- Yun-Fei Ji at his drafting table, courtesy Yun-Fei Ji and James Cohan Gallery

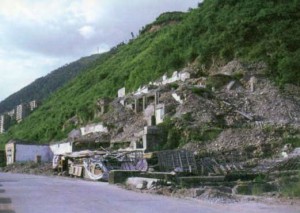

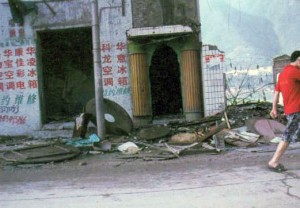

Yun-Fei Ji’s monumental new landscape paintings, depicting scenes along the winding banks of the Yangtze River just prior to the area’s flooding by the Three Gorges Dam, are composed of imagery sampled from a vast archive of photographs, notes and sketches he has developed on several trips to China over the past five years. In the paintings, day laborers, moving trucks and departing residents occupy the cities and villages amid tranquil, mountainous scenery. The inclusion of fantastical characters and otherworldly scenarios distances the delicate ink on paper paintings from pure documentary. Still, the volume of primary research behind each image is in and of itself highly significant.

Before Ji made his first research trip to the Three Gorges region in 2001, he investigated the area’s rich history and turbulent politics, delving into its literature, following news reports, and reading blogs detailing often tragic stories about locals affected by the dam project. During his travels, he amassed tens of thousands of images and reams of notes, which he organizes by geographic location upon returning to his studio, storing the digital photographs on CDs and filing away clippings and other ephemera. Although he has no routine habit of accessing his archive (and sheepishly admits to sometimes losing track of what he’s collected), for the latest series, Ji dug back through his images in search of the period before the flood. “In each picture, I can point out a detail that interested me,” he says. The photographs in Ji’s archive depict a wide range of subjects, among them tidily stacked building materials, doors and windows waiting to be taken and reused, scavenging day laborers and the ubiquitous camps of holdout residents who refuse to move until the last minute.

Ji draws from computer printouts or while looking at photos on his monitor, improvising as much as he copies. “I’m not just adding things up when I work,” he says. “I find details that trigger my interest and imagination and act as a stepping point to something else.” Ji’s sketches can also originate just as easily from an idea generated during a conversation, from a found photograph, or, from other found source materials. In one case, a propagandist magazine cover from the 1950s showing happy farmers in a time of widespread famine inspired an etching of cadaverous landsmen, while in another, accumulated tales from the demolition workers resulted in a painting of a scavenger’s wife communing with the dead.

“There is almost nothing that I don’t draw,” says Ji, referring both to the large number of drawings that cover the walls of his studio and fill his sketchbooks and to their varied subject matter, from studies of plant life to half demolished buildings. More often than not, he’ll sketch a subject multiple times; occasionally, Ji collages together disparate sketches, then paints from those. In keeping with his unique style – informed by studies in both Eastern and Western art – Ji explains his process as “…translating everything into line and brushstroke. Though my work uses photography as source material like many Western painters, its very different because I’m not using light and dark shadow.”

Ji’s paintings, like his drawings, result from tireless preparation and intuition. “Sometimes, I’ll start with a vague idea, not knowing where I’m going, and slowly it will emerge what the painting is about,” he explains. This approach requires a concentration that the artist likens to walking a tightrope. Each careful step of the painting involves using calligraphy brushes to build up an area with layer after layer of paint, which is applied using brush strokes like the staccato ‘ax’ or curly ‘buffalo hair.’ Working on a table covered with felt for absorbency, Ji applies paint and sometimes washes it to reduce its intensity, giving the mulberry-paper background of his most labored-over pieces a weathered appearance.

That Ji’s recent paintings derive from images and notes he recorded as he witnessed the mass relocation effort is poignant, but also helpful in explaining the surreal, disjointed quality that these works sometimes possess. Buildings, people and plant life can appear to float on the painted page like objects bobbing on the water after a shipwreck, and a rock formation is as carefully rendered as a cluster of displaced villagers. The technique evokes the dreamlike way in which memory can function, or history is written, bringing certain details into clearer focus than others and telling stories that might otherwise remain submerged.