For ‘NYArts’ magazine

Is Christine Y. Kim stuck in the shadows, or does she have it made in the shade? Shortly before Kim started her current job as Assistant Curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, curatorial heavyweights Lowry Sims and Thelma Golden moved into the respective roles of Director and Deputy Director/Chief Curator, creating a media fuss and much art world speculation on the institution’s new identity. Golden’s star power attracts a steady stream of media attention and recently made her the subject of a lengthy profile in The New Yorker.

So how is a young curator able to find her own voice in a small museum with two big personalities? Smiling out from the pages of The New York Times ‘Sunday Styles’ photographs last month, Kim didn’t seem to be having much of a problem. The newspaper photos featured the opening of the Museum’s winter exhibitions, the crowning jewel of which is ‘Africaine’, a show of work by four female artists from Africa curated by Kim. At the tender age of 30, she has navigated the competitive world of young curators, to snag a job in one of New York’s most exciting museums, as well as planning independent shows at Artists Space, Gale Gates, and other venues.

‘Africaine’ is the feminine form of ‘African’ in French, and while only one of the featured artists is actually from a country formerly colonized by the French, the title evokes a post-colonial discourse appropriate to the artwork. Kim laughed when I asked about the show’s title, reflecting on someone’s suggestion that ‘Africaine’ might be a new kind of designer drug. Turning serious, Kim explained, “I prefer not to give shows titles that directly locate demographics, race and identity, like ‘Four African Women’, or ‘Nine Korean or Asian-American Artists.’ I like to put the work and the concept of the exhibition before the rest.”

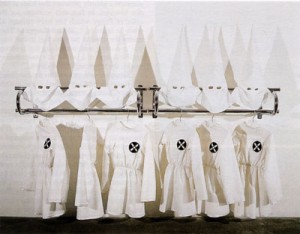

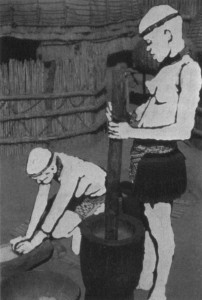

All four artists in ‘Africaine’ grapple with the female form, creating collages or photographs that question how the bodies of African women have been viewed. Twenty-four framed collages of individual women by Wangechi Mutu recall Hannah Hoch’s sexually charged, mixed race collages from the 1920s, while Fatimah Tuggar presents domestic scenes and mixed race couples. Tracey Rose, from South Africa, offers four large photographs featuring herself in the varying roles from porn star Ciccolina to ‘Venus Baartman’ crouching nude in the bush, near the spot where the oldest human remains have been found. Fellow South African Candice Breitz’s images of semi-nude women in tribal dress from 1996 are taken from postcards and transformed by covering the women’s skin with white-out.

Like many people who have a point to make, Kim has a catchphrase. Whether she is referring to Tracey Rose’s provocative photos or the violence of Breitz whiting out black bodies, Kim values ‘pushing the envelope.’ She applies the same phrase to the artists of ‘Purloined,’ the show which opened the ’01-’02 season at Artists Space. All of the participating artists dealt with thievery as a practice or a theme and, as Kim explained, focused on “…challenging the conventions in a community, culture or society.

” Starting with Sophie Calle’s exploits as a nosy chambermaid, the show moved on to look at Polaroids by Lilah Freedland, taken while breaking into the houses and apartments of strangers, and stolen and tagged items presented by Lisa Levy. Other artists, like Nikki Lee and Nancy Hwang, investigated what it means to assume another’s identity. “One of the things that was special about the show for me…” said Artists Space director, Barbara Hunt, “…was Nancy Hwang’s performance where she undertook manicures…You entered through… semi-transparent curtains and sat at table with a sandblasted glass screen, so you couldn’t see the person performing the manicure. She talks about the way in which people really did confess to her and were telling her their secrets five minutes into the manicure.”

As Kim starts to lessen the focus on independent curating and concentrates on her role at the Studio Museum, no doubt she’ll develop her talent for pulling together artists from a variety of backgrounds into tightly themed shows. She is equally interested in artists from the East and West coasts, and says that in her exhibitions, “…most of the time, more than half of the artists are women, more than half are artists of color, but it’s never really mentioned. It’s more about artists working in a certain vein or addressing a pertinent process or idea…” Referring to ‘Africaine’, curator and critic Franklin Sirmans said, “Christine Kim’s approach of mixing up the very local and the global in that show is trademark for her energy in looking everywhere and being able to make the meaningful connections among artists that a lot of people just don’t see.”

Combining the local and global is very Christine Kim. For her next show, tentatively titled ‘Black Belt: Third Arena,’ the curator is planning to explore the conjunction of African-American and Asian-American culture through Kung Fu culture. She points to the popularity of martial arts and eastern spirituality in the African-American communities and is mapping how this has had a significant impact on art by many African-American artists. She is careful to say, “I don’t want to create a narrative that connects Blacks and Asians. But for a generation of people of color strongly influenced by popular culture and urban culture of the seventies and eighties, there was an emergence of another possibility beyond the dichotomies of Black and White from the decade that preceded. There was a transcendent space that mapped spirituality, rebellion, entertainment…and a realization that there were other ‘Americans/Non-Americans’ who perhaps didn’t have exactly the same kind of struggles but experienced social and national alienation whether in the workplace, academic sphere, Hollywood, in sports, or who knows.”

Over the past two years, in addition to working on her own shows, Kim’s assistance to Thelma Golden has provided her with new working strategies. Like others in the field, she uses the word mentor to describe her older colleague, saying “I thought I knew what a mentor was until I met her…It’s not about instruction, it’s about example and about energy.” Kim even admits that her choice of wall color for ‘Africaine’, chartreuse not an earthy ‘African’ color, owes something to Golden.

Far from languishing in the wake of her colleagues, Kim is locating herself as a curator, a second-generation, Korean woman working in Harlem, and a West coaster educated and living on the East Coast. Late one afternoon in February, Kim and I were the last ones left in the museum galleries, when suddenly the lights were turned out. Unfazed, Kim continued talking for another 20 minutes in the dark, enthusing about her ideas for shows and plans as a curator. If the energy of her personality continues to translate onto the walls of her shows, the stars will continue to shine in Harlem.