For ‘Flash Art’ magazine

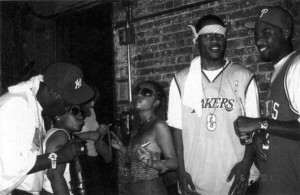

Yo, peep this out. Supa fly artist Nikki S. Lee is takin’ over da city this month with photographs of Hip Hop’s dopest scenes. Nikki throws down some bustin’ new work at The Bronx Museum and in her solo show at dealer Leslie Tonkonow, plus showing highlights from the past four years in “Purloined” at Artist’s Space. The ‘Hip Hop’ project is Lee’s latest series of photographs, taken as she hung out with newfound friends on the New York Hip Hop scene. In work that is half photography, half performance, Lee is an outsider giving her audience the inside view of Hip Hop culture.

Last summer, Lee was sponsored by the Bronx Museum to create work now on show at “One Planet Under a Groove”, an exhibition examining the connections between art and Hip Hop. Her trademark way of working is to radically transform her physical appearance in order to look like a member of various communities, including punks, skaters, senior citizens, and yuppies. She researches each group extensively and learns the skills necessary to fit in, in one case getting sponsorship to cover a gym membership to tone her body, and at another time, spending weeks in Riverside Park learning to skateboard. In the Hip Hop project, Lee closely imitated styles of dress, makeup and hair popular in the Hip Hop community and spent hours in a tanning salon to darken her skin. In the resulting photographs, Lee works the dance floor, pouts at the camera and just hangs out with a crowd that includes music producers and graffiti artists.

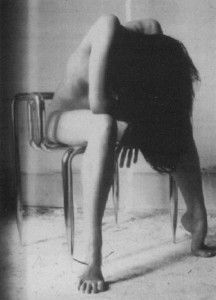

Although she studied and practiced commercial photography for the better part of a decade, Lee adopts a hands off approach to the camera. Instead, she asks friends and onlookers to take snapshots of her as she hangs out with her crowd. In the same way that she relinquishes control of the camera, she embarks on her performance projects uncertain of the outcome. In last year’s Exotic Dancers project, in which Lee applied for and got a job as a topless dancer in a nightclub in suburban Connecticut, she worked in platform shoes, garters and not much else. Before this, she created the Lesbian project, in which she is seen sharing intimate kisses with an accommodating blond. In both projects, Lee left her comfort zones far behind, taking risks that give her work strength as performance art.

On a superficial level, Nikki Lee seems to be acting out the American immigrant experience – trying on different aspects of the new culture to see what she’ll take or leave. The fact that she emigrated to the U.S. from Korea only seven years ago makes it all the more surprising that she has been able to master the details of so many subcultures in so short a time. But her forays into individual and group identity are even more profound considering Korea’s conflicts over national identity in the last century. A divided country, recovery from the attempted annihilation of the Korean culture and language by Japanese colonialists, and rapid urbanization and industrialization have put ‘traditional’ Korean folk culture in sharp contrast to modern city life. Anti-American sentiment at home, particularly with regard to U.S. military forces in Korea, makes the position of a Korean immigrant in the U.S. all the more meaningful.

Although fractured identity is fundamental in Lee’s photographs, Leslie Tonkonow points out that, “…One thing people misunderstand about Nikki’s work is that even though it touches on issues of multiculturalism, cultural identity and cultural politics in the United States, this is not really her issue…She is approaching these series very much as someone who is Asian and who has an Asian perspective on the individual in the group…” Lee has made it clear that she is focusing on the way in which any individual will define him or her self in relation to a group while contrasting the pursuit of individual identity in the West with the Asian orientation towards group identity. In an interview earlier this year, she told ICA Boston assistant curator Gilbert Vicario, “…In my work, I take pictures with a group and with other people of the group. So I describe like-people and their cultures, and then it goes back to my identity: I describe myself.”

Lee foregrounds the question of her identity by making artwork which resists a story line. Usually, her pictures look like she is just ‘hanging out’ on a normal day with her normal friends. Often compared to Cindy Sherman or Nan Goldin, Lee denies that either artist has substantially influenced her. She tells Vicario that her work is, “…not about Nan Goldin’s work, you know, going from bathroom to bedroom. Go to your house and look at your snapshot album. You don’t have pictures of sex scenes. Most people only have snapshots when they go traveling.”

Her extreme travels into foreign cultural and racial territory have produced images of subtle incongruity. In gesture, makeup and clothing she plays her parts perfectly, but her Asian features give her away every time, resulting in an initially confused reading. With an ‘anything is possible in New York’ attitude, it is feasible that a young, Asian-American woman might be a swinger, yuppie, lesbian or punk. But it is when she steps across racial barriers that questions of identity and not just subcultures come to the fore, and she creates her strongest work.

Because there is little suggestion of narrative in her photos of group life, the work has the feel of documentary. However, Lee subverts the expectation that the ‘reality’ of each group will be faithfully captured by the camera by the simple fact of her presence in each shot. Like the current trend for ‘reality’ programming on TV, the audience knows that the situations are heavily manipulated and the actions of the characters are influenced by their setting. Lee engages the demand for manipulated reality with work that revels in the contradictions of the global culture. By suggesting that Western viewers consider themselves as part of communities, not total free agents, the artist proposes an alternative way of conceptualizing life and community. She also offers an antidote to the isolation of modern, urban culture.