For ‘NYArts’ Magazine

A young woman perches tentatively on the arm of a sofa in her studio apartment, near a poster of Leonardo DiCaprio. She could be any single, young woman just starting out in life. But in fact, as explained in a caption below her picture, she is in the process of selling her home in the Favela Vigario Geral, Rio de Janeiro’s shantytown notorious for military police violence.

This photograph is the first of nearly one hundred that fill the first thirty pages of the catalogue for Documenta11, this summer’s blockbuster exhibition of contemporary art in Kassel, Germany. On page after page, crowds protest, soldiers patrol, and relatives hold up photos of missing or dead loved ones. Photographs, not by artists but by press photographers, from around the world set the tone for the most socially conscious Documenta to date.

Like an aesthetic Amnesty International, the tragic effects of war and bad governance are highlighted in the exhibition halls as well. Artistic director Okwui Enwezor identifies the current age as a, “…turbulent time of unceasing cultural, social and political frictions, transitions, transformations, fissures and global institutional consolidations.” This assessment comes across well in work like Belgian filmmaker Chantal Ackerman’s video on 18 monitors of illegal aliens crossing the U.S./Mexican border, which suggests the difficulty and perhaps futility of patrolling a porous border. Leon Golub’s large-scale paintings of murderous soldiers threatening, “We can disappear you,” are emblematic of corrupt military power. Nearby, a sculptural installation of metal chairs by Doris Salcedo memorializes the wholesale slaughter of a guerilla group by the Columbian government.

Before embarking on what was bound to be a controversial exhibition, Enwezor took two major steps. First, he appointed a team of six international curators. They then organized a series of four discussion ‘platforms,’ international conferences attended by more intellectuals and academics than artists, which began over a year ago. The meetings decentralized the exhibition itself, instead foregrounding debate on topics like the developing nature of democracy or the contrast between judicial justice and truth and reconciliation in countries where enemies must once again live as neighbors.

Although the curators have warned that the exhibition as the fifth platform is not a way of summarizing the first four, there are definite connections between the themes discussed and the work on display. For instance, Isaac Julien’s video “Paradise Omeros” explores the impact of globalism on post-colonial identity and was filmed on St Lucia, the setting for Platform 3, a workshop on Creolization. Likewise, reconciliation, or atonement for past sins, is a strong thematic element in South African artist William Kentridge’s animations. His new video, ‘Zeno Writing,’ tells the story of Zeno’s tortured self-analysis of his politics.

Kentridge is one of several South African artists in the exhibition who respond to the history of apartheid and its legacy. Kendell Geers presents photographs of security warnings on the gates of suburban homes, while Santu Mofokeng’s unpeopled black and white landscape photographs taken on Robben Island personalize the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela. Mofokeng’s photograph of a limestone quarry is echoed elsewhere by an over-the-top installation by Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar. In a darkened room, Jaar presents three texts, one of which describes the damage done to Mandela’s eyes while working in the blinding glare of a limestone quarry. Viewers then walk through two very dark passages that end in a blinding wall of light.

Documenta’s political awareness context casts a new interpretive light on work by several of the show’s best-known artists. Louise Bourgeois’s cruelly caged torsos and dolls push interpretation of her sculpture beyond the usual autobiographical approach. Fellow American Jeff Wall’s ‘Invisible Man,’ a photographed reenactment from Ralph Ellison’s novel by the same name, seems anomalous in Wall’s oeuvre, but no less enjoyable. Similarly, Candida Höfer, the only disciple of German photographers Berndt and Hilla Becher to be included in the show, is represented by her photographs of Rodin’s ‘The Burghers of Calais’, photographed in situ in museums and private collections. The Bechers themselves are represented by two series of photographs featuring half-timbered houses that emphasize the social more than the architectural nature of their chronicling.

Considering how fond the curatorial team seems to be of describing art as a means of ‘knowledge production,’ it should come as no surprise that there is so much documentary video. Indian filmmaker Amar Kanwar’s ‘A Season Outside’ repeats the question, “When is violent resistance right?” in a visually rich video documenting life on the India-Pakistan border. Nearby, Israeli born documentarist Eyal Sivan cut together black and white photographs of Rwanda taken in 1996, two years after the genocide of 800,000 Tutsis.

Less violent, but no less political, Ulrike Ottinger’s filmed trips through Eastern Europe and Western Asia include the one described in ‘South East Passage.’ The demanding length of this 366 minute long video, documenting the people and places encountered on a trip to Odessa, will make it a conceptual artwork for most viewers. Although considerably shorter at 25 minutes, Steve McQueen’s journey into the deepest gold mine in South Africa still required patience on the part of the viewer by virtue of the fact that almost nothing was visible apart from an occasional grainy helmet light flickering across the screen. Similarly slow-paced but absorbing, Zarina Bhimji’s ‘Out of Blue’ slowly moves through the empty houses, barracks and commercial properties abandoned in 1974 when Idi Amin banished Asians from Uganda. Bhimji’s own family fled to the U.K., making this thoughtful video both personally and historically meaningful.

If history is still being written, many of these artists intend to be one of the authors. Fareed Armaly, an American artist with a Lebanese-Palestinian background living in Germany, documents the history of Palestine. For Documenta11, he filled multiple rooms with documentary videos, maps tracking the movement and territory of Palestinians, classic films and postcards following the marketing of Palestinian culture and history for the outside world. Armaly’s collaborative accumulation of historical fact and personal stories is an exhibition unto itself and demonstrates the power of history as a form of protest over current events. His foil is New York based Lebanese artist Walid Ra’ad, who operates under the auspices of The Atlas Group to concoct ironically false historical data about the history of the Middle East. Ra’ad presents the fabricated findings of his fictitious organization, for example, the 29 photo prints supposedly found buried under rubble in Beirut, which allegedly turned out to be portraits of those lost in the Mediterranean Sea during the country’s two decade long war.

The superabundance of text in this exhibition was nowhere more evident than in three large rooms occupied by Allan Sekula’s ‘Fish Story.’ The American artist produced series of photographs and wall texts composed during a five-year investigation of the worldwide shipping industry. From Glasgow to South Korea, Sekula’s worldwide travels tracked a migratory industry and the communities in its wake and in its path. It often seemed that just when art seemed to have totally converted to reportage, an installation or film would inject some pop culture to liven things up again. That was the case with Pierre Huyghe’s ‘Block Party,’ a documentary about the early days of Hip Hop, when its founding fathers tapped current from street lights to power their turntables. The recorded recollections of Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash are the soundtrack to a nostalgic remembrance of Hip Hop before it became a multi-billion dollar industry.

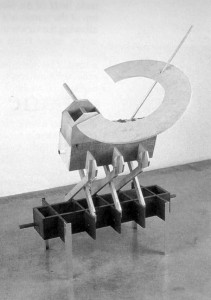

Although it seems like it in retrospect, Documenta11 doesn’t only include video and photography. Architecture in the service of social engineering has witnessed many false starts in this century but makes an appearance in the exhibition. Utopian artists/architects like Yona Friedman and Dutch artist Constant push the possibilities far beyond their realistic potential in several models, paintings and drawings. Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez makes similarly unrealizable, Las Vegas-like fantasy architectural models from product packaging, including a plan for a rebuilt downtown Manhattan. Simparch, a duo of American artists, abandoned tiny models and constructed an indoor, tunnel-like structure in which visitors could sit and enjoy an ambient orchestra of micro-sounds. They also transformed a huge room into a wooden version of a curvy swimming pool for skateboarding, which was enthusiastically being used by local skaters.

In a gesture questioning traditional boundaries of high and low, the exhibition includes documentation of grass roots arts groups like Le Groupe Amos. This group of Christian activists based in Kinshasa, Congo uses visual art, theatre, documentary and radio programs for public education. Similarly, Huit Facettes use the arts to create a bridge between local craft and fine art in rural Senegal. Under the title ‘Park Fiction’, community leaders in Hamburg Germany employed art, film, and theater to stage creative demonstrations against a plan to develop the last remaining waterfront property in their neighborhood. As if the curators anticipated that these community-based projects would be perceived as too removed from work by professional artists, they were segregated in the lounge-like atmosphere of the Documenta-Halle.

Doubtless, Documenta11 will be criticized in the U.S. for including too few American artists, being too preachy and not aesthetically engaging enough. Before the exhibition even began, it seemed unfortunate that the various platforms were staged in locations around the world, making it impossible for most people to attend. However, videos from the conference are available on the Documenta website, providing options (fast forward and rewind) that turn out to make home viewing far more convenient.

With so much text-based work to read and so many hours of video to make time for, Documenta is a difficult exhibition to see quickly. It’s even harder to judge as a whole, for the simple fact that very few people will see all of it. And it can seem dry if learning about fluctuations in the world’s shipping industry is not your idea of an enjoyable day looking at art. In fact, the ‘is it art?’ question is bound to surface, this time in relation to whether many of the projects would have been better realized as history books or entries in a film festival.

Documenta11 often seems to challenge the notion that looking at art should be an enjoyable experience, although anyone familiar with contemporary art knows that visual pleasure is not a pre-requisite. This exhibition steadfastly reminds viewers of that. But after so much art meant for our own good, encounters with more aesthetically pleasing or narrative work were all the more enjoyable. Isaac Julien’s visually lush film ‘Paradise Omeros’ was dizzyingly pleasing to watch. Shirin Neshat’s latest film ‘Tooba,’ set this time in Mexico instead of Morocco, is vintage Neshat – mysteriously abstract and engaging. A confessional video on three screens by Finnish artist Eija-Liisa Ahtila delves into the minds of a young woman with schizophrenic tendencies and a modern day fairy tale by Stan Douglas is like a never ending choose-your-own-adventure story (the piece runs for 100 days without repeating).

At the beginning of this year’s art season, many questioned whether their involvement in the art world had been frivolous, and others proclaimed that art would ‘never be the same again.’ Documenta’s direct engagement with political, economic and cultural globalism puts art in direct relation to current events. As a form of ‘knowledge production’, art has never been more relevant.