For ‘Time Out’ magazine

The women in Hilary Harkness’s paintings have never seemed like the sort that populate nurturing, feminist communes. But those depicted in the three new works that make up her second New York show are even less inviting. Now her slender and scantily clad stock characters inhabit exploitative class systems on a battleship and a whaling ship, and indulge their animal passions in an art-filled Alpine chalet.

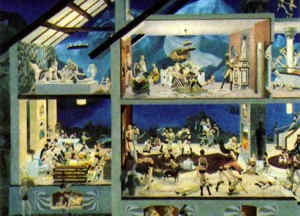

Violence and fear appear to be the factors that keep workers striving toward a collective goal in each dystopian scene. In Crossing the Equator (2003), scores of wounded crowd a battleship’s lifeboats. Details-a guillotine on deck, a bugle player who’s being executed by hanging-suggest that traitors are being flushed from the ship as it is evacuated. Heavy Cruisers (2004) is also set on a ship; the double entendre of the title alludes to both the vessel and the pregnant women onboard. In a lounge area, women view fetuses in jars, while next door, others occupy double-tiered stalls to give birth.

Harkness’s paintings seem determined to challenge stereotypes of women as peace-loving; coincidentally they’re on view at a time when the prison scandal in Iraq reminds us that female soldiers are as capable of abuse as men. Harkness takes this point to an extreme in Matterhorn (2003-4), in which debauched Fräuleins torture, fight and pleasure each other in a sadistic orgy of excess. Harkness may want to imply that sexual or social transgression is the ultimate expression of individuality. Instead, with their clone-like appearance, her women suggest an undifferentiated unit. Harkness’s paintings are a chilling vision of free will yoked in service to a higher power.