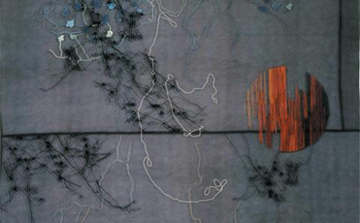

Violet Hopkins‘ latest paintings won’t blow your mind, but her subject matter might. A hand holding a frog, a spiraling shell and more seemingly random subjects are actually based on photographs encoded on a solid-gold laser disc sent into space aboard on the 1977 Voyager mission as a primer to life on Earth for anyone out there who might be interested. Thirty years on, with interest in aliens confined mostly to the movies and economic concerns trumping the cosmos, Hopkin’s project neatly summarizes the current national psyche while posing the question of how one would create such a summary today.

With their fuzzy photorealism and drab palette, Hopkin’s small ink and pencil paintings redirect attention from themselves to Voyager’s impossibly ambitious aim of depicting everyone and everyplace. The show’s two largest works acknowledge the daunting nature of the task: A close-up of an eye reflecting a solar eclipse represents a quintessentially awesome experience which should actually blind its subject, while a rendering of the instructional diagram inscribed on the golden record looks undecipherable. The landscapes and portraits in the show, along with two ‘indexes’ – gridded images showing the vast variety of human achievement – would be of little use to E.T., but are uncomfortably revealing nonetheless, especially in our security-conscious times.

While the country may be more inwardly focused now than three decades ago, Hopkins, at least, gives us a chuckle with one image here of a groovy 70s landscape painter working in his chalet-style studio. Dated stereotypes aside, her project acknowledges art’s challenge to interact with a vast, ever-changing world.