For ‘NYArts’ Magazine

With its energetic urban aesthetic and a roll call of hot young artists, ‘One Planet Under a Groove: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art’ at the Bronx Museum is one of the best group shows of the year. Co-curator Franklin Sirmans is primarily known for nearly a decade of art writing, but with ‘One Planet’ he has begun to seriously flex his curatorial muscle. Talking as easily about Hip Hop as High Modernism, Sirmans has made it his trademark to write about young contemporary artists who have arrived in New York on the wave of globalism. In December, he curated ‘Rumors of War’, the inaugural show at new uptown space Triple Candy and at the same time, put together an exhibition room for Fast Fwd: Miami focusing on utilitarian art. Merrily Kerr talks to Sirmans about ‘One Planet’ and a new generation of artists.

MK – You’ve done more writing and editing than curating. Do you consider yourself more of a writer than a curator?

FS – Definitely. But the approach is always similar…putting together a small show is a lot like writing a big essay. For me personally, most of the thought process is developed first in writing anyway….But I am very happy writing; that was the way it began. I wasn’t an artist, I wasn’t trying to be an art historian per se, it was about writing about art and using art as a vehicle to talk about so many issues.

MK – Several of your exhibitions have been about urban culture. The latest shows have had titles like “Classic Works of Urban Culture”, “Pavement,” “New York, New York”…

FS – That is a central part of where I find myself right now. In fact, Adam Matthews and I are working on a book of memoirs which is basically about recollections of youth spent outside of the urban environment and about how the necessity for dialogue leads people to these centers – New York, London, Paris….We worked on a story together for ‘One World Magazine’, in which I wrote this piece about Harlem. I grew up in this building here [points out the window to building next door]. But it’s about going away and coming back and talking about the changes that have occurred.

MK – Yeah, because you lived in Connecticut when you did your degree at Wesleyan, you studied at Morehouse College in Atlanta and later lived in Milan for two years.

FS – Coming back here after the cracked out ‘80s…and now there are galleries…it’s crazy. I had one week where I did three or four reviews without going below 96th Street. It was fantastic.

MK – Let me ask you about ‘One Planet Under a Groove’. How did you come up with the title?

FS – We [Sirmans and Bronx Museum Curator, Lydia Yee] bounced ideas off of each other and came up with that, and it resonated. On the one hand there is a reference to Parliament and to Funk, which is such an integral part of where Hip Hop came from. You can’t talk about Outkast without knowing about P-Funk. It comes up in Adrian Piper’s work and in other people’s work…As opposed to George Clinton writing ‘One Nation Under a Groove’, at this point in the way we looked at the show, we could safely say ‘One Planet Under a Groove,’ referring to the music.

MK – It’s ‘One Planet’ because the artists are coming from different backgrounds and countries?

FS – Yes. Japan, Italy, Korea. It was weird how the Asian influence is so much more prevalent than say, a European one. Like Hisashi Tenmyouya’s work– it’s like Wu Tang but from a Japanese perspective. There is a dialogue. And to look at Nikki Lee’s work and the ideas that she is questioning…Her work makes a lot of people uneasy.

MK – Can you summarize your essay in the ‘One Planet’ catalogue?

FS – We all have a silly blind faith that visual art is removed from all those other systems of mass media. And it was talking about that – what a great place to start. Hip Hop. The images being sold on MTV and how they can be detrimental in many ways. I was interested in talking about where the initial impulse is, where is the essence of the product? Is it about this ‘bling bling’ thing that has developed? Of course not. And how do we look at the ideas that we are giving to children, in particular? Artists are the ones who challenge these things.

MK – Like Susan Smith – Pinelo’s gyrating females in the video ‘Cake’?

FS – That’s why I love her work. It’s basic but totally powerful. In the catalogue essay, I wanted to try to grab people with a language that was not normally confined to the art exhibition catalogue. I started the essay by talking about Jay-Z. The line he uses is, “I’m overcharging niggas for what they did to the Cold Crush.” Cold Crush being one of the first Hip Hop groups who got no love and put out amazing songs, didn’t make any money, and now they’re trying to get their own little piece. They’re going to put out their own independent label record now. They were coming straight from the initial impulse of the art form. Until you have that market and you have all those people working into the machinery its just sitting there. So I was trying to make some distinction between the craft and the commodity, which I have been trying to do about visual art for some time.

MK – So are you saying that an artist or group of artists innovates and then a whole other group of artists responds and a market grows around it? We now have a commercially successful generation of young artists who have come out of the Freestyle show at the Studio Museum in Harlem last summer. In one of your review of Mark Bradford’s show at Lombard-Fried, you said that there was lottery draft for these artists amongst New York galleries.

FS – Totally – Rico Gatson, Mark Bradford, and Julie Mehretu…I know I’m missing somebody. That’s three artists with openings in the same week….Places like The Studio Museum in Harlem and now The Project make it possible for me to do what I do. I think what that gallery has done has changed a lot of things. What kick started it, it seems to me, was that it was about things that were happening outside of New York. If you look at a lot of the artists he [Christian Haye] shows, it is so easy to look at the work and say, ‘Wow, this is damn good work, and no one in New York is showing it.’ It still blows my mind that there aren’t more galleries that at least have somewhat similar aesthetics. Being in Europe from 1996-98 was really important for me. In 1997, Harold Szeeman did Lyon, he did a show in Slovenia. Johannesburg happened. Venice was that year as well. And all these shows brought together an exciting mix of artists. Someone from New York would not have done those shows. Because we know that we are the center of the world….and sometimes if it is not in front of our face then it can’t be that good, we seem to say.

MK – The term ‘post-black’ came out of Freestyle. Do you think this is a useful term?

FS – It sparked a hell of a lot of debate and dialogue, and that’s useful….Thelma Golden is definitely someone who has been amazingly important to me. Still is. And doing the Hip Hop show, there were elements that we had to be very conscious of from the Black Male show….It is a very, very different show, but we were conscious of it. For me, it was a marker. That ‘93 Whitney Biennial, her show in ’95 and the international biennials in ’97. Those are really, really important markers just like Freestyle has been.

MK – I tend to think that you write about African and African-American artists – but you write about all kinds of people. Was my initial perception right or wrong?

FS – Perhaps…I’ve studied African-American artists, my father is an avid collector, and my first experiences with art were with black artists, people like Ed Clark, Romare Bearden, Vincent Smith, Jacob Lawrence. I grew up with that. So it is a base, but I certainly don’t seek to limit the artists that I am talking about. It also depends on what you read. I’ve had people who have seen certain pieces, like maybe a Robert Ryman piece or a Sol LeWitt piece they I’ve written and they’ll say, ‘Oh, I thought you were white.’ People are funny like that.

MK – How would you write about Mark Bradford without modernism as a base?

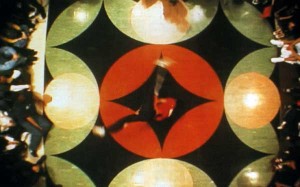

FS – You can’t. But it certainly helps to know something about black vernacular if you want to talk about Mark. A lot of the investigations into modernism have a certain resonance for artists. Like the way that Janine Antoni brought this consciously feminist-based presence to minimalism. ‘Gnaw’ is a brilliant piece. I think that is what Juan Capistran is doing with his piece. Break dancing on top of a Carl Andre – some interesting things happened when he mixed things up. He actually went into the museum and did that piece while a friend kept the guard away.

MK – Do you have an ideal exhibition?

FS – [Laughs] Give me lots of money to pay every artist a fee up front…that would be fantastic! But there is no ideal space. I don’t know if there is an ideal show. I’d like to do small, one-person exhibitions in addition to other group exhibitions. I want to do a group exhibition called “A Hero Ain’t Nothing But a Sandwich.” The title comes from a book by Alice Childress that was made into a film in 1977. On one hand, it has this resonance for me growing up. On the other hand, it’s got that idea that we were talking about with Capistran and Carl Andre or like Janine Antoni with ‘Gnaw’. Art and modernist art history makes these big, gigantic heroes. It’s trying to talk about that and perhaps bring that lofty idealism down a little bit, and look at the work for what it is as opposed to this idea of the grand heroic – the mark, the gesture. Come on!