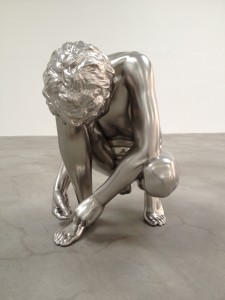

Anish Kapoor’s concave sculptures, like this untitled stainless steel and lacquer disk currently at Chelsea’s Barbara Gladstone Gallery (24th Street location), are austere and elegant, a complete contrast to the lively Gangnam style video he recently released in support of artist/activist Ai Weiwei and Amnesty International. It’s worth another Gangnam parody just to see clips from dancing staff at MoMA, the Whitney, Guggenheim, and Gladstone Gallery and more.