For ‘Art on Paper’ Magazine

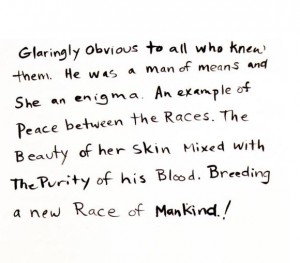

By the time Kara Walker’s first full scale American museum survey arrived at the Whitney Museum from the Walker Art Center last fall, a wave of press coverage, including feature articles in the New Yorker and Art in America, made it the must-see show of the season. But it was the fifty-two-panel, handwritten text in Walker’s simultaneous downtown gallery show that deserved the attention. Flanked by smaller works in her signature cut-paper style illustrating atrocities committed against freedmen after the Civil War, the enormous text installation, with an equally expansive title (Search for ideas supporting the Black man as a work of modern art/contemporary painting; a death without end, an an appreciation of the creative spirit of lynch mobs), stood out for its sheer unornamented rawness—no illustrations, just scribbled handwriting—and its scathing references to U.S. military action in the Middle East.

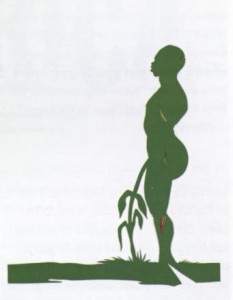

Since the mid-nineties, Walker’s silhouettes, paintings, videos, and projections have consistently conjured imagery of the Old South in abject yet clearly readable scenes of violence and sexual subjugation. When she used text, it was written in what could plausibly be the artist’s own perspective or that of an alter ego. Her more recent text-based work (since 2002) adopts a range of voices—anthropologist, slave, contemporary middle class African-American.

Search for Ideas is an even more cacophonous brew of observations and perspectives. Here, Walker explores the potential analogy between racist attitudes in America and those perpetuated by Americans overseas in texts that refer to Saddam Hussein as a “porch monkey” or Arabs as “sand niggers.” Under the rubric of aggressor and complicit victim, the text details rapes and torture, proffers that black soldiers are willing Klansmen and asks, in the face of global jihad, “how can colored folks get on the winning side w/o giving up their hard-won right to jeans that fit…” Because the fifty-four parts are hung cheek-to-jowl and there is no obvious sequencing, it is unclear whether one is supposed to read them left-to-right, or top-to-bottom.

Likewise, the show’s small cut-paper works and large-scale collages on panels lack clear storylines, such as ReConstruction (2007), a decorative mélange of floating silhouetted heads over a background of post-9/11 New York Times ads offering condolences.

From Richard Serra’s 2005 poster recreating a scene from Abu Ghraib to Jenny Holzer’s presentation of declassified documents pertaining to military bungles in Iraq, among many other examples, Walker is not alone in using her artistic platform to protest U.S. foreign policy. Yet Search for Ideas seems uniquely geared to offend and disturb by its graphic descriptions of violation, its willingness to lay blame all around, and its success at tapping another well of middle-class guilt, this time over atrocities committed in the name of the American public. A schizophrenic toggle between individuals and nations, and between first and third person, makes for a confusing and overwhelmingly despairing indictment. However, as a grating tour de force of ugly truth, the piece is powerfully effective and makes a loud riposte to one text’s assertion that “Knowledge comes in the form of whispers of those in the know.”