For ‘Flash Art’ magazine

“They’ve all gone on to do things in different ways and it doesn’t make sense to think of them as a group anymore. They never were. They just happened to be thrown together, with good reason.” – Vince Aletti, Village Voice photography critic

It was a scramble, but they did it. With only a few weeks to plan, new gallerist Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn and artist Gregory Crewdson dashed around New York City on marathon studio visits, quickly assembling work by thirteen artists from six countries for the second show at what was then called Lawrence Rubin Greenberg Van Doren Fine Art. Four years later, ‘Another Girl, Another Planet’ has become one of the most talked about photography exhibitions of the past decade. Critics have described it as “instantly historic,” the “it show” of the moment, establishing a movement of “it photography.” As the legend grew, the show became the art exhibition equivalent of Woodstock – everyone claimed to have knowledge of it, even if they hadn’t actually seen it. In fact, it so captured the imagination of the art world that the show became a symbol of a new movement, characterized by blurred boundaries between documentary and fiction photography. All but one of the artists were women, and the exhibition focused on photographs of women or girls, so it wasn’t long before the moniker ‘girl photographer’ started to stick. Most of the artists didn’t exclusively take pictures of young women, but in the ensuing buzz, that fact was often overlooked.

Despite their diverse backgrounds, those who became most closely associated with ‘Another Girl’ were Jenny Gage, Justine Kurland, Dana Hoey, Katy Grannan and Malerie Marder, the five women in the show who had graduated from Yale University, where Gregory Crewdson taught. By March 1999, when the exhibition opened, most had already embarked on promising careers, showing their work in galleries and contributing to news and fashion magazines. Although these factors made the moment ripe for a statement, “…there is no way to plan or strategize a show like that,” said Crewdson. “It’s so much about a moment and timing.” In fact, the timing was so right that artists who were not in the show began to be mentioned in the same context. A year after ‘Another Girl,’ Harper’s Bazaar ran a piece on the five women from Yale and Nikki S. Lee, who had studied at NYU but whose fashion background and self portraits exploring identity linked her to the others. In the same month, Deborah Mesa-Pelly, another Yale grad, who took photographs in elaborately staged domestic settings, had her first New York solo show and was quickly drawn into the fold by critics.

‘Another Girl,’ and the publicity surrounding it, may have been an incredible break for the artists, but it also presented them with problems. Most of the artists who were either in the show or associated with the kind of staged photography it represented were happy for the exposure but frustrated at the way they were assumed to be a group. For example, one of them could not have a show reviewed without mention of the other ‘girl photographers,’ a trend that is only now starting to abate. Their media debut also coincided with a number of splashy articles about various young, contemporary artists in magazines like Vogue and Vanity Fair, prompting New York Times critic Roberta Smith to brand the new generation the “B.Y.T’s: Beautiful Young Things.” Others, like photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia concluded that, while interesting, ‘Another Girl’s’, “…impact seemed to have more to do with the fashion of the moment and the necessity to create personalities for the newer and dumber versions of the art press than any confluence of artistic merit.

” Ironically, the subsequent success of each artist validated the attention paid to ‘Another Girl.’ “So many of those people have gone on to do interesting work,” explains Aletti. “If that hadn’t been the case, I think people wouldn’t be referring back to that show.” Since ‘Another Girl’ opened, critics had been acknowledging that the artwork was, to quote Katy Siegal’s Artforum review, “…a disparate collection of technique and intent.” But even years later, the artists found that their work wasn’t being considered entirely on its own merit, at least when exhibiting work in New York. “Showing in Europe gave me a chance to break away…The people reacted to the work on its own, not in relation to the other women’s work,” said Gage in an observation that echoed the other artists’ experience. Above all, the act of producing and showing their work is what continues to persuade art audiences to acknowledge each artist’s individuality. Last spring, Marder and Mesa-Pelly showed new work, and this fall, Kurland, Grannan and Lee all have solo exhibitions that reveal the extent to which they have found their own voices.

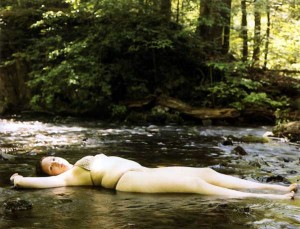

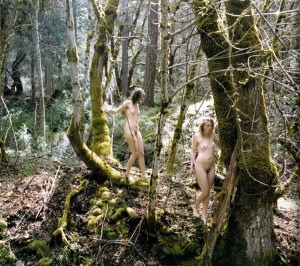

Perhaps more than the others, Kurland was associated with the ‘girl photographer’ phenomenon because, unlike Hoey and Grannan, for example, she actually did intensely focus on girl subjects who she photographed in landscapes. However, by her second New York solo show in Fall 2002 at Gorney Bravin & Lee, she began to focus on adult subjects in two new bodies of work set on communes and gardens across the United States. Most recently, Kurland presented ‘The Golden Dawn’ an exhibition of work completed in 2003 that opened in September at Emily Tsingou Gallery in London. Vast American landscapes dominate, almost swallowing up the often tiny male and female nudes that clamber over boulders or nearly disappear behind mossy trees. Here, nature isn’t so much a spiritual retreat as a setting for interacting with the divine, whether it’s a desert scene in which men, women, and children gather in a circle, or a quiet stream next to which a woman lies on her back as patterns are painted on her skin. In the past, Kurland has expressed interest in utopian ideals, and there is a strong sense here of mixed pre and post-lapsarian boundaries. Some characters, like a wide-eyed blond and her female companion move through the forest with a cautious innocence too young for their years, whereas in ‘The Fall,’ a nude man and woman descend a hill together, his posture recalling Adam’s in Masaccio’s ‘Expulsion from Eden.’

The landscape also figures in a new way in one of two series of photographs by Katy Grannan on show through the beginning of October at Artemis Greenberg Van Doren Gallery and at Salon 94 in New York. Around the time of ‘Another Girl,’ Grannan was making portraits of men and women in their suburban and rural homes, having met them through newspaper ads, referrals and direct contact. In the latest color series, ‘Sugar Camp Road,’ Grannan captures her subjects outdoors, in locations that have personal meaning for them. The title of the show, though it sounds innocuous, refers to the location for one of the last pictures made in the series and to the site of a brutal murder. Despite the setting, the sitters are the true focus of the pictures, even when they interact with nature. In an image titled, ‘Meghan, Saw Kill River, Annendale, NY’ a young woman lies in a shallow stream; goosebumps and beads of water are visible on her pale, almost bloated-looking body. Another scene shows an overweight young woman clasping her naked breasts while kneeling with her back to us in a pool of muddy water. Even without knowing that these are special spots for the models, it’s a mystery who they are or why they present themselves as they do. This lends them an exoticism that is compounded by the imperfections (and sometimes the oddities) of their bodies.

At Salon 94, Grannan showed ‘Morning Call’ a series of smaller black and white portraits made indoors. Opposed to the photographs taken outside, the sitters for the indoor pictures compete with riotous natural patterns on the wallpaper and furniture for the viewer’s attention. In one extreme and completely charming image, an adolescent boy and his little brother, wearing a combination of stripes and plaids, stand proudly before a wall papered with a bold, flying bird pattern. Grannan’s imaginative approach to portraiture plays with identity and location to fascinating effect.

By contrast, Mesa-Pelly obscures identity through location. In ‘Tilt’ a series of seven photographs shown last May at Sandroni Rey Gallery in L.A., the artist almost abandoned the human figure to concentrate on the strange happenings in her domestic interiors. Mesa-Pelly first received widespread attention for her photos of elaborate sets in which young women had just discovered a passage into another world. In ‘Tilt’ the theme of discovery is still strong, but this time, it’s the viewers who uncover the unexpected. The photographs are taken as if whoever is behind the camera has just rounded the corner and pulled up short at the sight of something strange. The effect is less spooky than magical but sometimes borders on the cheesy.

The best example of this is ‘Matterhorn,’ in which the camera peers into a bedroom through a half open door. On a pillowless bed sits a papermache mountain, a little white plastic tree and several Styrofoam spheres. The resulting image looks like a hybrid, low-budget attempt at staged landscape photography and is reminiscent of a few earlier photographs in which Mesa-Pelly deliberately exposed her ‘natural’ materials as man-made. It’s as if she is taking on ‘fakeness’ itself as her subject matter and forcing viewers to think about how easily they are led into the fantasies she concocts in other photographs. Two such examples are ‘Balustrade,’ in which seductively gloved hands pull a red rope over a wooden banister, and ‘Garland’ in which we peer up a narrow staircase through dozens of white paper or plastic chains.

It’s hard to pin down Mesa-Pelly’s subject matter, because the work is driven by the pursuit of wonder. Malerie Marder, on the other hand, has reduced her subject matter to its essence. Known for her nude images of friends and family, Marder captured the objects of her interest in their most vulnerable state for ‘At Rest,’ a video and portrait installation shown at Salon 94 last January and more recently at blackbox in Edinburgh, Scotland.

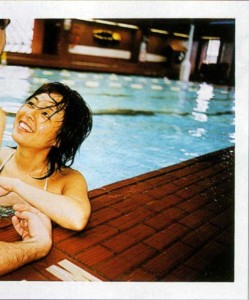

In her past work, Nikki S. Lee took on the role of actor in dramas of her own devising. Dressing the part of a skateboarder, elderly woman, or stripper, she asked friends to snap photos of her as she adopted the look and mannerisms of her chosen demographic group. In a body of work that will be shown in November at Leslie Tonkonow Artworks and Projects in New York, Lee has come closer to producing staged images by working closely with a photographer to predetermine the composition of her work. She is still the central character in the resulting images, but there is no longer an urge to scan the photo to ‘spot Nikki,’ because each image has been cropped to eliminate all but a trace of her companions. In most cases, the shots appear to be candid. Lee is looking away from the camera, absorbed in whatever is going on just outside the frame. In one garden scene, we see a man’s arm held protectively around Lee’s shoulder, and elsewhere Lee beams a smile upward toward a man at the side of a swimming pool. A flushed and happy Lee holds a baby in her arms as she sits up in a hospital room. Elsewhere, she sits in a car’s passenger seat with a broken arm as a man’s hand roughly grasps her breast. These scenarios reveal that Lee is still interest in role-play and identity, but she now challenges viewers to figure out where she is and what she’s doing.

Four years after what Crewdson calls, “…the show that people love to hate and hate to love,” the artists involved are prospering. Plans for an expanded, traveling version of ‘Another Girl’ were dropped soon after they were formulated, but since then, the artists have been invited to participate in group exhibitions which situated their work amongst male and non-Yale artists alike. Dana Hoey, who is working on a radically new body of work, has particularly benefited from imaginative efforts of curators who have recontextualized her work in group exhibitions. At Britain’s National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, curator Patrick Henry included work from Jenny Gage’s ‘Helen’ series in his exhibition ‘Fabula’ which, as he put it, “…moved on from the familiar ambiguities of staged photography to something more searching and sophisticated – something that sought urgently to re-engage with the real.” Gage, who often works in partnership with her photographer husband Tom Betterton, is releasing a book titled ‘Hotel Andromeda’ this month published by Artspace Books and accompanied by a text by writer Heidi Julavitz. In the course of a career, four years isn’t much, but it’s been enough for each artist to mark out her own territory and for us to realize that we’ll be watching them for a long time to come.