Francesca Woodman changes from girl to woman within seconds in the first two pictures displayed in her retrospective exhibition at the Guggenheim: first we meet a fresh-faced kid wearing a billowy flower-patterned tunic and her signature Mary Janes, making a motion as if she’s holding a clapper board and about to shout ‘action.’ Next, we see her nude lower body coming from a cupboard, the tilting camera catching her as if in a fugitive act. Taken in her freshman year at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1975-6, the precocious Woodman already explores the signature themes of her short career – non-narrative scenarios in which her young, perfect body interacts with the crumbling architecture of a Providence house or an old warehouse-like space in Rome (during her Junior year abroad).

Whether she’s lying curled up on old floorboards under a heavy wooden door propped precariously against the wall or straddling an old fireplace mantle leaning against the wall, Woodman attempts impossible hiding acts that ironically expose her to both prying eyes and the danger of falling props (in later pictures, we see a snake slithering across her outstretched arm and threat arrives again in the form of a wasp on her neck).

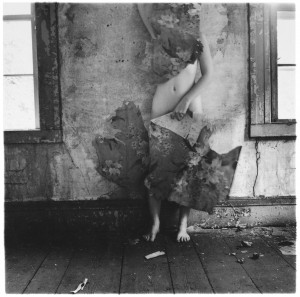

Her interaction with the space of the dilapidated room she’s in (in one, a view out the window shows a presentable house next door) resonates with Gordon Matta Clark’s radical interventions in abandoned or otherwise neglected spaces. But Woodman’s nude or partly clothed body (looking very unlikely to have ripped a door from its hinges or detached a mantel) forces unlikely connections with domestic space rather than destroying it. In one image, she covers herself modestly at breast and pubic area with two jagged sections of ripped wallpaper that cover her face and create a flattening of space that merges her body with the wall.

Using her body and physical surroundings as materials, Woodman aligns with late 70s conceptual art and body art contexts in the show’s most surprising images, such as one alarmingly masochistic image showing her at close range with clothespins attached to her nipples and abdomen. Whether this is a larger comment on womens’ bodies or sexual behavior, references to sexuality are rare, despite her frequent nudity. So much so, in fact, that when a’79-‘80 image cropped to exclude her head shows her clutching three sizeable zucchini, the allusion is so out of place that it’s more funny than it might be in another context. Later, she poses in a jeweled belt or dons multiple garter belts like an overdecorated Bellocq model, but the photos feature her curves more as formal compositions than critiques or self-exploration.

In three pictures, Woodmans lets a man into her mostly solitary, female world. All titled, ‘Charlie the Model’ they feature a heavyset man clothed, crouching nude while peering in a mirror, and smiling through a circular glass while a nude Woodman moves in a blur behind him. Perhaps because of his size or his smiles, he dominates, which put viewers in mind of his personality rather than Woodman’s retiring character and emphasizes how her more characteristic images don’t really aim to explore identity. The closest to narrative or role-play she comes is in an early photo series (exhibited in an easy-to-overlook passageway between galleries) titled, ‘Portrait of a Reputation,’ a five-image artist book from 1976 in which Woodman poses with hand over her heart, with or without clothing and with the outline of her hand eventually degenerating into two handprints suggesting an assault.

It’s a Woodman moment in New York now, with a show of the artist’s late work at Marian Goodman Gallery and the monumental ‘Blueprint for a Temple’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s contemporary photo galleries. Woodman appeared to be in a transitional stage when she took her own life in 1981 at the age of 22, making larger images and experimenting with blueprinting processes and collaged images. In ‘Zig Zag’ from 1980, she creates a zigging and zagging line by linking photos of bent arms, v-shaped dress backs, scissoring legs, and more expanding her subject matter to include other people while still exploring the body and pursing formal relationships in her art. Cruelly, seeing so much of her work whets the appetite for more, but true to the Guggenheim’s purpose, offers opportunity to reconsider the context for photography in late 70s America.