Haim Steinbach’s appropriated Lion King illustration takes over the office wall at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, pitting a powerful creature against box office power against the power of immersion in the color yellow. (In Chelsea through May 27th).

Haim Steinbach’s appropriated Lion King illustration takes over the office wall at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, pitting a powerful creature against box office power against the power of immersion in the color yellow. (In Chelsea through May 27th).

Lucas Blalock’s overt manipulation of this odd but banal scene begs the question of why anyone would want to represent chopped sausage at all, never mind as both a photo and a digital rendering. The effect is to put our minds between places –simultaneously in the digital realm and in a stranger’s kitchen. (At Ramiken Crucible on the Lower East Side through May 22nd).

Water bottles, wiffle balls and even a laundry basket are the among the discarded items artist Marie Lorenz has fished out of New York’s waterways during her boat-journeys-as-art. Here, she has turned them into a ceramic mobile. (At Jack Hanley Gallery on the Lower East Side through May 22nd).

German photographer Elisabeth Hase’s 1931 rooftop photo turns workers and pedestrians into doll-like figures while paralleling the unusual perspectives adopted by Russian avant-garde photographers. (At Robert Mann Gallery through May 7th).

Shot around the world from Peru to Greece, Yorgo Alexopoulos’ videos of the natural world are a low-key sublime, prompting appreciation of beautiful landscapes unblemished by mankind. (At Chelsea’s Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery through June 11th.)

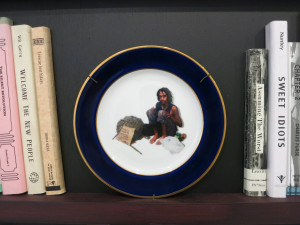

Thousands of books with fake titles create a false and fun library at Pierogi Gallery, where a not-quite-homey feel is completed by Carol K. Brown’s editioned porcelain plate featuring a down-on-his-luck wanderer. (At Pierogi Gallery on the Lower East Side through May 8th).

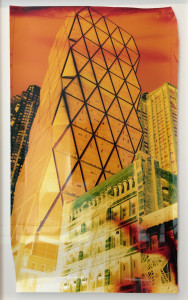

John Chiara’s New York photos – shot with homemade cameras large enough to accommodate big sheets of negative photo paper – bring apocalyptic drama to the city streets. Here, a glowing Hearst Tower hovers menacingly behind a vulnerable-looking walkup as Chiara lends familiar buildings a new character. (At Yossi Milo Gallery in Chelsea through May 21st).

Stay near the wall and the room is silent; approach the table and light sensors detect your presence, setting off a cascade of sound from an array of 72 bare speakers. The effect of Canadian sound artists Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s ‘Experiment in F# Minor’ is magical – a musical experience created for us to create. (In Chelsea at Luhring Augustine Gallery through June 11th).

It’s not the vibrant colors and energetic forms of Shazad Dawood’s ‘Anselm Chapel, Tokyo,’ (seen here in detail) but the strong diagonal lines that connect the London-based artist’s abstract painting on vintage textile with its namesake – Czech/American architect Antonin Raymond’s stark, concrete house of worship. Reconciling opposite appearances seems beside the point with such a joyous composition. (At Jane Lombard Gallery through May 14th).

Gunships approach, bombers fly overhead and the Gemini spacecraft blasts off in old press photos and artist renderings gathered by German photographer Thomas Ruff, now on view in Chelsea at David Zwirner Gallery. Ruff scanned both sides of each photo – all of which relate to the U.S. aeronautics and space program in the 20th century – then merged them to merge private notes and public image. (Through April 30th).

Brazilian artist Adriana Varejao explores the complicated relationship between western and indigenous cultures with a series of self-portraits that blend Native South American and mid-20th century minimalist aesthetics. Here, wavy feathered plumes contrast a stark geometric stripe running the length of her face and clouds of dots over her eyes. (At Lehmann Maupin Gallery on the Lower East Side through June 16th).

They’re not looking at each other, but this dancing couple makes a connection through the eyes. As if they share a common vision, or are alert to each other’s thoughts, each bears an eye of the other as they engage in an elaborate courtship ritual. (At Lower East Side Gallery Thierry Goldberg, through May 1st).

With oppressive systems as his theme, British artist Adam McEwan presents sculptures of supercomputers that move data, a rendition of airport security trays and this walk-in sculpture of the letter ‘K.’ The letter stands in for Kafka and a character in ‘The Trial’ as well as a hieroglyph for an open hand. The most convincing way to understand the mood of the piece, however, is to climb the terrifyingly steep stairs. (At Petzel Gallery through April 30th).

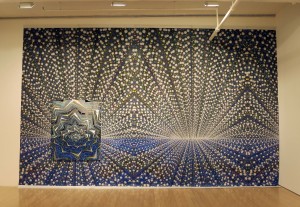

Set against wallpaper developed for an installation at Mass MoCA, Barbara Takenaga’s ‘Life’ looks like an implosion inside of a molecular structure. The effect is eye-popping in person. (At DC Moore Gallery in Chelsea through April 30th).

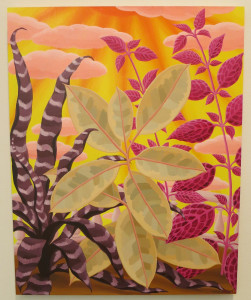

New York artist Amy Lincoln carefully studies particular plants, then incorporates them in paintings of the natural world so crisp and vibrantly colored, they’re almost hallucinogenic. (At Morgan Lehman Gallery in Chelsea through May 7th).

Arranged in vitrines or along this long shelf, Katy Fischer’s ceramic objects look like archaeological finds. They’re a humorous take on the notion that ceramics must have use-value and yet provocative in prompting consideration of what those uses might be. (At Lower East Side gallery Louis B. James through May 1st).

Painter and sculptor Volker Hueller is known for mining art history, remixing styles and associations from yesteryear into a contemporary visual vocabulary. In this recent painting, on view at Lower East Side gallery 11R, he turns one of his signature, geometric characters into art object, suggestively equating face and vase. (Through April 24th).

Above a barely noticeable landscape of frothing waves and neon-colored bridges, a strange assortment of alien characters array themselves like a contemporary, psychedelic thangka in Keiichi Tanaami’s ‘Vision in the Womb.’ The Japanese icon blends eroticism and the lingering terror of Tokyo’s firebombing in a hallucinatory scene that stuns in its creative profusion. (At Chelsea’s Sikkema Jenkins & Co through April 23rd).

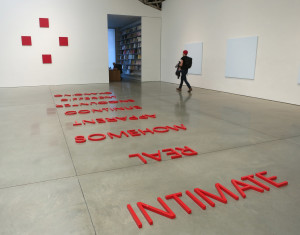

Conceptual art pioneer Robert Barry uses language to transport viewers; in this handsome installation, cast resin letters painted a vibrant red form words like ‘intimate,’ ‘apparent’ that evoke strong associations. (At Chelsea’s Mary Boone Gallery through April 23rd).

Using her home and the surrounding landscape in Amagansett as subject matter, Jennifer Bartlett offers two versions of the same view. Both have been constructed with a graining brush, a tool that allows her to paint in parallel lines, taking her longstanding relationship with the grid to new directions. (At Paula Cooper Gallery through April 23rd).

A visit to the Alhambra in Spain inspired Oxford, England-based Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi to begin his ‘Flamenco’ series, in which he celebrates the music and dance of Andalusia in his signature, modernist style. (At Salon94 on the Lower East Side through April 18th).

Though they’re both solitary women illuminated by glowing backgrounds, the subject of Barkley L. Hendrick’s 2015 painting, Anthem, couldn’t be further in character from the measured cool of his iconic 1969 ‘Lawdy Mama.’ This singer is holding nothing back as she takes the stage with a double mike and unrestrained self-confidence. (At Jack Shainman Gallery through April 23rd.)

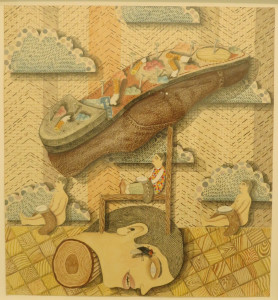

You won’t find wholesome fantasies of life in the American heartland in Iowan artist Timothy Wehrle’s surreal pencil drawings at Chelsea’s P.P.O.W. Gallery. Under rain clouds, a severed head acts as momento mori, while an upside down shoe studded with nails suggests a painful journey. (Through April 16th).

Young Johannesburg artist Serge Alain Nitegeka pushes abstraction off the wall at Marianne Boesky Gallery in Chelsea, altering the gallery with paintings that project into the room while simultaneously acting as portals into 2D illusionary spaces. (Through April 23rd).

Evocative sculpture by New York artist Sarah Braman creates a nexus between mass produced furniture and the unique art object, coldly minimal forms and a potentially cozy bedroom, a mined metal and unexploited nature in the form of a gorgeous sunset. (At Chelsea’s Mitchell-Innes & Nash through April 16th).

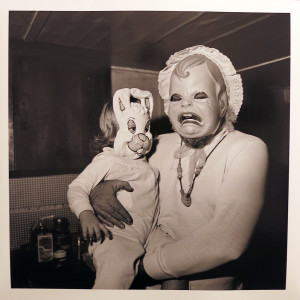

This shot by Rosalind Fox Solomon comes across as simple enough at first…until you register that the caregiver is a crybaby, caring for a bunny and wearing a beard, defying expectations at every turn. The unexpected and odd dominate Fox Solomon’s selection of images from her archive, shot over three decades and around the world, now on view at Bruce Silverstein Gallery in Chelsea. (Through April 16th).

Fruity filling oozes from cracked dough like blood seeping from a wound in this painting of two stacked donuts by Emily Eveleth. The painting’s title ‘Façade,’ suggests we’re only getting half of the story and backs up the impression that these donuts can be read as stand-ins for much more. (At Danese Corey Gallery in Chelsea through April 16th).

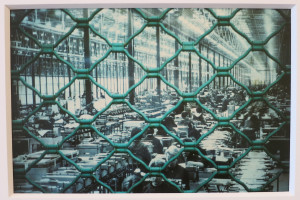

A series of charming vintage color photos from the 70s and 80s by the late Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri, currently on view in Chelsea at Matthew Marks Gallery, use framing and balance to tell stories. This photo – cropped or layered to hide how a fancifully colored turquoise grate came to stand between us and a huge factory floor – both keeps us out and the workers in. (Through April 30th).

Mary Weatherford’s Casa Reef is a standout in Skarstedt Gallery’s excellent painting show in Chelsea, bringing to mind Yves Klein’s body prints, but in geometric blocks that suggest an underwater structure emerging from swirling white foam pushed by a (literal, neon) current. (In Chelsea through April 16th).

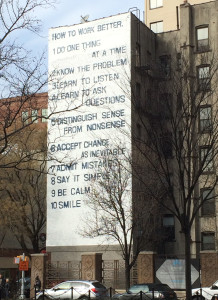

Since lifting it from the bulletin board of a Thai ceramic factory 30 years ago, Swiss artists Fischli and Weiss have reproduced this motivational list in different locations and formats over the years, most recently installing it on Houston Street in Manhattan. From the simple instruction to ‘do one thing at a time’ to the more profound challenge to ‘distinguish sense from nonsense,’ the advice encapsulates the artists’ credo to ask questions and embrace the absurd. (On Houston St at Mott Street through May 1st. For more info, see Public Art Fund or visit the artists’ retrospective at the Guggenheim.)

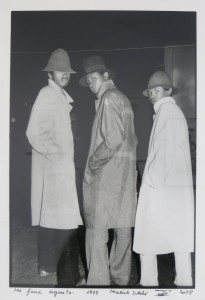

Iconic photographer Malick Sidibe – who will be 80 this year – pulls out more joie de vivre from his famous archives of Malian night-life with images shot at parties over the decades. Here, three young men dressed as secret agents let us in on the fun of their masquerade. (At Chelsea’s Jack Shainman Gallery through April 23rd).

Haegue Yang continues her ‘Trustworthy’ series – made from the patterned interiors of security envelopes – with this installation of abstract diagrams set against deeply soothing Yves Klein blue walls at Greene Naftali Gallery. Just as Klein offered a portal into the sublime, Yang points to the mystical with her eye-like shapes and totemic figure covered in bells. (In Chelsea through April 16th).

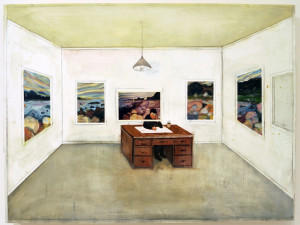

A moody beach scene by Norwegian expressionist icon Edvard Munch inspires this painting by William Wegman at Sperone Westwater Gallery, which incorporates and builds on a postcard at center. Wegman both adds psychological intensity and humor to Munch’s angsty scene by making the main character a creative type alone in his Spartan room. Come see this painting and more on Saturday’s Lower East Side Gallery Tour, 1 – 3pm. (Click here for tickets. On view through April 23rd).

Fractal patterns on the walls of meticulously constructed dioramas by French artist Laetitia Soulier at Claire Oliver Gallery transform each space into a fantastical realm. The dominant cube pattern in this construction leaps off the walls and into the ever-decreasing form of this Lilliputian set of nesting rooms. (In Chelsea through April 9th).

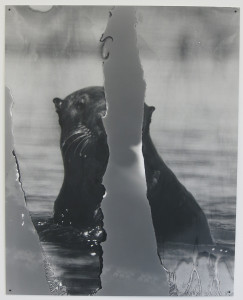

Her own nature photography and images downloaded from the Internet are the basis for several new photos by Eileen Quinlan at Miguel Abreu Gallery, including this interrupted shot of an otter. A strip from the center of the image looks like both a rip and a pool of water, while streams of photo chemicals toward the bottom of the image contrast liquids used in photo processing with the otter’s natural habitat. (On the Lower East Side through April 17th).

Celebrated Cuban artist Roberto Diago presents wall-mounted works in corrugated sheet metal that look like weather-beaten modernist abstractions with a distinctly Cuban twist revealed in the title, ‘Variaciones de Oggun,’ a nod to the Latin American deity Oggun, who is associated with metal work. (At Magnan Metz in Chelsea through April 9th).

Inspired by Artemisia Gentileschi’s famous early 17th century painting of the Biblical heroine Judith slaying the Assyrian army general Holofernes, Anna Ostoya’s quasi-cubist rendition of the scene pits Judith against herself. Now that beheadings have become current events, Ostoya asks to what extent this is self-definition and self-harm. (At Bortolami Gallery in Chelsea through April 23rd.)

Tim Hawkinson offers visitors to Pace Gallery the chance to snoop through his medicine cabinet, in the process giving us the time around the globe with what’s actually a world clock in disguise. The unassuming bathroom fixture includes a bandage representing the time in Los Angeles and a soap pump acting as a clock for Tokyo. The biggest delight is New York’s timepiece – a lotion bottle with a cap that rotates as an hour hand and a drip of lotion (plastic) that acts as the minute hand. (At Chelsea’s Pace Gallery through April 23rd).

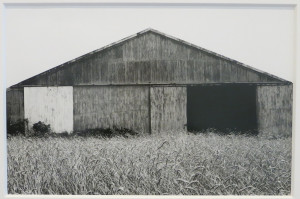

Strong shadows and angular forms in photos of barns and rural architecture shot between the 50s and early 80s by Ellsworth Kelly bear a striking resemblance to the abstract shapes of the artist’s paintings, offering what feels like a peek at the artist’s real-world inspirations. (At Matthew Marks Gallery in Chelsea through April 30th).

Doug Fogelson’s ‘Ceaseless’ series comprises beautiful but damaged nature photos, for which the Chicago-based artist shot traditional landscape photos, which he printed and partially destroyed by applying common industrial chemicals to the surface. Ironically, the results are gorgeous. Here, a verdant forest hovers like an apparition surrounded by peeling layers of emulsion. (At Sasha Wolf Gallery on the Lower East Side through April 16th).

Iconic appropriation artist Sherrie Levine pairs monochrome paintings replicating colors found in Renoir’s nudes with colorful SMEG refrigerators in groupings that might serve to remind or warn snacking art collectors of Renoir’s voluptuous figures. (At David Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea through April 2nd).

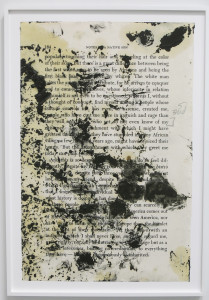

Glenn Ligon turns his well-worn copy of James Baldwin’s 1953 essay, ‘Stranger in the Village,’ into a suite of prints, each more or less obscured by paint and fingerprints left behind by years of reference use in Ligon’s studio. Ligon’s marks testify to the personal importance of Baldwin’s text, while the parts that remain visible leap out as a kind of charged concrete poetry. (At Luhring Augustine through April 2nd).

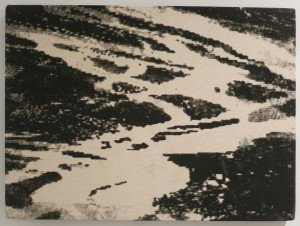

It would trouble some, but the smell of burning paper is the norm in Chris McCaw’s photographic practice. Using powerful lenses, McCaw magnifies the intensity of the sun to the extent that it burns holes in the light sensitive paper he places in his homemade cameras. The effect is ethereal, as the sun literally carves a path through the sky over shadowy landscapes. (At Yossi Milo Gallery in Chelsea through April 9th).

Mark Dion’s latest show is for the birds, which is to say that the centerpiece, a huge cage housing a selection of books related to birds and their predators along with several zebra finch and canaries, is intended as a gift to our feathered friends. The birds seem to be more concerned about nest building and communicating with each other than in reading, leaving the literature to humans and reinforcing Dion’s point that it’s always about us. (At Tanya Bonakdar Gallery through April 16th).

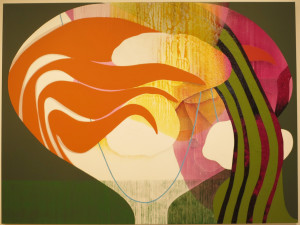

“It’s not about being a commodity, it’s about the pleasurable experience of looking,” explained Carrie Moyer to an interviewer recently, elaborating on how her once overtly political art practice has morphed into a subtle advocacy for enjoyment. (At DC Moore Gallery through March 26th).

In Walid Raad’s tongue in cheek narratives about the emergence of a booming new Arab art world, he’s hunted for refugee color and fonts that have gone into hiding and reflections that are missing; here at Paula Cooper Gallery, a wall text explains that the shadows normally cast by the artwork have run away, no longer interested in being part of the art infrastructure. The artist hopefully builds a series of walls with fake shadows to entice the real ones to return, all the while ostensibly failing to notice that the art itself is missing. (In Chelsea through March 26th).

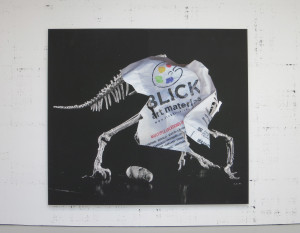

David Zwirner Gallery’s normally pristine white walls look as though they’ve been damaged by scraping; a closer look reveals that black markings are text fragments, printed onto posters that cover the walls of Michael Riedel’s latest solo show. Known for recycling text and image from his previous shows, Riedel takes the metaphor a step further by picturing animated dinosaur skeletons, creatures whose lives have been extended, in a sense, by being exhumed and put into the public realm again. (In Chelsea through March 25th).

Inventive use of materials is everything in Karla Black’s huge installation, ‘Includes Use’ at David Zwirner Gallery. Mixing powder paint and plaster, Black covers the gallery floor with a beach of cocoa-like powder separated into curving organic shapes by frilly tucks of toilet paper. The artist resists the term ‘feminine’ to describe her work, but with glitter as the finishing touch, the effect is decidedly pretty. (In Chelsea through March 26th).

Colorful lumps of squeezed clay, or the pattern on a checked shirt are inspiration to Houston-based artist Jeremy Deprez; here, he presents visitors to Feuer/Mesler Gallery with a five foot high bar of hotel soap. Unlike pop predecessors who supersized everything from hamburgers (Oldenberg) to soup cans (Warhol), Deprez pays painterly attention to his flecked monochrome. (On the Lower East Side through March 27th).

Toothbrushes hang in neat rows, labeled with the names of patients at a now-closed psychiatric hospital in Poughkeepsie in this arresting photograph by Christopher Payne. Payne traveled to hospitals around the country over several years, creating a moving document of life in a bygone era. (At Chelsea’s Benrubi Gallery through March 26th).

A flood of frogs (vinyl silhouttes adhered to walls and floor) escape down a fake drain in Brazilian artist Regina Silveira’s space-bending installation at Alexander Gray Associates. Referencing Biblical plagues and unexpected, underground activity, the frogs suggest that above-ground life is only half of the story. (In Chelsea through March 26th.)

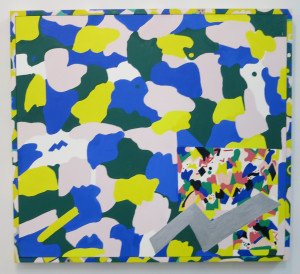

A painting is set into a painting, set into a painted frame in Nora Griffin’s ‘Painting Culture,’ a nestled presentation of homey organic shapes, cheery color and unselfconsciously handmade marks that conjures 80s design and a kind of youthful freedom exemplified by a zany silver zigzag. (At Louis B. James on the Lower East Side through March 20th).

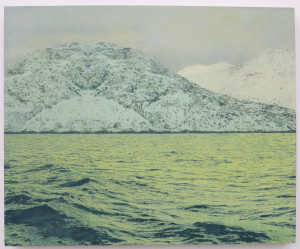

A trip to the Arctic inspired Saul Becker’s uncanny landscapes, in which mirrored hills present a Rorschach for those wishing to ponder lesser known regions and toxic colors bear witness the changing climate. (At Zieher Smith and Horton in Chelsea through March 19th).

The bar below his apartment, the 99 Cent Pizza place, the Laundromat and apartment furnishings inspired New York artist Nicholas Buffon’s latest paper sculptures, what the New Yorker called, ‘elegies to a vanishing downtown.’ Here, even his stove and cheerily decorated fridge bespeak the well worn and well loved. (At Callicoon Fine Arts on the Lower East Side through March 20th).

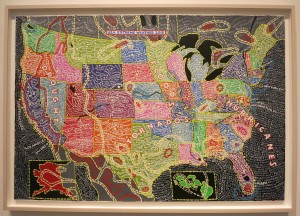

Paula Scher, principle at renowned design firm Pentagram, invites us to understand the country through its airline routes, geography, climate and here, its weather. Her painted maps of the USA emphasize how we see places through frameworks of information. (At Chelsea’s Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery through March 26th).

A 300 lb piece of talc was the basis of this large sculpture by Larry Bamburg, who bridged the natural and manmade by adding a similarly colored soap, then bathroom tiles to the stone, creating a conversation between materials whose properties converge yet remain distinct. (At Simone Subal on the Lower East Side through March 20th).

Inspired by late Renaissance and Baroque landscape painting, tapestry and stage scenery, Karen Kilimnik’s latest body of work showcases interiors with canopied beds and manicured landscapes, stage-like in their perfection. The exception is this expressionist tropical landscape with its sumptuous, glittery tent, as lush as the greenery. (At 303 Gallery in Chelsea through March 26th).

David Kennedy Cutler continues to turn photographed or scanned images into provocative sculpture with a cluster of heads representing Bacchus – the god of wine and related merrymaking – grouped together like giant grapes. Paired with slices of bread, however, does the reference turns toward the Eucharist? (At Lyles and King on the Lower East Side through March 13th).

Innocuous floral arrangements in archival photos of historically important business and political meetings inspired New York artist Tayrn Simon’s latest project, ‘Paperwork and the Will of Capital.’ With a botanist’s help, she recreated bouquets present at shady dealings – when Mozambique agreed with South African not to support the ANC in the 80s, or when business owners purchased citizenship in St Kitts in return for supporting economic development there. She then entombed photos, texts and specimens in a concrete press, which acts here as a pedestal. (At Gagosian Gallery, through March 26th).

Casey Ruble’s meticulous cut paper images of former safe houses on the Underground Railway and locations of Civil Rights era riots confer a potent stillness on historical scenes that are fading from memory, largely unmarked by signage or physical markers. Here, she focuses on the epicenter of the 1967 Newark riot, where police mistreatment of an African American cab driver sparked a devastating protest. (At Foley Gallery on the Lower East Side through March 20th).

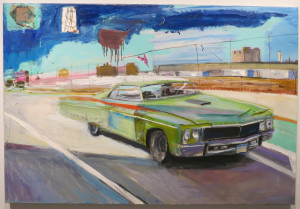

Under a darkening sky, a classic car speeds along an elevated city highway under a dollar sign and two maps of the US in this painting by Matt Blackwell. In the car, a bearded man with gritted teeth (succinctly crafted from a scrap of plaid fabric) grips the steering wheel, seemingly on a lone mission of intense urgency. (At Edward Thorp Gallery in Chelsea through March 19th).

Matt Blackwell, Going Out West, oil on canvas with collage, 44 x 64.5 inches, 2015.

Using techniques from ‘how to’ TV shows on painting, British artist Neil Raitt makes odd juxtapositions of cabins and mountains, cacti and palm trees in repeating patterns that are like digital wallpaper but carefully hand-rendered. (At Nicelle Beauchene Gallery on the Lower East Side through March 13th).

Titled ‘Trips I’ve Never Been On,’ Shara Hughes’ solo show at Marlborough Gallery includes slightly surreal scenarios like this one, a juxtaposition of landscapes that seems both dream-like and real. (In Chelsea through March 12th).

From sounds recorded at a textile factory in Bally, PA and computer data sites, Mika Tajima and a textile designer worked to translate sound waves into visual patterns. Old technology – the mill uses jacquard looms (a punch-card system invented in the early 1800s) – meets new in a beautiful abstract textile that looks like a screen interrupted by interference. (At 11R Gallery on the Lower East Side through March 13th).

Since 1993, Richard Dupont has made silkscreens from photos of TV screens with scrambled signals. The results look like paintings of lassos of paint, actual paint skeins, abstract expressionism or a capture of paranormal activity. (At Tracy Williams, Ltd. through March 6th).

Flesh-color, cabbage-like leaves nestle in a container that recalls an incubator in Hannah Levy’s alluringly odd sculpture at 247365 Gallery. Waxy fingers that hold the tub and leaves made of something resembling skin recall Keith Edmier’s resin renderings of his mother or Matthew Barney’s plastics and petroleum jelly, making for fascinating but unnerving sculpture.

Sally Saul’s arresting ceramic self-portrait portrays her as if in mid-sentence, her eyes looking into the distance as if trying to phrase something just so. Surrounded by tiny attentive birds, what she says has caused nature to stop and listen. (At LaunchF18 on the Lower East Side through March 6th).

This small painting by New York artist Clare Grill is a standout in a group show at Lower East Side gallery Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects for its lively color and suggestion of a sympathetic face framed by lighter color, curving bands. (Through March 13th).

Like Freud, Mickalene Thomas’ couch has made her famous. Normally appearing as a colorful, patchworked backdrop in Thomas’ photos and paintings of lounging African-American beauties (seen on the back wall), it’s a character of its own in this retro living room, transplanted to Chelsea’s Aperture Foundation. (Through March 17th).

At over ten feet tall, this polyethylene sculpture by Jeff Koons magnifies kitsch to its limits. Whether it’s a contemporary crucifixion, as Koons has said, a phallic symbol, as others have pointed out, or something else entirely, there’s more than meets the eye. (At Chelsea’s Flag Foundation through May 14th).

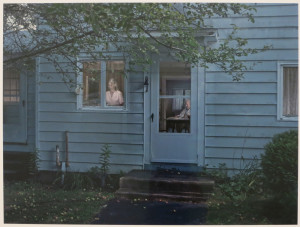

The color and lighting of Gregory Crewdson’s new photos can be traced to his interest in how painters of the 19th century and prior drew viewers into their paintings with detail and tones that could be appreciated from both near and far. The photos’ suspenseful and melancholy mood might be attributable to major life changes, which have included a new gallery, a divorce and a move out of New York. (At Gagosian Gallery’s 21st Street location through March 5th).

In person, the subjects of LA painter Vanessa Prager’s heavily painted portraits only faintly emerge from their textured backgrounds; in photos, they materialize more readily. The implications of being more visible on a screen aren’t lost on Prager, who has installed peep-holes through out the gallery to carry on a conversation about the absence and presence of images today. (At The Hole NYC on the Lower East Side through Feb 29th).

Photographer Chris Killip’s iconic images of the North of England, shot between 1973 and 1985, give meaning to the stereotype, ‘It’s grim up north.’ How will these two young girls survive their grey surroundings? (At Yossi Milo Gallery in Chelsea, through Feb 27th).

“I don’t care about beauty at all,” New York painter Amy Sillman has declared about the imperfect figures and heavily worked canvas of her paintings. Recent works at Sikkema Jenkins & Co are titled after the German word for metabolism, a nod to the process of changing paint into images that land provocatively between abstraction and figuration, suggesting both bodies and furniture in a color palette that simultaneously soothes and excites. (In Chelsea through March 12th).

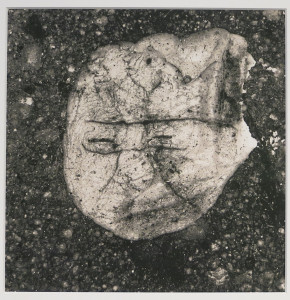

From the 1940s onward, the fashion world embraced the elegance of iconic photographer Irving Penn’s highly visible commercial work, but it sometimes took longer for his personal projects to gain traction. In the iPhone era, his investigation of the wonderful in the banal seems prescient, especially in this particularly charming shot of an eerily face-like wad of chewing gum found on the city street. (At Chelsea’s Pace Gallery through March 5th).

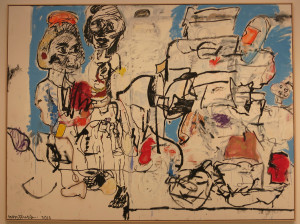

Eddie Martinez continues to mine art history in increasingly abstract paintings now on view in Chelsea at Mitchell-Innes and Nash. Tapping into diverse sources of inspiration – from Basquiat’s jittery line to de Kooning’s boldly outlined bodily forms – Martinez creates strangely familiar paintings to ponder. (Through March 5th).

My first stop at this year’s Armory Show (New York’s 4 day art fair extravaganza on Hudson River Piers 92 and 94) was the new WSJ Media Lounge – a spacious theater offering respite from the milling crowds and endless white cubicles. Inside, Danish artist group ‘Osloo’ offered up possibilities for what they call “public spiritualism” through music and lectures, as they did last summer for their national pavilion at the 2011 Venice Biennial aboard their floating platform. It wasn’t clear where the spiritualism lay, but the vibe was definitely not commercialism – a palpable contrast to what lay beyond the lounge.

Performance – both on and off the official program – was in evidence here and there, notably in Marina Abramovic’s ‘Bed for Human Use,’ in which a woman in a lab-coat lay prone on an uncomfortable looking bed face-to-face with a chunk of quartz crystal at Sao Paulo’s Luciana Brito Galeria.

Over in Armory Focus: The Nordic Countries, curious onlookers watched as a young woman sitting on a fur rug in front of a mini-teepee stapled canvas to a stretcher in the light of pentagram at Stockholm’s Fruit and Flower Deli. Meanwhile, front and center in Italy/China/France–based Galleria Continua was a vast mirror by Michelangelo Pistoletto which seemed like a tempting invitation for narcissistic visitors to put on a show of their own.

Armory Show Commissioned Artist Theaster Gates wasn’t manning his Pier 94 Café installation of school chairs and desks rescued from a Chicago school, designed to be a place for him to ‘hold court.’ But in nearby Chicago/Berlin gallery Kavi Gupta’s space, Gates’ white concrete rectangular columns, glass and wood cubes and section of framed chalkboard also evoked missing kids and teachers, leaving the history and future of the school where he sourced his materials an open and worrying question.

And speaking of missing, Michael Riedel’s installation at New York’s David Zwirner’s booth was easy to miss, but worth checking out. Wallpapering one end wall was an image that appeared to be a reflection of the rest of the booth – three simple, large silkscreens – making for a daringly ephemeral installation in one of the Show’s prime spots.

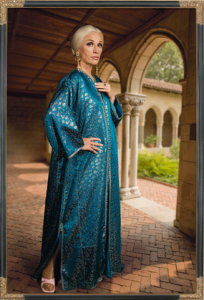

The biggest surprise in Cindy Sherman’s major career retrospective, opening to previews today (and officially on Feb 26th) at the Museum of Modern Art, is that there are few surprises. It testifies to Sherman’s stature and influence that so much of the work in the show – 171 photos from the 1977-80 Untitled Film stills to the most recent send-ups of society matrons – is so familiar that it’s hard to even find the critical distance to reconsider it.

What does emerge is Sherman’s consistent and merciless pillorying of character types from the fashion victim to the aging coquette in galleries arranged by series – history portraits, centerfolds, etc – or by theme – fashion, carnival, abjection. By comparison, the Untitled Film Stills (appearing in their entirety) appear kind by virtue of their hidden fakery and purposefully glamorized subjects.

Grotesquery – not limited to the fairy tale or sex series – is a heavy component of most of the work, whether in the repellent muscles of a prosthetic cleavage or the big hair and garish makeup of a woman trying desperately to hang on to her looks. Sherman’s caricatures let most of us off the hook – at least until we start wearing caftans to lounge around our loggias – by representing ‘other people’ who’ve lost their style compass.

Sherman’s early work – seen at the beginning and end of the show – belies such distancing, specifically a stop motion animated short film depicting Sherman as a paper doll who selects her own outfit only to be returned to her case by a giant hand. The artist’s ‘hand of God’ is now aided by Photoshop, as she alters facial details like those on an 18 foot high mural at the gallery entrance. But though technology lends Sherman the potential for serious distortion, she holds back, continuing to tweek the conventions of dress and representation to which we adhere to a greater or lesser degree.

Can a museum exhibition claiming to “embrace the energy of this generation’s (international artists in their 20s and 30s) urgencies” compete with still fresh images and reports of Arab Spring or Occupy Wall Street protests? While socially aware, The New Museum’s second Triennial, ‘The Ungovernables’ demonstrates less of a radical edge than a persistent questioning of the status quo and power structures in artists’ home countries around the world. More of a chipping away than an uprising, for better or worse the show largely dispenses with aesthetic pleasure or craftsmanship in favor of often personal engagements with broader cultural or national identities.

The standouts include:

Hassan Khan, b. ’75, lives Cairo. Jewel, ’10 – This mesmerizing video choreographing a two-man dance-off in traditional Cairo style is the show-stopper.

Cinthia Marcelle, b. 74, Brazil. The Century, ’11 – Barrels, hardhats and more objects are hurled down a street in a video orchestrated by Marcelle, offering some of that talked about urgency and exciting the senses but without reference to any particular conflict.

The Propeller Group, founded 2006, Ho Chi Minh City. TVC Communism, ’11 – On a circle of five monitors, five ad execs from an international agency hired by the Group hash out the intricacies of rebranding Communism, a fascinating conjuncture between competing ideologies.

Pilvi Takala, b. 81, lives Amsterdam and Istanbul. The Trainee, ’08 – For a month, Takala posed as an intern at an accounting firm raising the ire of fellow workers as she sat motionless at a desk or rode the elevator. Their irritation seems to be the point, and while this illumination of social and workplace expectations yields results that are hardly surprising, it’s an amusing scenario for us, especially when Takala tells chagrined employees that she’s ‘working in her head.’

Jose Antonio Vega Macotela, b. ’80, lives Amsterdam, Mexico City. Time Divisa ’10 – Over a four-year period, Vega Macotela exchanged labor with Mexico City prison inmates, completing agreed upon assignments simultaneous that included smuggling in items in return for a map showing the route that 100,000 pesos took inside the prison.

Slavs and Tatars, founded 2006, Eurasia. Prayway, ‘12 – A communal, ‘riverbed’ seat by the collective Slavs and Tatars appears to be an enormous folded sheet of metal resembling an open (prayer) book with a Persian rug arranged on top and a blue neon glow beneath – a Star-Trek channeling exercise in incongruity that should get conversation started.

Relational aesthetics took a beating last fall as critics decried participatory artworks like Carsten Holler’s three story slide at the New Museum and MoMA’s installation of Rirkrit Tiravanija’s free lunch. The visitor’s physical experience is also key to Doug Wheeler’s installation which opened today at David Zwirner Gallery and recreates a 1975 piece made in Milan by the influential So Cal ‘Light and Space’ artist. But the hushed environment, limited to ten people at a time and entered after donning white booties so as to keep the floor pristine, is all about aesthetics, and less about interrelating with your fellow gallery goers.

The lighting in the installation changes in intensity and color as it simulates the transitions from dawn to day to dusk, slowly revealing where the boundaries of the flat floored, egg-shaped room are. But even in the strongest light, it’s a strain to make out where gallery wall ends and floor begins; only the toes can tell as you feel the floor’s upward slope. The impulse is to find the spot where your senses are most confused.

Visitors who stayed in the gallery the longest this morning inched their way to the front and center of the installation and stood looking into an optical illusion – a space that appeared to extend to infinity. The sensation was like peering into a deep fog or a snowstorm (under comfortable conditions) as my perception of space kept shifting to make sense of what I was seeing.

Wheeler’s installation recalls James Turrell’s installations, in which visitors approach a shape on the wall only to realize that it’s a rectangle of recessed light. Here, the experience is more intimate – like entering into the space occupied by light rather than gazing in from the outside. Uta Barth’s photographs of light come to mind, as do Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Nets but both treat light and infinity as more concrete subjects than Wheeler does with what he calls his ‘molecular mist.’ The scale and ambition of Wheeler’s project won’t be matched again soon in New York; catch it while you can and arrive early to avoid lines.

For more background, read Randy Kennedy’s Jan 15th NYT article.

Image credit: © P.A.R. Photo by Marc Domage

Picasso may be one of the 20th century’s most influential artists, but the jury is still out on the value of his late works. ‘Mosqueteros,’ an exhibition of nearly one hundred paintings and etchings at Chelsea’s Gagosian Gallery is the first major U.S. effort since a 1984 Guggenheim show to change the prevailing perception that the late master had lost his touch by the time of his death at age 91 in 1973.

In a great blast of energy, Picasso spent the final years of his life creating hundreds of paintings after canonical works by Velasquez, Goya, Delacroix and other old masters. Adapting images of soldiers, prostitutes and performers to his trademark, fragmented and twisted style, Picasso seemed to be grappling with his own position in art history. At the same time, the works’ title, ‘Mosqueteros,’ or musketeers, referred to the non-paying rabble at the theater and hinted at the artist’s status as an onlooker as contemporary art rejected abstraction.

Response to the Guggenheim show was underwhelming. New York Times critic Michael Brenson praised Picasso’s energy more than the work itself, while the less gracious Robert Hughes opined that the work showed only fragments of Picasso’s talent.

So why try to change the record now? John Richardson, curator of this show and Picasso’s biographer, says he’s ‘avenging’ Picasso of the poor response to his work; more interesting to a contemporary art audience, he also explains that he intends the artist to, “…look like a brand new painter.”

Portraits like Buste (1970), a character whose feline face is created with pools of dark paint punctuated by a phallic or key-like orange monocle, immediately make the case for Picasso as a forerunner (albeit distant and far more dignified) to young, expressionist-inspired artists like Jonathan Meese and Andre Butzer. Though the character’s terrible, black-eyed gaze ties him to Picasso’s other harrowing portraits, Picasso eschews the sketchy outlines he uses in many of the show’s other works, and composes using blocks of color in a style that enhances the mystery of his shadowy personality.

In 1984, Hughes noted the speed with which Picasso painted, and condemned the artist for making his painting process more important than the final product. Nowadays, that’s accepted practice in any media, from Josh Smith’s paintings, to Fia Backstrom’s performance/installation work to Walead Beshty’s photography and sculpture.

Picasso’s late paintings aren’t likely to be direct precedent for any of these artists. But given the popularity of mining 20th century avant-garde art history (think camera-less photography, constructivism, 60s and 70s performance), it’s fascinating to see evidence of the reverse process – a canonical artist who seems to have deliberately pointed several ways forward. As evidence that he was a wellspring of ideas until the end, this exhibition will doubtless have the legacy-effecting impact it deserves.

In recent boom times, some dealers and artists were accused of catering too much to the demands of the market. So will the recession mean more adventurous, less sellable artwork? If Dario Robleto’s solo exhibition at D’Amelio Terras’ booth at this week’s ADAA Art Show is any indication, dealers will just find ways to be even more sales savvy.

Robleto’s meticulously crafted sculptures, constructed from materials like audiotape on which recordings have been made or 19th century ‘hair flowers’ made from the hair of loved ones, represent personal stories to those in the know. In addition to six new pieces at the Art Show, Robleto is offering a “unique commissionable sculpture” titled “Love Survives the Death of Cells,” for which couples will record their heartbeats, which will be transferred to audiotape that will be stretched into hair-like strands and braided together to create a Victorian style keepsake.

Maybe it’s the proximity of the fair and the commission offering to Valentine’s Day, but the ‘sculptures’ sound more like luxury gift item than artwork. I could be a sucker for a romantic gesture, but is this the quality of artwork appropriate for one of the most prestigious art fairs in the country? As portraiture, the pieces won’t represent individuals, as multiples, they signify little, instead promising to come across as tchotchkes by an otherwise uniquely inventive artist.

You don’t have to make it to Chelsea to see New York’s hottest shows this month. Peter Doig’s first New York solo show in a decade takes place on the Upper East Side at Michael Werner Gallery and in the West Village at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise where new canvases feature ping-pong players, human moths and mysterious landscapes.

Also on the painting front, South African artist Marlene Dumas’ figurative paintings in her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art are dark but arresting. Critics from the LA Times Christopher Knight to the New York Times Roberta Smith point out the prominent pros and cons of the show, and it’s easy to walk through and create your own checklist of art historical references, not an unrewarding task.

Nevermind the global financial turmoil (finally starting to be reflected in the art market), a bevy of new Chelsea gallery shows are making November and December good months for gallery goers. At 303 Gallery, Anne Chu – who New York Times critic Roberta Smith called “one of the best figurative sculptors around” – has toned down the aggressive style that once led her to make Tang Dynasty style ladies with chainsaw and wood, but the results of her more conceptual approach are still a must-see.

Meanwhile, splash and burn painter Barnaby Furnas opens his fourth solo show at Marianne Boesky Gallery with distressed canvases loaded with poured and splattered paint. His long-running portrait series of Civil War abolitionist John Brown is starting to wear thin and the outraged political caricatures from his last show are unfortunately no where to be seen. But abstracted images of spot lit rock concerts and ‘black flood’ paintings are provocatively discordant mixtures of pleasure and disaster.

On the same block, don’t miss Cindy Sherman’s gargantuan new photos of herself in the guise of various aging society matrons at Metro Pictures. Glitzed up and surrounded by markers of status, these ladies will no doubt look mighty familiar to many of the art community’s power lunching gallery hoppers.

October is the perfect month for gallery visits, when the season is back in full swing and great weather makes it irresistible to get out and see what’s new. Among the best shows is Doug Aitken’s latest solo at both locations of 303 Gallery, where the mesmerizing video ‘Migration,’ stars American migratory animals confined in rooms at a series of down-at-the-heel motels. A bison knocking down chairs, a deer sipping from the pool and beaver in the bathtub suggest that animals can survive our encroachment – but can we? Speaking of animal nature, Cecily Brown is back with more paintings exploring her signature subject matter – sex. The act is discernable in a few canvases but most are abstract, allowing viewers to make their own conclusions about where her writhing brushstrokes take us. Ernesto Neto’s social spaces are decidedly more public. For his sixth solo show at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, a cave resembling a giant caterpillar takes up residence on the ground floor while upstairs, architectural maquettes allow visitors even more intimacy with the artist’s ideas for the space around us.

Video art may be notorious for not selling as well as other media, but several Chelsea galleries are having a moment with the medium this month. Miami-based Luis Gispert delivers the weirdest show in a dual appearance at Zach Feuer Gallery and Mary Boone Gallery with an enormous projection featuring the gruesome exploits of a libidinous butcher. At the opposite extreme, Israeli artist Guy Ben-Ner’s videos at Postmasters Gallery starring the artist and his two super-cute children thankfully manage to be more amusing than saccharine. Those looking for intellectual challenge can check out ‘the royal game’ embodied by Diana Thater’s chess matches at David Zwirner, or for ‘the beautiful game,’ visit Greene Naftali Gallery and see German filmmaker Harun Farocki’s twelve screen compilation of footage and analysis of the 2006 World Cup. And no video tour through Chelsea would be complete without stopping at Iran-born video art legend Shirin Neshat’s latest videos and photos at Barbara Gladstone Gallery.

For dates of shows and gallery locations, visit Zach Feuer Gallery, Mary Boone Gallery, Postmasters, David Zwirner, GreeneNaftali and Barbara Gladstone Gallery.

Sexually, politically or aesthetically provocative contemporary art is easy to find, but true controversy is rare. For nearly a decade, Kara Walker’s artwork has excited loud response – both enthusiastic and horrified – and is bound to generate even more discussion now that her highly anticipated survey exhibition ‘My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love,’ is open at the Whitney Museum. Pilloried by many African American artists in the late 90s for trafficking in negative black imagery, Walker’s signature installations of black-paper silhouettes on white walls, drawings, projections and texts mine America’s past and present race relations in all their ugly complexity. If you gravitate towards art that demands a personal response from its audience, this is the hottest show in town.

For more information, visit the Whitney Museum’s website:

If you weren’t already aware of Richard Serra as one of the country’s most respected sculptors, you will be after taking in his forty-year career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA actually accounted for the requirements of Serra’s enormous sculptures in its recent rebuilding and renovation, a fact which underlines his esteemed reputation and makes for a stunning installation in the 2nd floor contemporary art galleries and sculpture garden. The show’s 550 tons of undulating steel sculpture include three new pieces as well as iconic favorites, making it not only one of the most anticipated shows of recent years, but the hottest show of the summer.

This month, the exhibition mostly likely to get people talking earns its ‘hottest show’ tag by literally applying the heat to gallery visitors. As part of an installation, artist Rirkrit Tiravanija, his assistants, staff at David Zwirner Gallery, or volunteers are preparing daily vats of feisty Thai curry to which visitors can help themselves. Dealers, critics and art world luminaries have been spotted indulging in a spicy lunch at tables and chairs scattered around a plywood structure which replicates 303 Gallery’s space in Soho, where the piece was first exhibited in 1992. Tiravanija reveals his indebtedness to Gordon Matta-Clark’s precedent-setting café, ‘Food’ and his unconventional use of real estate by sharing the gallery space with a recreation of Matta-Clark’s ‘Open House,’ a sculpture made in a dumpster which coincidently occupied the same SoHo address as Tiravanija’s exhibition when it was created in 1972.

For more information, visit David Zwirner Gallery’s website.

Just can’t get enough Picasso! No less than three major New York museum exhibitions currently feature the art master, arguing for his allegiance to historical Spanish painting (Spanish Painting from El Greco to Picasso at the Guggenheim), identifying his influence on American art (Picasso and American Art at the Whitney Museum) and his importance to one of the early 20th century’s greatest art dealers (Cezanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde at the Metropolitan Museum of Art). Factor in the extensive permanent collection display of the artist’s work at MoMA, and this could be one of the city’s biggest Picasso moments in recent history.

Find out more on the following museum websites: Guggenheim Museum, The Whitney Museum of American Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

What do you get when you mix a hot art star, Hollywood luminaries including Tilda Swinton and Donald Sutherland, and the exterior walls of the sleek, midtown Museum of Modern Art? A highly visible, super-stylish art video in the form of Doug Aitken’s seven screen projection, Sleepwalkers, which began screening nightly outside MoMA in mid-January. Times critic Roberta Smith concisely summarized the effect as “dazzling and a bit bloodless.” But considering that New York magazine anticipated this to be the “most seen show in MoMA’s history,” and the fact that the museum reported over two and a half million visitors last year, that’s a huge audience for Aitken’s film, without a doubt making it the hottest show in town. (Sleepwalkers screens nightly at MoMA from 5pm – 10pm until February 12th.)

See the trailer and visit the on-line exhibition on MoMA’s website:

Two shows vie for the title of ‘most talked about’ this month: young, German maverick John Bock’s new video and zany rooftop installation at Anton Kern Gallery and painter of curvaceous women, Lisa Yuskavage’s latest bevy of babes at David Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea and Zwirner & Wirth uptown. Those who love Bock’s signature mad scientist behavior will delight to find the provocateur slithering through cabinetry, eating from a can of ravioli with a spoon attached to a chair leg and performing other bizarre feats. Likewise, Yuskavage fans will enjoy a spectacular array of light drenched, color-soaked portraits of fecund females. Neither will leave you short of conversation. (John Bock is at Anton Kern Gallery until November 25, Lisa Yuskavage’s paintings are up until November 18.)

After an August lull, the art world has suddenly come to life with hundreds of new exhibitions opening within the first three weeks of September. With so much competition, it’s hard to single out a solitary, ‘best’ show, although a few stand out primarily because of their spectacular new surroundings. Powerhouse dealer Marianne Boesky’s new building on 24th Street houses Barnaby Furnace’s enormous paintings depicting the parting of the Red Sea, while solo shows by John McCracken, Jockum Nordstrom, and Yutaka Sone inaugurate David Zwirner’s new empire of art galleries (three in a row) on 19th Street. (Barnaby Furnace’s show runs Sept 16 – October 21. John McCracken’s and Jockum Nordstrom’s shows are open Sept 8 – October 14th and Yutaka Sone’s is open Sept 21 – Oct 28.)

Read more on the following gallery websites:

Marrianne Boesky Gallery

David Zwirner

Every summer, galleries showcase their finest talent with group exhibitions of work by their artists, and every year the standout shows are those that have gone the extra mile with creative themes and new artists. The current offerings include a lively sampling of work by young Rio de Janeiro artists at Daniel Reich Gallery, ‘I’m Yours Now’ a selection of artwork created directly on the gallery walls at Sikkema Jenkins, and a quirky exhibition at Andrew Kreps Gallery for which one artist invited another to participate, who invited one other artist and so on. The only problem? There’s so much to see. (Through mid-August)

Read more on the following gallery websites: Daniel Reich Gallery, Sikkema Jenkins Co, Andrew Kreps Gallery

Wangechi Mutu’s exhibition of violently beautiful collages could be one of New York’s most anticipated solo show debuts ever. After receiving rave reviews for her participation in what seems like endless group shows around New York over the past few years, the Kenyan-born Mutu is having the dramatic coming out, with a dual show at Sikkema Jenkins and swanky uptown gallery Salon 94. Come see for yourself what all the chatter is about.

Read my profile of Mutu’s work from Art On Paper, Summer 2004.