For ‘Flash Art’ Magazine

The story begins in the remote mountains of north Georgia. Four buddies from the city are canoeing down a river on a weekend trip when their back-to-nature bonding experience suddenly turns into a nightmare. Out of the blue, a couple of backwoodsmen hold two of the party at gunpoint and rape one of them. This is both the pivotal scene in the 1972 film ‘Deliverance’ and the inspiration for ‘Here Piggy, Piggy,’ a new sculpture by Gary Simmons. ‘Here, Piggy, Piggy’ is an all white, fiberglass replica of the two hillbillies but with a twist. Their overalls, grimy caps and appalling dental hygiene are the same, but they have been transformed into bobbleheads, with giant rotating heads and bodies shrunken to the size of a child’s.

Beautiful, haunting, poetic…These are some of the words that come to mind when looking at Simmons’ erasure drawings, which are the signature works he has created for over a decade. The artist makes them by drawing his subjects in white chalk on chalkboards or slate colored backgrounds, and then partially erasing the drawings, leaving incomplete figures and smeared traces of white chalk. On first viewing, the new sculpture, modeled on collectibles with nodding heads, seems to be a dramatic departure from the serious sensibilities of the artist’s earlier work. But on further consideration, the differences are not as great as they first seemed. In fact, the new work continues Simmons’ tradition of embarking on new projects while maintaining continuity with a steady series of erasure drawings. The drawings and the sculptural, photographic or video projects are symbiotic, mutually beneficial to each other by their elaboration on themes of memory, history and the presentation of cultural difference in pop culture.

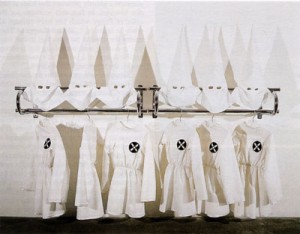

In the thirteen years since Simmons had his first solo show, he has moved from producing racially charged drawings, sculpture and installations to creating enigmatic wall drawings on a huge scale, accompanied by drawings on paper, linen and chalkboards. Simmons came of age in the late 80s and early 90s when multiculturalism was the art world buzzword and his child-sized Klu Klux Klan outfits, for example, were in keeping with the times. But by the mid-‘90s, his work experienced a shift that was emphasized in the artist’s first large-scale museum exhibition curated by Thelma Golden of The Studio Museum in Harlem (SMH). The catalogued show began in 2001 in Chicago, stopped at Santa Fe and ended this month at the SMH. Nearly thirty drawings, sculptures, photographs and videos from the past seven years were included, along with a major new sculpture (‘Here, Piggy, Piggy’) and a large site-specific wall drawing.

When his early drawings of popular cartoons that stereotyped African-Americans were first exhibited in Europe, Simmons soon discovered that much of his audience considered the work part of a uniquely American situation. Partly in response to this reaction, Simmons gradually changed the subject matter and style of his work in an attempt to address more universal issues. He explains that, “I wanted to open up the dialogue so it wasn’t as isolated to the African American experience. [I included] images of sites that we all interact with or come into contact with so that [in terms of] access to the work and the issues around the work, each person could import their own experience.”* Meanwhile, back in New York, Simmons’ other projects were also being perceived as specific to his experiences as a young African-American. Writing for the New York Times, critic Holland Cotter wrote that Simmons “…brings the language of black hip-hop into an art world that still doesn’t know what to do with it.” Reviewing the same show for Artforum, Jan Avgikos turned Cotter’s observation around to propose that the artist “…emphasizes the ‘outsider’ position of the institution in relation to Pop art…”

Faced with being pigeonholed as an artist whose work related only to a particular time and place, Simmons altered his style around the mid-90s. That change was the starting point of the museum survey. With the exception of ‘Flute Player,’ a drawing from 1995 in which a cartoon figure with a bone on his or her head plays the flute, the focus of the exhibition was entirely on work with no obvious racial or political content. There were drawings of staircases leading into the unknown, of city apartment buildings and shacks in the countryside, of roller coasters, pine trees and stars, but not a stereotyped cartoon drawing, pointed white hood or noose to be seen. Did Golden and Simmons team up to rewrite his history, editing out the artwork which links him to the multicultural art discourse which disappeared from view in the mid-90s?

‘Lost Ones,’ a site-specific drawing executed on an entire 40-foot long wall of the largest gallery helps answer this question. Near the center of a vast, slate colored background, two enigmatic bell-like shapes hang at angles to each other. Each has been partially erased by hand, and the clearly visible finger marks moving out towards the far wall create the impression that they are moving quickly towards each other. In fact, the shapes are bird cages, and the ‘Lost Ones’ the two birds that have flown away. The cages hint at confinement, emancipation and finally the violent crash of the mechanisms that held the birds captive. They also refer back to an installation from 1990, ‘Pollywanna’ in which Simmons placed a live, caged parrot in front of a drawing of two crows from the Dumbo cartoon. Observing the bird led the artist to experiment with an erasure technique. He explains that “…as you looked at the bird, it almost left trails in the wake of the movement of the wings…you see ghost images of the wings moving.” These chains of association run through all of Simmons work and are what link the bobbleheads to the birdcages.

In their own ways, ‘Lost Ones’ and ‘Here, Piggy, Piggy’ deal with power relations and the loss of self-governance. ‘Lost Ones’ does so allegorically, while ‘Piggy’ references violence from a popular film seen and remembered by a generation. At the beginning of the movie, the four adventurers make contact with two families living in extreme poverty and badly affected by inbreeding. These scenes set up a conflict between the city men and their country counterparts, between civilized and wildness, a dichotomy that is often premised by racial difference. In this case, both parties are white, but Simmons points out that “…the fears and stereotypes are all right there and inherent within the film. It’s about the fear of others.” The artist’s interest in the cultural ‘other’ led him to make work that investigates the culture of the southern U.S. As well as being the site of hundreds of years of racial violence, Simmons says of the South, “I think there is a lot of hidden imagery, language and culture that effects us day to day that is literally ghosted.” All of the artist’s erasure drawings summon a ghostly presence that hints at hidden histories. In fact, this accounts for the color of ‘Piggy’ which has been painted all white to, “…almost disappear. They mirror the spirit of the drawings in that way; you’re dealing with something that is recognizable to a point. Like the way your memory works, the edges are sanded down…”

Simmons’ erasure is neither a consequence of a particular working method, nor an aesthetic device. Instead, it has political overtones that are reinforced by the fact that no humans ever appear in the drawings. Some of the best pieces in the exhibition are from a 1996 series of roller coaster drawings titled ‘Ghoster.’ Sections of the coaster’s support structure are rendered as jagged beams, ending in spikes that communicate a menace beyond the scariness of the ride. As in ‘Piggy,’ the thrill seekers are in for more than they bargained, as they lose control in the presence of the, in this case supernatural, ‘other.’ In a major project from 2001, Simmons created a ‘haunted house’ by transforming the walls of an abandoned house in rural New Mexico. The dilapidated structure was not restored, nor were plans made to preserve the wall drawings. The partially erased drawings, their stories obscured by the form they take, mirror a ghost’s fleeting presence as they disappear over time.

Simmons also awakens his audience to the existence of the cultural ‘other’ by making erasure drawings of text that relates to the particular series on which he is working. In a series about drinking, Southern terms like ‘Moonshine’ or ‘Ruckus Juice’ appear in paintings with the same names. Drawings of wishing wells and stars are accompanied by different versions of the words ‘I wish,’ and his current series involves slang and words that refer to pot smoking. By abstracting terms that won’t be found in the dictionary, Simmons focuses attention on the way language is adapted by individuals and communities. The way the words are blurred mimics the way that meaning is obscured for someone from outside the community. For instance, if a viewer isn’t familiar with the reference in Simmons’ painting to Lauryn Hill’s song ‘Lost Ones,’ a shade of meaning is hidden. Simmons compares his work with a DJ’s sampling saying, “There will be references that will be picked up and then there are others that won’t be. That’s OK. When I put two images together and recontextualize them, they become something new anyway.” Simmons is careful to say that, “The viewer might question the fact that they’re on the outside, but they won’t feel like an outsider.” But unless the term ‘ruckus juice’ happens to be in the viewer’s common usage, he or she necessarily assumes the role of ‘outsider.’ Whereas Holland Cotter and Jan Avgikos pointed out in 1993 that the work positions the art world and the art institution on the ‘outside’ of art that references African-American culture, the text drawings, which reference slang terms from a variety of communities, unseat the viewer from an authoritative position.

Ironically, we spend much of our lives wishing to be what, who or where we are not. The precursor to ‘Piggy,’ and the artist’s first all white sculpture were replicas of the stills used to illegally manufacture liquor. Coincidently, the protagonists of ‘Deliverance’ first assume that they have aroused their opponents’ anger by stumbling on a whiskey still. In fact, stills symbolize the supposed lawlessness of deeply rural areas, beyond the arm of the law’s reach. At any rate, Simmons’ focus is the potential of these stills to meet the demand for cheap liquor and plenty of it. In an interview in 2001 with Franklin Sirmans (printed in the exhibition catalogue), Simmons explains that these sculptures are “…about a desire to be somewhere else.” In this respect, they relate to a series of drawings of stars, wishing wells and text drawings of the word ‘wish.’ Wishfulness and drunkenness are ways to escape or take a break from reality, to step into another life. In this respect, both also address what it is to imagine, in a sense, being ‘other.’ Like the birds in ‘Lost Ones,’ who have received or taken their freedom, viewers are left with a choice to fear or embrace their desires.

The four outsiders in ‘Deliverance’ ventured into unknown territory and suffered the consequences. The rules to which they were accustomed no longer applied, and they received no mercy at the hands of their armed captors who Simmons preserves in fiberglass. The Ghoster series also alerts viewers to powers beyond their control, because the appearance of the supernatural subverts even the laws of nature. Finally, by isolating words particular to a culture or geographic region, Simmons hints at the way in which otherness is embedded in the English language. The combined effect of this body of work is to reawaken viewers to the complexity of cross-cultural relations by destabilizing their own positions. Viewers will find themselves on one side or the other (or neither) of the distinction between North and South, and no single viewer will be familiar with all of the jargon that inspired the text drawings. Simmons work forces viewers to see themselves rooted in a particular experience, one of many.

*Unless otherwise noted, all quotes are from a conversation with the artist on November 19, 2002.