning one, she had to borrow one), then painted her odalisque-style in a cabinet-like enclosure in the background, which serves as a bed for the girls.

Both canvases recall the anthropological air of Thomas Struth’s family portraits, but Liu adds layers of interpretation that symbolize the challenges of understanding others.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 784, October 7-13, 2010.

Judith Eisler, Bryn McConnell, Mariah Roberson at Greenberg

Painting and photography intertwine in this handsome if disparate show in which success hinges on how provocatively each artist elaborates upon her source material. Judith Eisler’s canvases of music or film stars seesaw between the bland and glorious, Mariah Robertson’s unique prints picture ambiguous spaces in eerily alluring color, while recent SVA grad Bryn McConnell limns vibrantly toned, if shallow, renditions of fashion spreads.

McConnell’s composition of a model draped over the edge of a bed is the show’s most attention-grabbing piece; its glowing orange and yellow highlights make Eisler’s two adjacent monochromatic paintings of Romy Schneider appear lackluster by comparison. Yet McConnell’s effort feels vacant, as she strips the identity of her subject—a model from a Miu Miu advertisement—reducing her to little more than a series of painterly strokes. Eisler, on the other hand, uses appropriated film stills to play up Schneider’s momentarily masculine look, nearly crushing her starlet charm. Similarly, in another nearby piece, Eisler seemingly morphs Deborah Harry into an astronaut by showing the singer as she retreats into a gorgeous blue shaft of light on a dark, smoky stage.

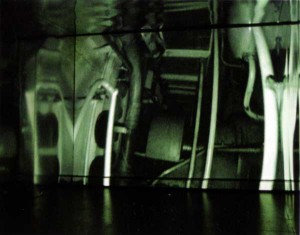

The artsy nudes and repeated palm motifs Robertson incorporates into her collagelike compositions look like borrowed stock photography, but they were actually created by the artist, who plays with photographic conventions. More pleasurable, though, are her purely aesthetic touches: horizontal bands of sunset colors, multiple images of an anonymous figure on a rooftop, and drip patterns, all creating an abstract scenario in which the imagination is set racing.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 777, August 19-25, 2010.

Martin Schoeller, “Female Bodybuilders” at Hasted Hunt Kraeutler

Can photos of babes in bikinis with big biceps be more than gratuitous? Martin Schoeller’s portraits of women bodybuilders pander to the inherent sensationalism of their topic, but also manage to transcend it, playing up deeply disconcerting contrasts between traits typically considered female (makeup, hair) and male (bulging muscles). He puts his subjects on pedestals as goddesses of discipline and self-control. By contrast, a second body of work largely deglamorizes the faces of celebrities who’ve agreed to pose for his flaw-baring lens.

In the former series, Schoeller magnifies his sitters’ bulk, framing them from the waist up in enormous 61.5″ x 50″ photos. The same women (e.g., Christine Roth, Carmella Cureton) appear on bodybuilding blogs and websites in more feminine—and, perhaps, objectifying—poses, but Schoeller’s gender-bending emphasis on pumped-up arms and abs showcases hard-won physiques that rebuff mainstream ideals of the female physique. Valerie Belin’s images of bodybuilders (who look so shiny as to seem practically chromed) come to mind, but Schoeller’s subjects are proud and unique.

In an ironic reversal, the best photos in the second series are of women with normal features and inflated personalities: an ethereal and unrecognizably dignified Paris Hilton; Sarah Palin, captured as a cipher constructed out of makeup. Most of these other portraits, however, are about as compelling as a driver’s-license picture. Marina Abramovic shows no trace of the pain and drive she’s poured into her career, while deadpan studies of Chris Rock and Jerry Seinfeld, clinical takes on Bill Murray and a dozy Kobe Bryant beg for something to make us take notice—be it brawn, beauty or brains.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 776, August 12-18, 2010.

Carol Bove, Sterling Ruby, Dana Schutz at Andrea Rosen Gallery

At first glance, the works of Carol Bove, Sterling Ruby and Dana Schutz wouldn’t seem to have much in common besides their creators’ hot-artist status. Yet an undercurrent of aggression unites their otherwise disparate efforts. Bove’s unusually severe sculptures, Ruby’s antiauthoritarian sculpture and painting, and Schutz’s gruesome canvases (including one showing a finger sliced in a fan) range from bold elegance to cheeky flipness in their flirtation with darkness.

Bove’s huge Plexiglas-and-expanded-sheet-metal boxes are the surprise of the show: a cold departure from her intimate assemblages of books and ephemera nostalgically evoking the ’60s and ’70s. The diamond-patterned mesh covering the top, bottom and sides of these rectangular objects explains the title, Harlequin, perhaps after Picasso’s predilection for that subject; here, they become obstreperous gatekeepers, obstructing access to the back galleries.

Bove’s works would have made an interesting match with Ruby’s creepy cage sculpture from his last solo show at Pace Gallery; instead, the latter is represented by the comparatively refined Consolidator, a dark-brown sculpture resembling a cross between a cannon and a coffin, whose title, scrawled across its face, exudes a vague corporate threat. A nearby painting references both a notorious nightclub and a supermax prison, starkly contrasting freedom with lockdown.

Lack of self-control afflicts Schutz’s hapless characters, which include an escape artist who’s pinned himself to a target with knives, and the numskull whose appliance-sliced finger has just generated a tasteful if gory modernist abstraction. After Bove’s monuments to the beauty of power and Ruby’s ominous embodiment of fear, Schutz’s tongue-in-cheek portrayals are laugh-out-loud funny, and the highlight of this show.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 775, August 5-11, 2010.

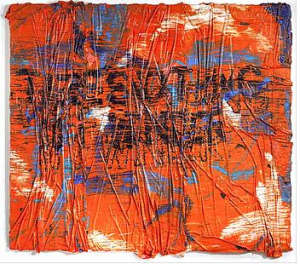

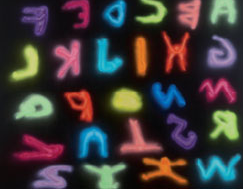

Tala Madani at Lombard-Freid Projects

Tala Madani’s solo show offers relief from the aggressive nastiness of her sadistic characters and their hellish world but, while the mood shift is palpable, it’s still far from redemptive. Legions of tiny male nudes in neon colors on black canvas spelling out the letters of the alphabet are an irresistible lure. But when the letters form words and phrases like in Men R Hot with Fire (2010) (where the ‘t’ is depicted on fire) or in XO with Stripes (2010), they don’t communicate brotherly love. Dehumanized by lack of distinguishing characteristics and gruesome contortions, the characters are no longer perpetrators of abuse; instead, responsibility for their treatment lies with the artist.

Yet a stop-motion animation of a dancer — a standout from the show’s other violent videos — suggests that Madani’s inspiration comes in part from the human body’s astonishing range of movement. This injection of sincerity into Madani’s sinister world is counteracted by cautionary pieces like a giant composed of letters, Leviathan (2010), who hints at the abusive power of language; and an eye exam chart populated by human letters, Eye Exam (2009), which begs the question of what we really see in the world around us. Taking on communication itself as a subject matter, Madani keeps a critical eye while making a welcome break from the claustrophobic world of her past work, opening up promising new directions.

Originally published in Flash Art International, no 272, May/June 2010.

Trisha Donnelly at Casey Kaplan Gallery

It says something when an artist can produce an exhibition of totally abstract artwork that runs the risk of being too obvious, but Trisha Donnelly’s latest solo show is almost unsettlingly easy to read. With no gallery statement and only one titled work, a few things are still left up in the air, but this show’s layout and content make for a pleasant, if straightforward, journey through the artist’s thought process.

A kidney-shaped desk (a found object) titled The Secretary, which greets visitors in front, seems at first uncomfortably obtuse, blocking access while posing the question of what we’re meant to glean from it. Only in the next room do its feminine curves make sense in comparison with a pretty pink marble sculpture, adorned with concave impressions that evoke breasts or eyes and appear to channel Brancusi. It seems we’ve stumbled on the secretary herself, a surprisingly primal creature, minimally altered from her natural state but with striking features nonetheless.

Such amusing opportunities for personification eventually peter out as Donnelly, who used a rotary saw to incise columnar and grille-like shapes into two sculptures, settles for the traditional role of mason. This suggests that while her contemporaries are content to dig into modernist history, Donnelly goes further back in time, mining raw material from the same earth as the ancients (the pieces are made out of limestone quarried in Bolzano, Italy). She calls to mind their labors while producing forms that resonate with contemporary life.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 769, June 24 – 30, 2010.

Patricia Esquivias at Murray Guy

Patricia Esquivias’s immediately likable narrator voice is the hook in her major new video,Folklore III, keeping us engaged through dull, repetitive images and the creeping suspicion that there is less to the historical connections she weaves between two lands—Galicia, Spain; and Nueva Galicia, Mexico—than her deadpan delivery suggests. Unsupported by video evidence, the details Esquivias describes—childlike decorations on the houses, a vast unfinished monument—gradually come to seem more fanciful than believable, and thus, wonderfully entertaining.

Old Galicia represents endings—we see scenes of the coastline and hear about the rituals enacted there—while new Galicia presumably offers a fresh start to immigrants. Yet it’s the Old World that hosts a peculiar and inherently hopeful architectural custom, whereby homeowners build successively larger floors onto their buildings, creating edifices shaped like inverted Aztec pyramids. Such optimism in the future contrasts with the stasis of Nueva Galicia, where newcomers never really find their feet, subtly upending the assumption that newer is always better.

The show’s second major piece, Natures at the Hand, (from 2006) reverses tactics by favoring visuals over story, though it continues to forge similarly tenuous historical or thematic connections—comparing topiary in European castles with that in Guadalajara’s front yards, for example. Collaging disparate images together to create new narratives is a common strategy these days (Fischli and Weiss and Fia Backström come to mind), but Esquivias makes the approach her own by delighting in the simple absurdities of life, and evoking a cross-border culture in which the fluidity of facts meets the charms of quirkiness.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 768, June 17-23, 2010.

Thomas Houseago at Michael Werner Gallery

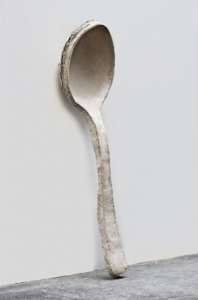

The sculptures in Thomas Houseago’s first New York solo show defy reigning art trends by embracing monumentality, mining art history for subject matter without being overacademic or self-conscious, and conveying meaning without detailed background info. None have the commanding presence or shape-shifting potential of the artist’s towering Baby, a standout in the current Whitney Biennial. But his totemic and iconic pieces, made with labored simplicity, plumb life’s mysteries with hopeful optimism.

A line of skulls just inside the gallery would be grim if not for their wealth of associations, from Darth Vader’s mask to Picasso’s haunting late self-portraits. Jonathan Meese’s Cubist-indebted faces come to mind, but Houseago’s heads are more in keeping with the simple, alien grotesquery of Ugo Rondinone’s all-black visages. With their hollow, zombie eyes, quizzical semi-squints and fingerlike ropes of flesh on their faces, the figures float between life and death, pop culture and high art.

The show itself ambitiously aims to be many things at once—figurative and abstract, humorous and serious, historical and contemporary—but it feels crowded and thematically discordant at times. It’s tempting to hunt for humanist metaphors to tie together pieces like the two giant spoons à la Claes Oldenburg (nourishment?) and the Brancusi-like totem with bird’s head/bike helmet on top (spirituality?). Other objects make more fruitful associations: A repeated circle pattern appearing in a ghoulish face, a geometric frieze, and a sculpture representing sunrise and sunset merges personal and cosmic concerns, connecting dark souls to shining celestial bodies—and speaking for art’s ability to enlighten.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 764, May 20 – 26, 2010.

The Bruce High Quality Foundation University at Susan Inglett Gallery

The concept behind the Bruce High Quality Foundation’s third New York solo show is more engaging than the artwork, which comes as no surprise. The anonymous artist collective’s move to start its own free, unaccredited school is a gutsy and overdue reaction against the pressure on artists to complete costly MFA programs. But just as student work generally hasn’t had time to mature, the sculpture created by the artists known as ‘the Bruces’ in response to the past semester’s discussions and plans for the future is more a collection of ideas than a profound statement.

Sculpture in the form of chalkboards summon the spirit of Beuys, while unusable desks fashioned from broken drywall resemble post-apocalypse Bauhaus furniture; neither looks meant to last. Literally erasable, the chalkboards epitomize the experimental, non-product-driven nature of the Bruces’ approach. Humor is rampant, from a blackboard reading ‘in the future everyone will be a foundation,’ a twist on Warhol’s famous 15-minute bon mot, to a study of art world gender disparity with a female superhero mask and hairdryer balancing a beer stein with a fake breast. Obviously, these artists are having a good time inspiring each other and now a larger audience of ‘university’ attendees. The resulting artwork may not stand the test of time, but it’s an enticing invitation to join the fun.

Originally published in Flash Art International, March – April, 2010.

John Bock at Anton Kern Gallery

The remnants of John Bock’s current performance at Anton Kern Gallery—a floor littered with Plexiglas sheets covered in marker drawings, smiley-face stickers and sausage slices; a suitcase full of handmade, low-tech mechanisms—speak to the artist’s willingness to mine the ridiculous, grotesque and nonsensical in order to build fantastical, alternative realities. The new work, including two videos shot in Korea and a series of wall sculptures, offsets confusion with absurdity, striking an appealing balance between eccentricity and humor.

Bock’s videos feature an assortment of antiheroes who use a revolving lineup of devices to navigate unfamiliar terrain. The live performance distills this same sort of activity, via a hired dancer who tests a series of contraptions cobbled together from wood, stuffing and masking tape, as Bock diagrams his actions in rapid-fire sketches on Plexi. Like an artistic MacGyver, Bock’s resourcefulness in crafting, say, a sandbag-like weapon out of a pair of tights enables his characters to meet the challenges of an illogical world.

Just as performance partially decodes Bock’s frenetic, abstract diagrams, a mini horror movie, Büsche (Box), pokes fun at the psychological drama of a longer video titled Para-Schizo, ensnarled, in which two muttering loners employ totems and devices to walk, eat and engage in a destructive love affair. Their tools don’t fix anything: One character meets an abject death, the other finds a secluded peace, suggesting that while life may present us with obstacles, our efforts to overcome them—reasonably or not—are still valiant.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 756, March 25 – 31, 2010.

Steve Mumford at Postmasters

Steve Mumford may have taken six trips to Iraq in the past seven years, allowing his art practice to be absorbed by picturing the war there, but while his agenda remains curiously ambiguous, he clearly avoids propaganda. In a style inspired by the 19th century American Realist painters, he treats his subjects, from Iraqi prostitutes to Islamic leaders, U.S. soldiers to jihadist fighters with dignity regardless of their beliefs and dealings, a tactic bound to rile his various subjects, never mind his audience.

War is Mumford’s ostensible subject, but the people he depicts are in limbo, not action, putting the emphasis on their individual characters rather than symbolic identity. The prostitutes are modest and brave, huddling together in their black, one-piece swimsuits isolated at the center of an empty swimming pool; a jihadist pausing to write in a notebook on a rocky hillside commands respect as a thoughtful intellectual. Mumford’s paintings work both sides of the fence, eliciting sympathy for a beautiful U.S. soldier who lost her arm one minute, a male suicide bomber who bids a tearful goodbye the next.

Are terrorists worthy of compassion? Sympathy? Mumford shifts the decision to us, obscuring his point of view by framing the painting in cheesy fake flowers and explosives that diminish its sincerity. Likewise, there’s nothing straightforwardly heroic or the reverse in the appearance of U.S. troops skinny-dipping in a marsh, no uniforms hiding their unique complexions, builds and tattoos. Small text paintings inspired by bathroom graffiti in military camps round out the show, trafficking in disillusioned cliché and acting as foil to the nuances of the portraits that spare judgment and replace dogma with real people.

Originally published in Time Out New York, no 755, March 18-24, 2010.

Liam Gillick at Casey Kaplan Gallery

Liam Gillick’s sculpture, writing and design relate to architectural space, but rarely encourage us to inhabit it, making the seemingly simple addition of benches to his previously debuted overhead sculptures (titled ‘discussion platforms’) a profound development. In a video, Gillick advocates occupation of time, not space, as a means to bring about social change; paradoxically, the new sculpture seems to allow both and relies heavily on the artist’s habitual hope that simple objects will convey complex ideology.

Gillick would be the last artist to purposefully set up binary oppositions, but fundamental incongruities abound, as when the proximity of colorful sculpture makes ordinary benches look beautiful. In the video, we peer over the artist’s shoulder into the dual emptiness of his sterile workspace and his computer screen, where he manipulates an architectural drawing of a factory inspired by a Godard film. The accompanying jargon-filled soundtrack offers a flood of words from the ‘authoritative voice’ Gillick abhors and frustratingly resists any connection to the source material.

In the main gallery, a textual exchange between a quasi time traveler and a contemporary bartender paired with images from medieval woodcuts is more likely to catalyze Gillick’s audience with its provocative blur of time and place. Familiar and strange at the same time, the centuries-old scenes of labor and communal celebration are a puzzle and an exhortation to consider the leisure time we’re enjoying as we sit. Benches – perches of lovers, readers or the homeless – may be less the seats of power than tables or desks, but their identity as temporary resting places is a perfect fit for the in-and-out patterns of gallery visitors and the speculative nature of Gillick’s project.

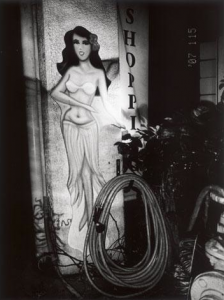

Daido Moriyama at Luhring Augustine

A lone, hunched figure—Van Gogh’s Sorrow draped in a beach towel—opens postwar Japanese photography legend Daido Moriyama’s show about Hawaii, but its brooding mood is misleading. In contrast to a selection of his photos from the ’70s and ’80s in the back gallery, Moriyama’s recent work is literally and figuratively lighter, departing from his trademark rough, blurred and out-of-focus style in a redemptively upbeat portrayal of the islands.

With refreshing honesty, Moriyama doesn’t pretend to be anything other than an outsider, sticking to themes of sun, sand and tourism. Apart from a few shots—weeds engulfing an abandoned car or a hula girl mural in a grubby yard—he’s less interested in exposing life behind the scenes than transforming stereotypical subject matter, which he does with mixed success. A grainy shot of fog rolling in over tropical vegetation and blurred images of palms are nothing new, but a fast-food joint made radically strange by dramatic sunlight or a still close-up of a highly erotic conch shell render the overly familiar strange.

Instead of mounting a critique of crass commercialism, Moriyama portrays tourists as intrinsic to or respectful of the landscape—a kid crawls turtlelike on the beach, and poncho-wearing lava watchers resemble pilgrims—while uncommonly pleasant tourist-shop mannequins portray commerce as low-key. Lest the series come across as too feel-good, Moriyama adds an excremental pile of lava here, a grotesque sunbather there. But with the exception of a kitschy image of a dog wearing sunglasses—a far cry from the artist’s iconic 1971 depiction of a menacing stray—the series’s positive tone is striking evidence of Moriyama’s sensitivity to Hawaii’s mutability.

Originally published in Time Out New York, no 753, March 4-10, 2010.

Virgil Marti at Elizabeth Dee Gallery

Virgil Marti threw a party, but no one showed up. Or so appears his latest decor-as-fine-art installation of wallpapers and furnishings. Chromed mirrors, and anthropomorphized home trappings claiming James Whistler and Chippendale as inspiration, drive home Marti’s recurring theme, that kitsch and excess are two sides of the same coin. But while his show perfectly sets the mood for a high-camp soiree, in the quietly trafficked gallery, it leaves the lingering impression that our invitations must have been lost in the mail.

Not many artists would represent their parents as settees upholstered in flowers, fur and gold lamé (for Mom) or deep blue with black polka dots rimmed in yellow accents (for Dad), as this one does. These fabulously eccentric character studies suggest that Marti is either the secret love child of Liz Taylor and Barry White, or he’s using liberal doses of artistic license to charming effect.

Unfortunately, the seats are off-limits according to a posted sign, sinking the possibility of an impromptu gathering or interaction with strangers. Granted, Marti’s work speaks to the history of objects, but relational aesthetics has us primed to enjoy a coffee and film à la Rirkrit Tiravanija. Frankly, this show could use a little of that, especially since references to role-play, social interaction and posturing seem to run throughout, from the swagged wallpaper (resembling the curtain of an opulent old theater or movie palace) to the hardwood patterns on the mirrors (a reference to treading the boards?). Sadly, allusions to socializing aren’t as compelling as the real thing.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 748, January 28 – February 3, 2010.

William Daniels, “Paintings” at Luhring Augustine

“I thought they’d be bigger!” exclaimed one visitor to William Daniels’s first New York solo show of oil-on-board paintings, none bigger than 13 inches square. In reproductions, Daniels’s images of angular metallic surfaces—mystery objects wrapped in aluminum foil situated within foil-covered sets—grab attention. In person, the seven tiny pieces dotting the walls of the main gallery convey a cheery yet shallow intimacy, evoking shiny candy wrappers or Christmas lights glinting off an ornament.

Despite the bonhomie of pretty hues, Daniels’s subject matter is monotonous, and seesaws between superrealism and lyrical license—a style that’s especially frustrating when the objects are hard to distinguish from their backgrounds and merge into shallow planes of crinkly foil. Eschewing the temptation to depict people or things in reflection—à la Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Wedding, for example—Daniels rejects references to the outside world, creating little hermetic dioramas of light and color, calculated to break boundaries between abstraction and representation, painting and sculpture, by being all at once.

Undoubtedly, this show proves Daniels’s painterly ability and experimental creativity. But unlike his previous meticulously painted reproductions of torn-paper collages sending up or paying homage to canonical art-historical images, the latest work is, unfortunately, literally reflective, and not metaphorically so. The foil covered objects recall John Chamberlain’s twisted auto parts without their bravado, or James Rosenquist’s chrome panels segueing into spaghetti minus the subject matter. Ultimately, while Daniels’s paintings connect with the contemporary fashion for antimonumentality, they have disappointingly little to say.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 748, January 28 – February 3, 2010.

Janine Antoni, “Up Against” at Luhring Augustine

Tied together only by an amazingly adaptable title, Janine Antoni’s new photography, sculpture and installation leap from theme to theme — new motherhood, Hurricane Katrina, a cheeky re-imagining of the female anatomy — in an ad hoc exploration of intimacy and/ or adversity. Though some of her best-known artwork has delved into her relationship with her mother, Antoni is frustratingly ambivalent about her own connection with her young daughter. Ironically, it’s when Antoni herself seems to be acting juvenile, in a piece that has her urinating from the top of the Chrysler Building, that her work is most resonant.

At the gallery entrance, a photo of Antoni’s toddler poking a spoon at her mother’s exposed navel portrays the artist as authority figure, so it’s startling to encounter an image of her using a bronze, shoehorn-shaped gargoyle as a substitute penis to direct a stream of urine in a hilarious piss take of the adolescent male urge to mark territory. Less daring than Margaret Bourke-White’s famous perch atop the Chrysler’s eagles, more restrained than Lynda Benglis’s raunchy posturing, Antoni’s absurd gesture is nevertheless empowering, removing one more obstacle between the sexes.

The show’s final two pieces are less original. A damaged wrecking ball coupled with a close-up projection of an eyeball blinking to resounding booms is a one-dimensional parable of destruction in the blink of an eye and too closely tied to the context of its debut at “Prospect 1” in New Orleans. In a final photo collage, Antoni hovers, spider-like, from a rope web wearing a doll house as skirt, her flesh filling rooms and pressing against tiny furniture in a beautifully succinct illustration of motherly overbearing. But it’s not clear what Antoni’s getting at with the spider reference (and hard not to compare with Louise Bourgeois’s powerful Maman), while the martyr-like pose she strikes doesn’t say anything new about mothers’ sacrifice. We’re extended a tantalizing invitation into the intimacy of her personal experience but come away unenlightened.

Originally published in Flash Art International, no 267, November – December 2009.

Walid Raad, “Scratching on Things I Could Disavow” at Paula Cooper Gallery

The Arab world has recently jumped on the global art bandwagon with a spate of new fairs, biennials and galleries, but Walid Raad is less than enthusiastic. His jam-packed résumé makes him an unlikely candidate to critique the forces of globalization, but surprisingly, this show of new sculpture and work on paper—subtitled “A History of Art in the Arab World/Part I_Volume 1_Chapter 1 (Beirut: 1992–2005)”—cynically argues the powerlessness and conflicted interests of artists.

In text accompanying a sculpture of a miniature exhibition space installed with pint-size versions of his work, Raad asserts that his entire oeuvre mysteriously shrank the moment he agreed to show it in his vast Beirut gallery. The premise is absurd, but the message cautionary: Participation in the system comes at the cost of meaning.

Artists are bypassed as active parties in the exhibit’s two other main pieces. A wall text and photo essay are based on telepathic communication from misguided future artists, who long for an authoritative, editing hand. Elsewhere, a collection of pages from various publications purports to demonstrate the fanciful notion that during the Lebanese wars, compositional elements—color, line, shape—became refugees, hiding in the text and format of various documents and ephemera.

Raad’s critiques are so tangential, his story lines so elaborate, that he doesn’t quite get around to concrete hypotheses on how conflict shapes aesthetics. But if his own resistance is a catalyst for other artists to ignite a new flurry of art activity, one couldn’t hope for more.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 740, December 3-9, 2009.

Nick Mauss at 303 Gallery

For his first solo show at 303, Nick Mauss takes a decisive step away from his best-known earlier work—paintings of dandyish figures adrift in lush fields of color—with minimalist sculpture and stark, etchinglike compositions on silver leaf. Somewhere between an attack on history and self-editing in overdrive, the work makes explicit the frustrations involved in the impulse to communicate.

Though his approach is nearly abstract, Mauss takes pains to invite viewers into his universe. A huge sheet of paper hung to suggest a doorway, then torn open, stands near the gallery entrance, ushering us into the show. Beyond it, a house-shaped framework suspended from the ceiling surrounds a slide projector showing blank slides, continuing the metaphor for transparency but literally and conceptually offering little substance.

Both feel like mere stage setting for the panels, rife with subject matter yielded grudgingly. Because the works are positioned at awkward viewing heights against the gallery wall, it’s easy to miss the occasional vessels, mythological characters or beasts that remain after the artist distressed the surface to reveal a void of black paint under the silver leaf. The vigorous scratch patterns nearly obliterate the sketchy figures, evoking an aura of vandalized archaeological treasures. This subtle attack on icons of ancient art history also recalls Rauschenberg’s erased De Kooning drawing, but Mauss’ idiosyncratic selection of subjects suggests something more personal, like burning a diary or sketchbook. While he doesn’t always strike a proper balance between emulating the past and wanting to eradicate it, his bold marks on delicate panels are an admirably decisive act.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 739, November 26 – December 2, 2009.

Jessica Stockholder, “Flooded Chambers Maid” at Madison Square Park

Jessica Stockholder’s synthetic aesthetic is a strange fit for the beautifully planted Madison Square Park, and her first outdoor installation was a confusing mix of resistance and concessions made to its setting. The alien, saturated colors of a seating platform and set of bleachers took little inspiration from their verdant surroundings. Yet to make this durable furniture for park users, she disappointingly abandoned the improvisatory quality that makes her work so rich. True to Stockholder’s practice of experimenting with unconventional materials, she also created a design in greenery and colorful plastics, but the result is as disjointed and uncommunicative as the installation as a whole.

Among the characteristic sculptures of repurposed consumer goods in her concurrent gallery show at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, a standout assemblage resembled a matronly figure standing before orbs of light on a lawn-like base, making a clever connection between inside and out. But instead of taking the next step and actually engaging the natural world in the outdoor installation, the piece looks ill at ease, its colors and geometries relating less to the park itself than the man-made objects and structures visible on its perimeter.

In what should have been the installation’s focal point, but which was instead a segment of the show half-hidden behind the bleachers, Stockholder attempted a literal combination of nature and culture with a winsome, asymmetrical arrangement of grasses and flowers alongside a too-sparse scattering of man-made materials. The myriad associations that Stockholder can evoke with everyday objects makes her practice compelling; but the banality of this planting suggests we have a more developed relationship with our most commonplace, manufactured junk than with the products of nature. Stockholder’s outdoor debut can leave one wanting to see the artist get back indoors to her studio.

Originally published in Flash Art International, no 268, October 2009.

Sarah Anne Johnson, “House on Fire” at Julie Saul Gallery

There are gaping holes in the shocking story told by Sarah Anne Johnson’s latest sculptures and drawings done on old photos, but the omissions speak volumes. Filtered through the artist’s own childhood memories, as well as first- and secondhand accounts, Johnson revisits the harrowing experience of her late grandmother, Velma Orlikow—one of a group of unwitting patients under the care of a CIA-funded psychiatrist who experimented with brainwashing techniques. Orlikow was subjected to various shock and drug therapies, as well as bouts of prolonged, medically induced sleep. If such a tale can have a lighter side, Johnson looks for it, while also conveying the shattering effects of Orlikow’s ordeal.

Orlikow, who’d originally sought treatment for postpartum depression, plays a starring role in the work, while Johnson’s mother remains an enigma, prompting the question of how the trauma might have passed down through the family. It’s also dubious how Johnson could find a comic element in her grandma’s situation, offering diminutive nude sculptures that depict her with a squirrel’s head or a nuclear cloud blossoming from her skull. (Did Orlikow herself have a sense of humor about what happened?)

Yet an elaborate doll house, which could have been the show’s most lighthearted component, gives sobering insight into Orlikow’s psychological hell, with its hallway going nowhere, foyer under water and melting kitchen walls. While her daughter and husband sleep, Johnson’s grandmother is shown dancing nude in the attic with her doctor, suggesting her sense of vulnerability.

Eventually, Orlikow gave her testimony during a class-action suit that ended in a settlement. Johnson succeeds in adding feeling to those facts with stunning glimpses into the depths of her grandmother’s suffering.

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 734, October 22-28, 2009.

Alessandro Pessoli at Anton Kern Gallery

Though ubiquitous in art history, Christ rarely makes an appearance in Chelsea, meaning that Alessandro Pessoli’s recent paintings of him are surprising for their subject matter alone, not just Jesus haunting weakness. A standoff between a glowing crucifixion at one end of the gallery and a crude portrait of an unruly boy flexing his muscles in mockery at the other sets the scene for a clash between man and God. But the show gets mired in a stumbling uncertainty that there’s any difference between divine and mortal characters.

Pessoli reinvents Christ’s suffering with idiosyncratic symbolism: a body flayed pink or burnt red and a prosthetic arm bearing sunny-colored but sour lemons reinvigorate his identity as the man of sorrows. Pessoli’s indistinct style perfectly captures Christ’s unknowable depth of loss and pain, though certain details—fat, clownish tears; huge, mouselike ears—recall George Condo’s buffoonish caricatures of the Almighty. Pessoli’s portraits aren’t irreverent, however; they afford Christ dignity, just not majesty.

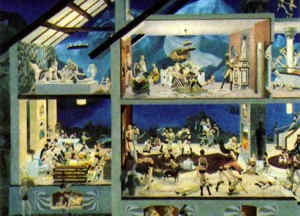

Judging from the show’s other centerpiece—a pessimistic portrait of humanity as presented in a series of small painted sketches—the artist similarly fails to exult God’s crowning creation. Despite being interspersed with panels of gold textile suggesting icons, ghoulish characters with exaggerated features often appear alongside—and overpower—other, more innocuous images of a family, a musician and a runner to create a picture of a corrupt mankind. Paint-encrusted scraps of cloth Pessoli used to clean his brushes accent these vignettes, implying that humans are not the apogee but the castoffs of God’s process. The artist prompts an insincere question: If creation is badly made, who’s to blame?

Originally published in Time Out New York, issue 732, October 8 – 14, 2009.

Phil Collins, When slaves love each other at Tanya Bonakdar

Phil Collins’ ability to find entertainment value in social conflict is stronger than ever in his third New York solo exhibition, in which a soap opera and amateur snapshots become lowbrow delivery mechanisms for universal truths.Soy mi madre, a telenovela-style tale of class struggle steals the show, while a subtler, voyeuristic installation of amateur photos shot by residents of several European cities is a low-key paean to everyday life.Melodrama contrasts the mundane, but each elaborates convincingly on the complexities of human relations.

Soy mi Madre is a tour de force of upper class dysfunction and working class resentment, featuring a pampered lady of the house whose hilariously quick and frequent mood swings are matched by rapid-fire clichés that paint her husband as a lecherous alcoholic and her as mentally fragile, cold and ruthless.By the end, a pistol-wielding servant declares the house’s social order irrevocably changed and one wonders if this video, commissioned by Aspen Art Museum to broaden an audience that includes the area’s immigrant workforce, has the power to alter real life labor relations in ritzy Aspen or beyond.

Free Photolab, a slide projection of selected images by amateur 35mm film users who gave Collins the rights to their images in exchange for free processing, involves exploitation of a softer sort.As photojournalism by proxy, the project provides cheap source material for Collins and more than a few gratuitous glimpses of oddballs or exhibitionists for us.But the collective result – mostly portraits of friends and family at special occasions – has an eerie familiarity echoing common experiences and recalling Nan Goldin’s intimacy, Juergen Teller’s seediness, and Jamel Shabazz’s sassy posers.Several consecutive slides present jarring contrasts (a pregnant belly, then a funeral) but the pictures’ surprising strength is in their poignant take on universal experience.

Originally published in Flash Art International, no 267, July – September, 2009.

“The Generational: Younger Than Jesus” at The New Museum

Auction houses are gravitating towards mature artists and critics have sounded the death knell for the ‘young art star,’ but the New Museum’s first triennial still carries the torch for youth with its showcase of work by fifty international artists, all thirty-three years young or less. If this extravaganza of newness suddenly seems a little out of touch, the show’s curators insist that they’re following the lead of sociologists and marketers in examining the Millennial identity, intending to show it as a generation of producers, not just the consumers they’re made out to be. It falls to one of the generation’s own to honestly portray his contemporaries as consumable; Matt Keegan’s year-book style photo portraits of recent college grads, fresh faced and earnest, tellingly point out that their lives are, as of yet, still largely unlived.